Note from the Editor: This wonderful article, provided for the Climbing History Section of the website, includes information that can be used to plan an ascent of Mount Borah’s East Face Dye-Boyer Route. As such, we have also included it as part of the Online Borah Climbing Guide.

Idaho – A Climbing Guide identified a route on the East Face of Mount Borah with a brief description of a climb that had been done in 1962 by Lyman Dye and Wayne Boyer, two pioneers of Idaho mountaineering. It read:

“East Face (II, 5.2). Climb the face from the notch on the Northeast Ridge (between the summit and Point 12247). Climb to the notch from Rock Creek, which is just to the north. The crux of the climb is the first 90-foot pitch out of the notch. The angle decreases and the holds improve above this pitch. First ascent: L. Dye, W. Boyer in 1962”

For decades, I assumed that Dye and Boyer had gone up Rock Creek (the standard approach to the North Face) to reach Point 12247 and from there climbed the Northeast Ridge to the summit. While the Northeast Ridge does provide a great view of the upper East Face and there is a traverse that cuts across the face, it leads directly to the summit, so I never understood how they could call their route the “East Face.” After reading the above description dozen of times and closely studying a topo, I realized that they must have gone up Rock Creek on the Pahsimeroi (east) side of the range.

Rock Creek leads to the upper East Face, one drainage north of the East Face Cirque where we had climbed in 2011 and 2012. Everything seemed clear to me now except for one detail and that was how they got to the notch between Point 12247 and the summit.

Being more than curious at this point, I contacted Tom Lopez to see if he had any more information about this route. Unfortunately he had none, but he did tell me that Lyman was still alive and living in Idaho. Using this lead, I was able to get in contact with Lyman and he most graciously provided me with all of the pictures and information for this route page. He also told me that he last climbed Mount Borah in 2013, at the age of 80, but that would be his last trip due to his doctor’s orders.

I was greatly honored that Lyman would share this little slice of Idaho’s early mountaineering history and am using his description and photos for the route information. Lyman perfected his discussion of the route with a bit of his early climbing history relating to his pioneering climbs in eastern Idaho and of the EE-DA-HOW Mountaineers. He writes:

“I started climbing Borah in 1957, done it in Winter and helped with search for Guy Campbell and Vaughn Howard when they went missing after an attempt after Thanksgiving one year. Those were some of the most horrendous conditions I have ever seen on the mountain. Art Barnes and Wayne Boyer were with me on just about all of the climbs in the Little and Big Lost Rivers and the White Clouds. We had a climbing group called the EE-DA-HOW Mountaineers. Wayne, his sons and I were on Mount Borah a year ago (i.e., 2013) in August when I was 80. It had been 57 years ago we climbed it together for the first time. Doctor says no more high elevations for me, sadly enough. We have been on it in almost every condition you can imagine. Winter, Spring, Summer and Fall. Not many areas on the mountain I haven’t been on at least once. When I lived in Arco, Mount Borah or King Mountains were the conditioning climbs when each climbing season began in the Spring.”

Lyman’s 2014 narrative continues:

If you will look at the pictures I sent you together as a group, at the very first mailing to you. The first picture had the Mount Borah East Buttress and the ridge coming off to the left. There is an angular ascending snowfield up to the ridge out of the canyon. That is where we gained the ridge crest and dropped over the East Ridge then contoured over to the big lower snowfield at the base of the face.”

Lyman’s narrative concludes:

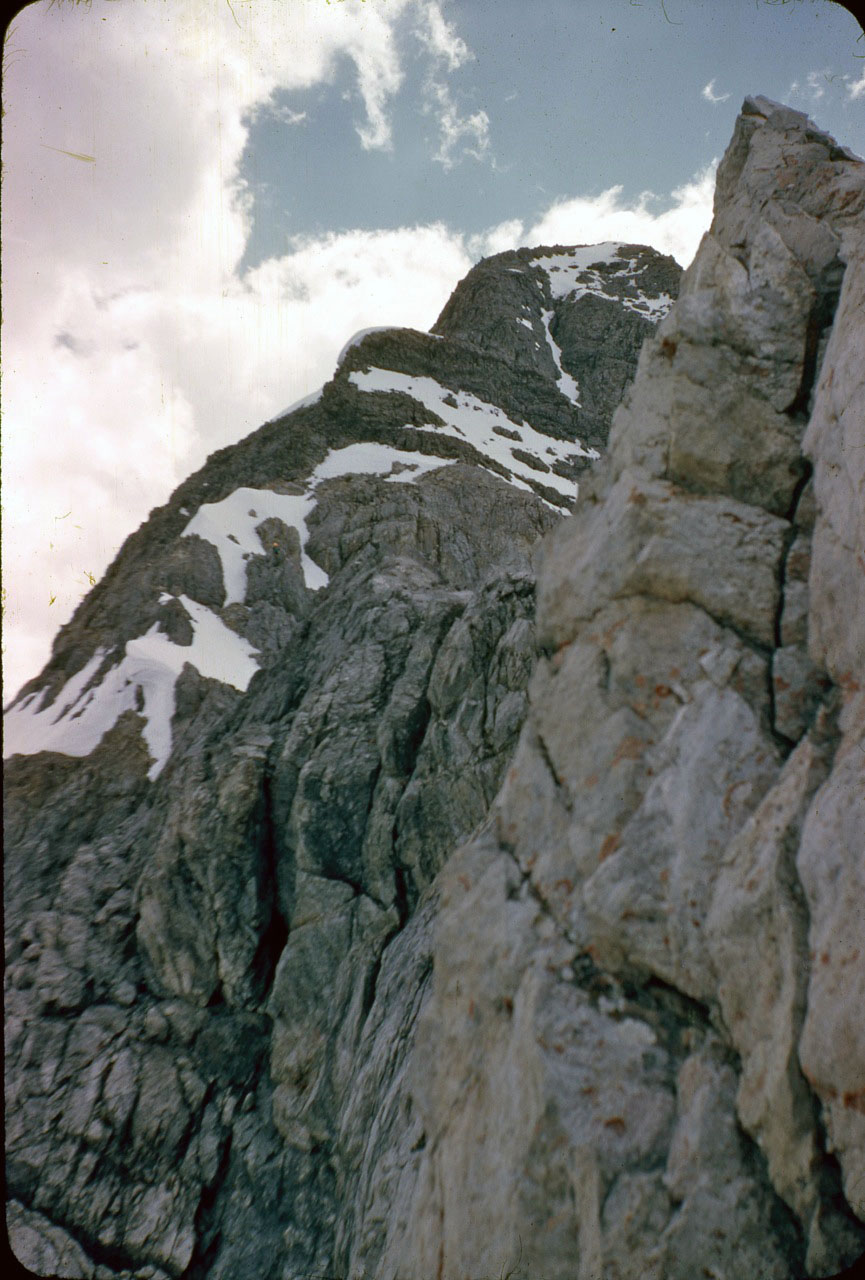

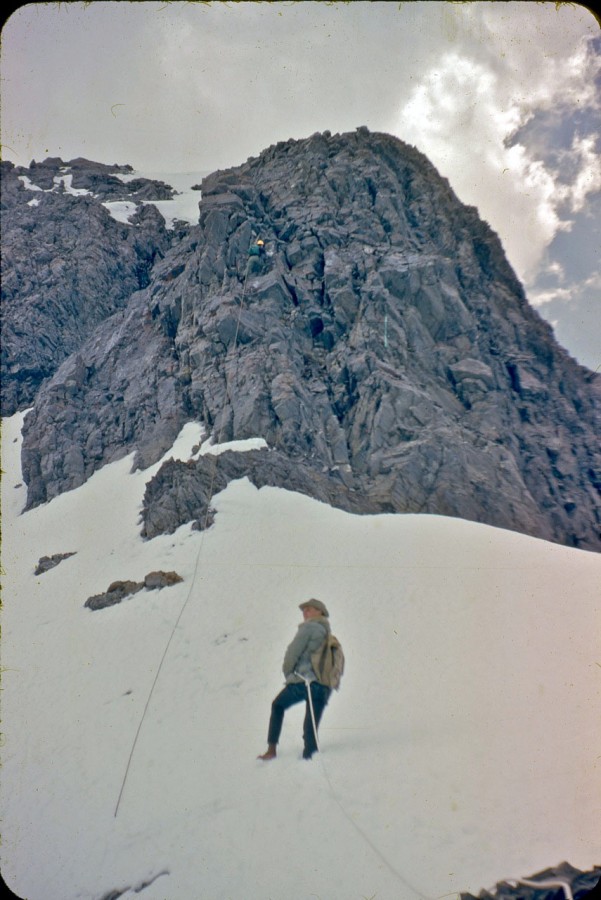

“If you will look at the second picture in the group of pics I sent you, there is a pic of me in profile near the East Buttress. To the left of my shoulder, you will see two snow fingers protruding upward to the right like tepees. The second one of those has a small snow patch up in the couloir above and to the right. We went up the rock face above that little patch, in and out of the crack, on the left side up to the thin snow finger, that ascends upward to the right, at the head of the finger to the right. At that point, we left the snow and climbed up the cliff formation past the black rock outcropping to the upper snow field.

There are two exit cracks that go up to the Northeast Ridge about halfway across the snowfield. I weighed taking one of those to the summit ridge but we had been out on that face for around three hours and we decided to go to the saddle and relax for a few minutes and have something to eat. I looked over the cliff formation and didn’t think it looked all that bad, and I put all my hardware in my pack and started up the cliff. I got about 40 feet up and got hung up under a little shelf. I could feel a crack with the tips of my fingers and would like to have had a piton or something to jam down in it for leverage, but everything was tucked away in my pack. I thought about down climbing and trying a different angle but didn’t like that feeling either. My legs were doing the piano dance by this time and so I figured I was probably going to peal out of there and fall or make a lunge for the crack and go for it.”

“The rest of the way to the summit was uneventful, a breeze so to speak. We dropped off the summit to the south to the first notch, and then set up rappels to get back down off the face. If I had paid more attention to the picture of me with the buttress, I would have seen the route sooner I think. The snow in your picture of the face (2012) is not anywhere as definitive as it is in the second picture. We had bigger snowfields when we did it than when you were up there.”

Lyman provided these additional photos taken during the first ascent of the Dye-Boyer Route on the East Face.

Looking up the route. Wayne Boyer is barely visible on the right side of this photo. Lyman Dye Photo

Looking down the col into the East Face Cirque. This is where the East Face Route joins the Northeast Ridge. Lyman Dye Photo

Looking across the East Face (left-to-right) at the Northeast Ridge, the col and what we call the “Super Buttress.” Lyman Dye Photo

Looking across the East Face (left-to-right) at the Northeast Ridge, the col and what we call the “Super Buttress.” Lyman Dye Photo