The Bighorn Crags are discussed on Pages 122-126 of the book and there is an access map on Page 143.

The Bighorn Crags form a distinctive, high-granite divide more than 20 miles in length which towers nearly 1,000 feet above the surrounding mountains. The Bighorn Crags offer many excellent challenges to mountaineers and a surprising amount of good rock to entice rock climbers. The quality of the Crags granite is much like Sawtooth granite: hard and clean in some places; soft and deteriorated in others. Many of the best walls and rock are found down in the canyons rather than on the peaks which, in some cases, are still covered by metamorphic overburden. Climbers who come to the Bighorn Crags should expect to find little in the way of company or conveniences such as established bolts for rappelling.

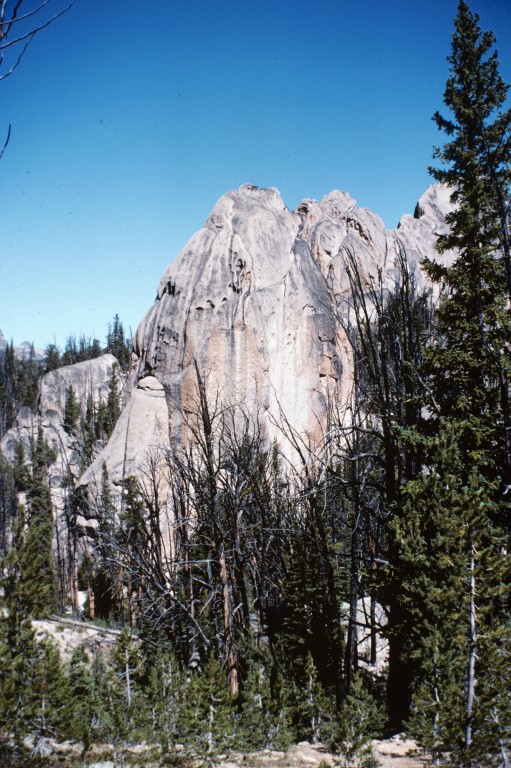

There are 3 major rock-climbing areas within the Crags. The first is the “Cathedral’s Cemetery,” which begins 2 miles from Crags Campground and occupies an area along the main trail for almost 2 miles to the base of Cathedral Rock. The domes and spires resemble giant tombstones. I have climbed Peak 9140 and Peak 9100 in this group. Cathedral Rock, of course, resembles a cathedral. The Cemetery includes 14 spires and domes, which vary considerably in size and shape and offer simple bouldering problems as well as more complicated one- and two-pitch route rock-climbing routes.

The second area of interest to rock climbers is a tangled collection of spires, faces, and cliffs at the west end of Ship Island Lake called the Litner Group. Because it is more than 10 miles from the nearest trailhead, little climbing activity has taken place in the Litner Group but, rest assured, the area has high potential for serious rock climbers. The final area is Fishfin Ridge with its high point unofficially called Knuckle Peak.

The Bighorn Crags from the summit Cathedral Rock.

Here is a bit of the Bighorn Crag’s climbing history (from the book):

While many mountaineers knew of the Selkirks and Sawtooths, few climbers had ventured beyond these spots. This changed in the mid-1950s when Lincoln Hales and Pete Schoening, two northwest-based mountaineers, discovered the Bighorn Crags in a remote corner of the Salmon River Mountains. Although Hales’ brief article in the 1955 edition of the Mountaineers Journal, titled “Climbing the Big Horn Crags of Idaho,” raised more questions than it answered, the pair were clearly the first to test the Crags’ granite.

Hales and Schoening made several first ascents, including their climb of shark-tooth-shaped, misnamed Knuckle Peak, the major climbing prize in the Crags. Hales’ article served as a stimulus for Idaho’s mountaineers to travel to the Crags. Beginning in 1957, a group of climbers centered in Idaho Falls formed the Idaho Alpine Club and adopted the Bighorn Crags as their climbing gym. These climbers, including Bill Echo, Dean Millsap, and Bob Hammer, knocked off all but one of the major rock formations that dot the Bighorn Crags and made many ascents throughout Eastern Idaho.

Unfortunately, the Idaho Falls climbers did not leave a written record of their exploits. The area is crossed by a good trail system, but it is a long drive from everywhere to reach the main trailhead. Below are a few photos mostly snowing the Cemetery area and Fishfin Ridge. Check out the peak listing for additional photos.

The long dormant Litner Group was finally visited a second time by a serious group of climbers led by Jim Pace in 2020. This group was comprised of Brady Johnson, Ian Cavenaugh, Max Bechdel, Jim Pace, Carolyn Pace, Cody Goldberg and Jeff Halligan. Read about there climbing exploits at the following link: Ship Island Climbing 2020 by Jim Pace

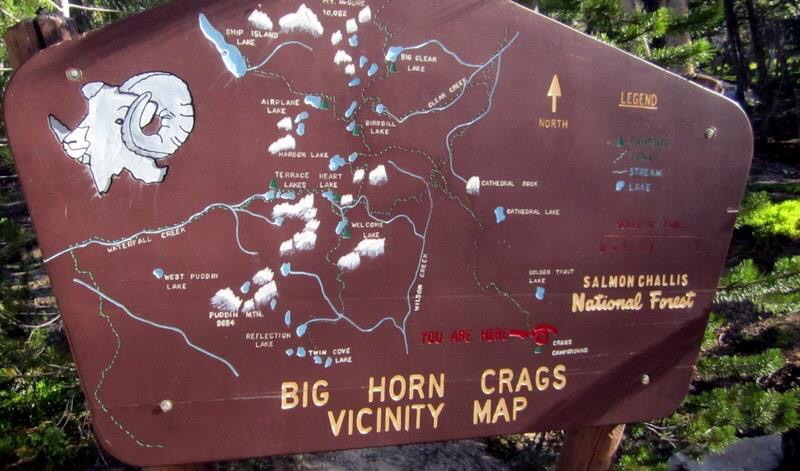

The sign at the trailheads shows the Crags’ trail system. Deb Rose Photo

The edge of Knuckle Peak and the Rusty Nail on the left and fishfin ridge tailing off to the right from the south end of Harbor Lake.

Knuckle Peak and Harbor Lake from the slopes of Ramskull Peak.

Hard Granite in the Cemetery.

View from the Cemetary to unnamed tower. Knuckle Peak and the fishfin ridge are on the right.

Good granite in the Cemetery.

An unnamed toombstone.

Another Toombstone.

Airplane and Ship Island Lakes with the Litner Group at the far end of Ship Island Lake. Bruce Reichert Photo

The seldom visited Litner group of towers viewed from the pass west of Ship Island Lake.

Fishfin Ridge viewed from the switchbacks leading to Birdbill Lake.

The Rust Nail from Harbor Lake.

Another view of the Rusty Nail. I believe it has been climbed but I haver no idea by who or when.

Another Toombstone. identified as Peak 9140 by list of John. Paul Bellamy, Dana Hansen and I climbed this formation in 1984. As I recall it was on pitch of roughly 5.4 climbing.

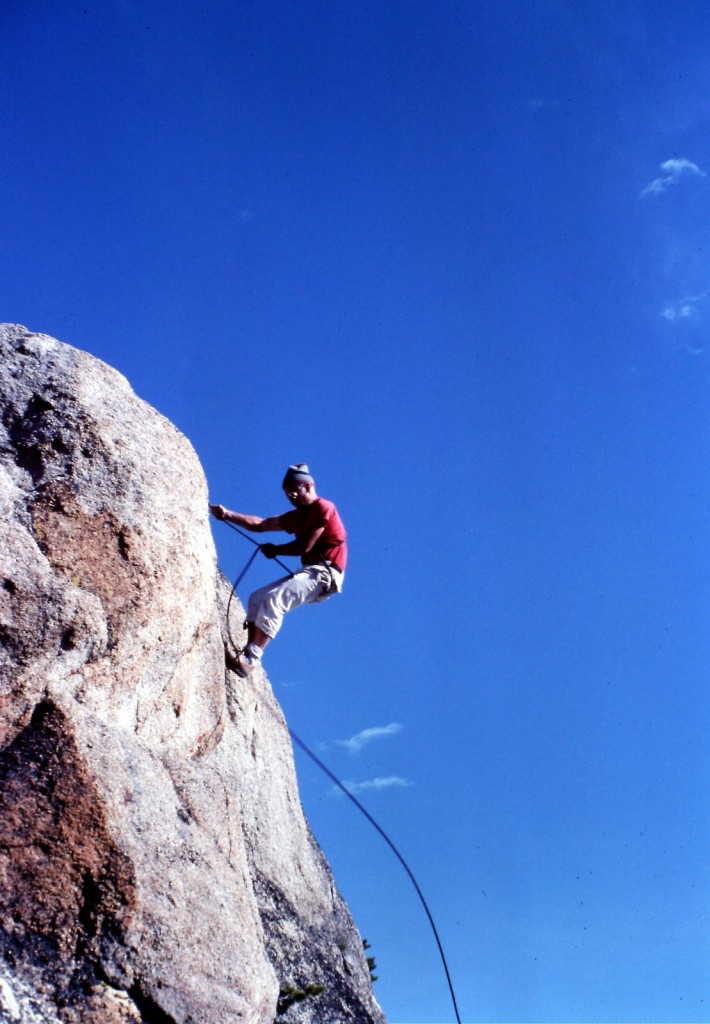

Paul Belamy rappelling off of Peak 9140 in 1984.

Terrace Lakes viewed from the east. The Middle Fork Salmon River is roughly 5,000 feet down this canyon.

Mountain Range: Eastern Salmon River Mountains