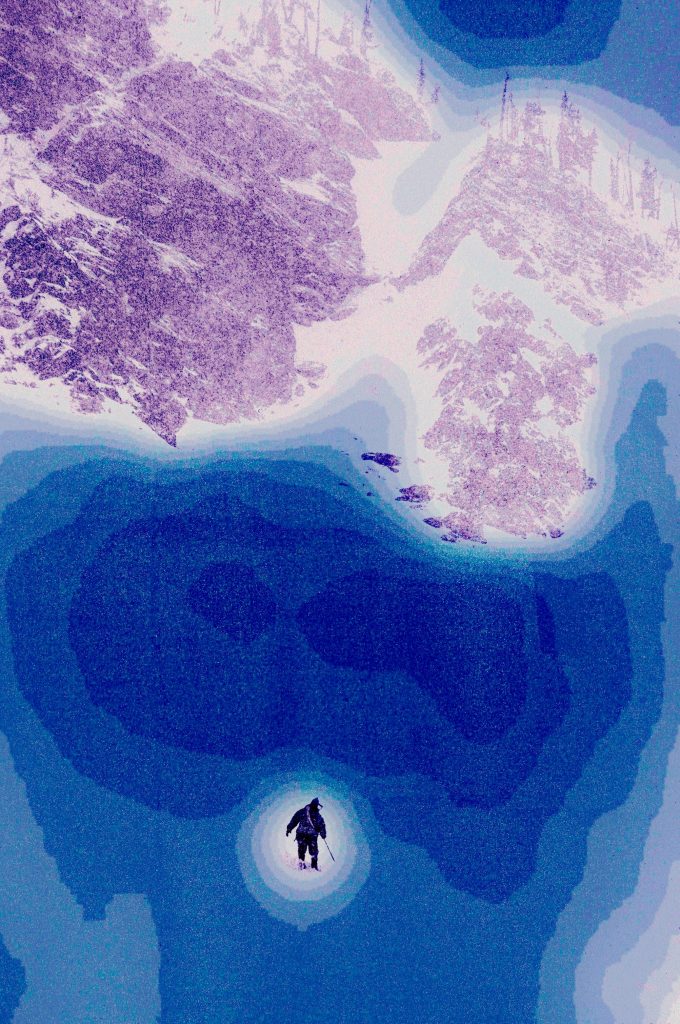

Who knows

what

God

might do to

awaken you.

Joe Leonard Photo

I found it exhilarating being roped to a companion while on the smooth, steep face of a mountain, making decisions to avoid physical harm or even death. The adrenaline rush cleared my mind of triviality and replaced within me a deeper sense of awareness. I loved the thrill of the challenge, of overcoming fear and of the precision required. No mistakes allowed. The euphoria is impossible to describe–there are no words.

When I was climbing, I was aware that my physical body functioned much better when the 3 attributes that I had been studying—the physical, mental and spiritual—were working together in harmony. It was another of Paramahansa’s gifts and I worked at making this awareness part of my reality, carrying his words with me on every mountain that I climbed.

The wind had been blowing at gale force all night as if to warn of things to come. We didn’t sleep at all and the tent was blown on its side, flattened by the gusting wind, constantly abusing us with body slaps and popping noises.

It was New Year’s Eve Day 1966 and we were on Mount Shasta, a major mountain with an elevation of 14,179 feet. The mountain rises 11,500 feet from its base. I was accompanied by 3 Sierra Club members with whom I had been climbing for almost a year. This was to be my first Winter ascent. Our goal was to spend New Year’s Eve night on the summit and to descend the mountain on the first day of the New Year.

My rope-mate was Jim Bacus. The other2 climbers were Bill Simpson and Reggie Donatelli. Reggie had been my climbing mentor since I met him. We had climbed Lover’s Leap in California and Echo Nine in Yosemite Park. These were my only serious climbing experiences prior to this attempt on Mount Shasta. I had learned the importance of well-chosen climbing partners and I was glad to be with accomplished climbers on Mount Shasta on whom I could rely and learn so much from.

Joe Leonard Photo

As I packed for the trip, I recalled everything that I had learned from my previous climbs and short apprenticeship. Mistakes had been made that I didn’t want to make again, so I packed with extra care. On one occasion in late Spring, Reggie and I were climbing a small peak in Yosemite named Echo Nine and were hit by an unexpected snow storm that came from the back side of the mountain. We were only halfway to the summit when it struck and were inadequately prepared. We had packed no cold weather gear and, most importantly, no gloves.

It didn’t take long to lose the feeling in our fingers. They were so numb from the cold that we couldn’t feel the small nubbins and cracks in the rocks. We couldn’t go on. Facing the possibility of frostbite, we drove a piton into a crack in the face of the wall, tied ourselves to it and attempted to warm our hands in the pits of our arms. The storm continued on, wind and snow blinding us as we hung on the side of the mountain. Any hope we had that the storm might pass was dimmed by the darkness of the storm. It was not abating and we were getting colder by the minute.

Reggie (always one to think of immediate options in times of crisis) said “Joe, let’s take our boots and socks off and use our socks for gloves.” His idea, as had been so many others, was brilliant. We struggled to remove our boots and socks. It was difficult to put our boots back on again with our frozen fingers, but working together we managed to do it without dropping them down the face of the mountain. The socks were just enough to keep our hands warm and we were once again climbing to the summit.

We finally reached the summit and sat in silence, each feeling a sense of accomplishment and watched the storm blow in its fury. It ended just as fast as it had begun. The sun broke through the clouds and warmed the mountain for our descent. It was a lesson that I would learn more than once on later climbing trips: Never venture forth on any climbing or backcountry trip, no matter the difficulty, without proper equipment. Always prepare for whatever possibility might be encountered in the wilderness. Someone has wisely said, “Good judgment comes from experience and experience comes from bad judgment.”

My climbing partners on Mount Shasta were, beyond everything, good company. The night before our ascent, in the comfort of the Sierra Club Cabin nestled in the trees at the base of the mountain, they told frightening stories–stories that they had heard from other climbers and folks down below. That it was an active volcano and overdue for an eruption, a sleeping giant. They talked about rumors of a vast colony of Martians living in its core who reached out from hidden doors to snatch unwary climbers. We all laughed at the tales but in the deep of night, thinking about climbing this mountain in the dead of Winter, the stories seemed to take on an unnerving reality and my sleep was tinged with disquiet.

We began the climb at dawn pushing our way through the strong winds and accomplishing our set goal, that of reaching the halfway point on the mountain on the first day. We pitched our tents amidst the ice and rocks on the only flat spot that the mountain offered us. The wind was blowing hard and it was almost impossible to anchor the tent to the ice and rock. As soon as it was secured to the ice Backus and I scrambled in hoping our bodies would stabilize the tent. The mountain was using the wind as its instrument and our tent as a weapon to slap and beat us throughout the night, making sleep hopeless.

Jim and I emerged from our shredded tent the next morning with our ears ringing from the pandemonium of the screaming storm. The sun was blinking in and out of the clouds as we ate a small meal of dried fruit and oatmeal, warming ourselves with a cup of tea. Thankfully the storm was passing on and visibility was excellent. It was a perfect day for a Winter climb. We had separated into 2 teams: Reggie and Simpson in one, Jim and I in the other. Reggie and Simpson had left camp before first light taking a different route than we would take. Jim and I had chosen a route that we were comfortable with—a couloir intersecting a ridge that led to the summit.

We set off alone. Not wanting to lose altitude, we slowly traversed the mountain meeting the couloir at a point where its slope ranged from 30-40 degrees, getting steeper as it rose up towards the ridge. The run-out at the base of the couloir was very wide and had narrowed considerably at the point of our interception. From here, we would climb up the face of the couloir for about 500 feet, meeting the ridge that would take us to the summit. The run-out below us was not steep but very long, broadening out well before it reached treeline.

The slope that we chose to climb to the ridge was not dangerous, so roping up wouldn’t be necessary. We would ascend without protection. It would, however, be necessary to cut steps in the wind-swept ice slope with our ice axes. We began our climb agreeing to leap-frog at 15-minute intervals. I opted to take the first lead. Cutting steps was not difficult and I was making good time up the face. Jim followed shortly behind and took over. As he continued onward, I cut a notch in the slope a few feet away from our snow ladder and sat down to take a few pictures and enjoy the view. A wide panorama stretched out before me: snow, bare rocks, forests and distant mountains. High above me the clouds made fantastical formations. I was witnessing the grandeur of God and I and my camera took what advantage of it that we could.

Joe Leonard Photo

I was so absorbed in the scenery that I had lost track of time and I suddenly realized that it was past time to relieve Jim of the tedious task of cutting steps into the icy slope. I stood from my perch and stepped into the steps Jim had carved out and looked up the steep ice field above to see how far Jim had gotten. I was stunned and confused. I could see nothing but white upon white. Where was Jim? I stared dumbly above me, closed my eyes, shook my head and looked again, but nothing had changed. Jim was gone!

My eyes scoured the slope. I looked down the face in panic, thinking he must have fallen and slid by me somehow without my noticing. There was nothing. The snow covered run-out was stark, void of all but a few large rocks. Farther on I could only see the never-ending forest that surrounds Mount Shasta. I looked up again, searching the face above me. It was open, bare, white, steep and empty. I thought perhaps he had managed to climb to the top but that was impossible. It was at least 300 feet to the top of the ridge. Even if he had quit cutting steps and sprinted, he wouldn’t be close to reaching it.

I was having a hard time overcoming my fear. It was just not possible that he had disappeared. There was no rational explanation, save one, that I thought upon as my blood ran cold: The stories were true. Jim Bacus had been abducted, taken into the mountain by Martians.

I looked back down the mountain, making certain that I had not missed anything, but Jim was nowhere to be seen. I was completely alone. A haunting fear arose as I experienced the awful feeling of utter desolation. The stories of the Martians entered my mind once more but I rapidly dispensed with them. I was confronted with a question even more perplexing than that posed by the inexplicable disappearance of my climbing partner: What should I do now?

My survival instincts rebelled against the notion of moving on up the mountain but how could I go back? What would I say to Reggie and Bill? Telling them that Jim had been taken by the Martians was starting to sound crazy even to me. If indeed Jim had somehow continued climbing up the mountain and something had happened to him, there might be the chance that he needed me. There was only one course of action I could justify and that was to follow him wherever he had gone.

Cautiously, I started up the steps that Jim had cut, looking left and right for any sign of disturbed ice or snow. It hadn’t taken long to reach the point where the steps he had cut ended. Once again I looked up. There was no hole, no door, no crampon tracks scrambling up the face and no opening into the inner recesses of the mountain. I had a fleeting, insane thought that perhaps the Martians had covered their entrance with snow, disguising it as part of the mountain. I imagined the snow exploding as Martians, with horrible eyes and drooling lips, burst forth, snatching me down into their cave. I wondered if my mind had lost its balance and laughed nervously at my imagination.

Thus I arrived at the last step Jim had cut and once again was faced with the question of what to do next. Do I continue alone to the summit and try to explain what happened, tell Reggie and Bill the impossible story that Jim was missing? Tell them he hadn’t fallen off the mountain and there was no sign that he had been dragged into the mountain? He had mysteriously disappeared into thin air. No one would believe that tale. I couldn’t believe it myself.

I wasn’t confident or experienced enough in my climbing abilities to consider a solo climb to the summit. Should I turn around and retreat to the Sierra Club Cabin at the base of the mountain and wait for Reggie and Bill to return? No, that was unacceptable. To turn back now, without having discovered the fate of my climbing mate, would be unforgivable. I had no choice but to continue onward.

I stepped into the last step that Jim had cut and, with a prayer, I lifted my ax to cut the next step. Just as I started to swing the ax and as in a dream, I was lifted off the snow. For one horrified, disoriented moment I flailed uselessly, terrifying thoughts racing through my mind: Martians. Falling. I am going to die. But nothing had a hold of me and I wasn’t falling down, I was falling up!

The wind had lifted me off the face of the mountain and I was flying up the slope and gaining speed, flying as fast as a rocket blasting off. I struggled to keep my body upright, reaching out helplessly with my ice ax and crampons to regain the mountain face. The wind was propelling me to the top of the ridge and as I careened up the face of the mountain, I wondered how high the wind would carry me and where would it drop me. With that thought, I panicked and struck out desperately with my ice ax against the mountain attempting to slow myself down but the wind was stronger than my futile attempts. I could see the ridge coming rapidly and felt utterly helpless, then grateful when I didn’t continued skyward. The wind hurtled me, light as a feather, over its ledge.

Ahead I could see jagged rocks jutting out from the ice like gargantuan teeth. Throughout all the wind and constant jarring, I was able to keep hold of my ice ax and I continued driving the point into the frozen ice below me. I was unable to drive it completely into the ice but I had managed to slow down the speed of my body as it slid over the ridge. I struck a field of rocks, bouncing off them dazed but unharmed. I was heading towards another barrier of rock spires and grabbed out for one but was unable to hold on. The wind was relentless as I careened through the rocks. I made one last attempt (successfully) to wrap my arms around one of the spires.

I was bouncing around like a sheet in the wind, clinging to my last anchor and was slowly losing my grip. I looked over my shoulder and all I could see was blowing snow–a total void. I had no idea what awaited me on the other side of the ridge which looked to be only 10-15 feet away. It took everything I had in me to keep a hold on the rock. I could only pray that I could outlast the gale but I felt my grip slipping as the wind slowly pried me loose from my lone salvation. Like it or not, I was going to find out what awaited me on the other side of the ridge.

Amidst the chaos and tumult of howling winds, blinding and stinging snow and overwhelming confusion, I was coherent enough to realize that I had to go over the ridge feet first and face the inevitable head on. It would be my only chance of surviving. As I let go of the rock, I flipped myself over on my butt and let the wind carry me into nothingness.

Airborne again, I felt the wind loosen its grip and drop me, like a stone, over the ledge into the unknown. I was no longer flying but falling with the blown ice and snow. I looked between my legs and saw below me a huge white ledge of snow and on the edge of it was my rope-mate Jim sitting alone amidst the white. I landed hard beside him and the snow gave way under me like a huge feather mattress. I sank up to my armpits and for the first moment in what seemed a long, long time, I was no longer moving. Everything was peaceful–infinitely quiet. I sat stunned and was unable to speak amidst the sudden silence. My mind was grappling with confusion, latent panic and blessed gratitude.

So we sat, Jim and I, motionless in unending quiet when suddenly I heard Jim’s voice break through the wall of timelessness around me. “What took you so long, Joe?” Jim was a man of few words. If we had landed anywhere but in that small snow deposit, we would have fallen to our deaths, one of those ’once in a lifetime’ events that sets one to think. I have been told (and I believe) that nothing happens by chance.

Joe Leonard Photo