The Wind River Mountains cover a large section of the Continental Divide running southeast from Yellowstone National Park to South Pass of Oregon Trail fame. The range is filled with beautiful granite peaks, spectacular lakes, flowers and a multitude of challenging climbing routes. My love affair with the Wind Rivers began on my first visit in 1981 during a backpacking trip to the headwaters of the Green River. During the trip, I discovered that the range had a lot in common with my first love (California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains) but also had a distinct Rocky Mountain flavor. Geologically, the backbone of the range is granite. Climate-wise, the range is pure Northern Rockies. Thus, the two ranges are paternal twins, not identical twins.

The Wind River Mountains cover a large section of the Continental Divide running southeast from Yellowstone National Park to South Pass of Oregon Trail fame. The range is filled with beautiful granite peaks, spectacular lakes, flowers and a multitude of challenging climbing routes. My love affair with the Wind Rivers began on my first visit in 1981 during a backpacking trip to the headwaters of the Green River. During the trip, I discovered that the range had a lot in common with my first love (California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains) but also had a distinct Rocky Mountain flavor. Geologically, the backbone of the range is granite. Climate-wise, the range is pure Northern Rockies. Thus, the two ranges are paternal twins, not identical twins.

The impetus for this trip was my desire to climb the 3 highest peaks in Wyoming. I had climbed the Grand Teton (the 2nd-highest peak) in 1981. Based on my study of guidebooks by Finis Mitchel (Wind River Trails), Joe Kelsey (Climbing and Hiking in the Wind River Mountains) and Orrin and Lorraine Bonney (Field Book: The Wind River Range), I knew that the other 2 peaks were located deep in the heart of the Wind River Range. I also learned that Titcomb Basin, one of the premier high mountain basins in the world, was the perfect base camp for Gannett Peak (the highest summit) and Fremont Peak (the 3rd-highest peak).

Photos of Titcomb Basin are enough to propel most mountaineers to make the long trek into this mountain Shangri-La. So I recruited Dana Hanson, my sister Sandy and her friend Charles, to spend a week backpacking in the range. We met in Pinedale, Wyoming and on August 7th, we started our hike from Elkhart Park, one of the highest trailheads in the range. The trail has lots of ups and downs and weaves around a bit on the way to Island Lake and then Titcomb Basin. On Day 1, we hiked to Seneca Lake in 9 miles.

The view from the trailhead.

Break time

Break time

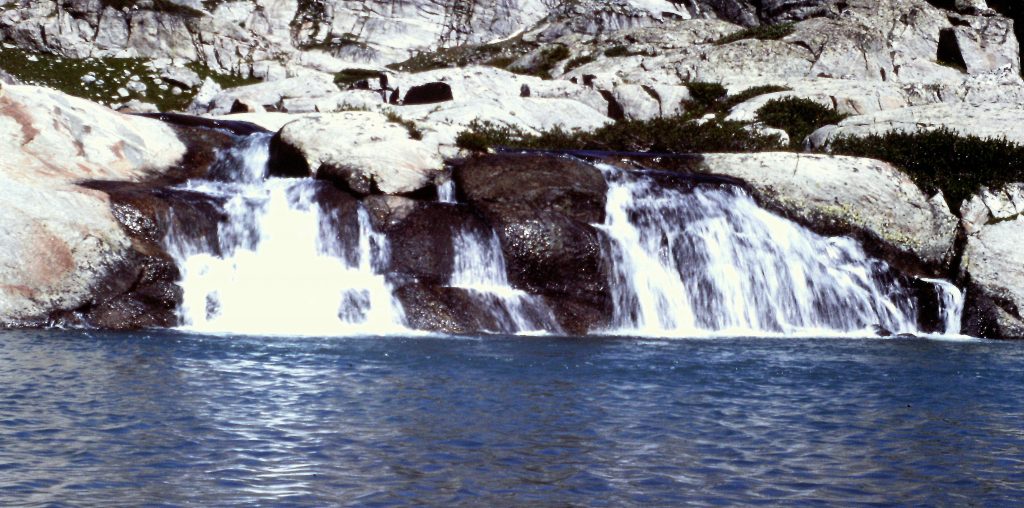

The next day, we hiked the final 6 miles to Titcomb Basin which covers a huge expanse of ground and includes the 3 large Titcomb Lakes. We were able to find an excellent campsite 200 vertical feet above and east of the middle Titcomb Lake. We had a great view, running water and privacy. We stayed in this campsite for 5 nights.

Island Lake and Fremont Peak.

Island Lake

Approaching Titcomb Basin.

The first Titcomb Lake.

Titcomb Basin

Looking across Titcomb Lakes toward Dinwoody Pass.

Titcomb Basin

On our 3rd day, we hiked to Indian Basin which was the next drainage to our southeast and back roughly 6 miles. Indian Basin was devoid of people and was nearly as scenic as Titcomb Basin.

Sandy and Charles returning from Indian Basin.

Elephant Head

Mistake Lake

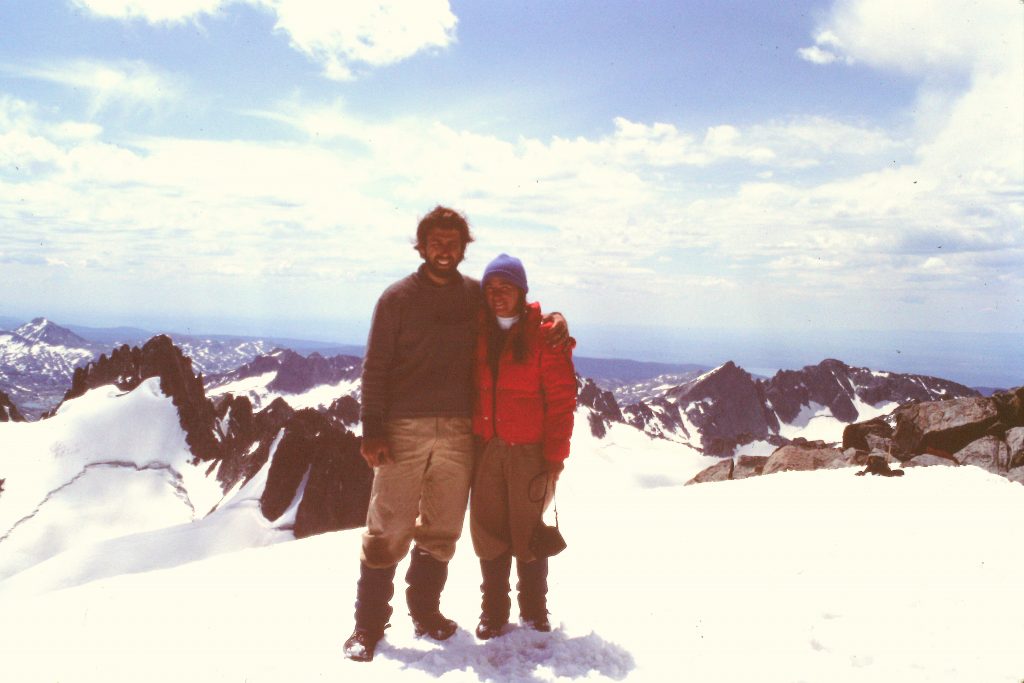

On the 4th day, Dana and I climbed Fremont Peak (13,745 feet). The peak was named after John C. Fremont. Fremont climbed the peak in 1842, thinking he was climbing the tallest peak in the Rocky Mountains. We climbed the peak by its broken Class 3 Southwest Face. To reach the peak (which was due east of our camp), we had to cross a low ridge that divides Titcomb Basin from Indian Basin and then cross the basin to the base of the peak. The route was steep, with a lot of large broken blocks, but even in 1982 it was marked by cairns. We encountered at least a dozen other climbers while we were on the mountain.

Fremont Peak. Our route ascended the rib to the left of the snowbank just right of center.

Titcomb Basin as viewed from Fremont Peak.

The Fremont Glacier as viewed from Fremont Peak.

On the summit of Fremont Peak.

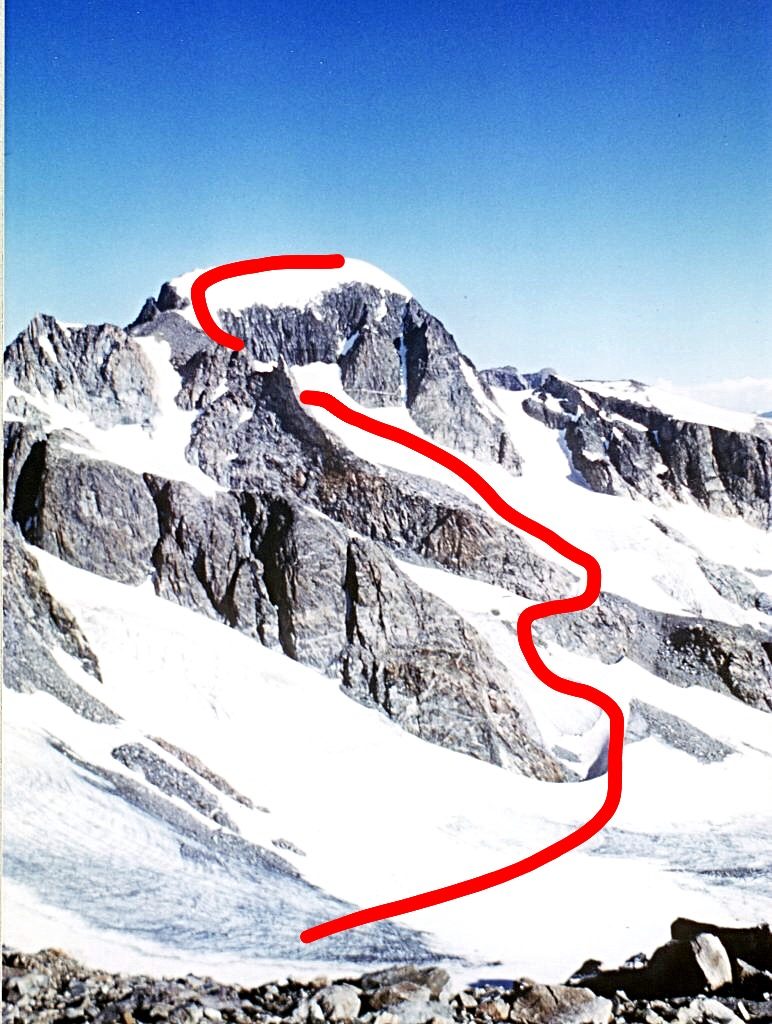

On the 5th day, we climbed Gannett Peak (13,804 feet) via the Gooseneck Route. Reaching the peak from Titcomb Basin involves a long, up-and-down climb, glacier travel and potentially technical obstacles on Gooseneck Ridge. Our approach trek took us up over Dinwoody Pass (12,800 feet). The South Side of the pass is steep and it was icy. We had to use our crampons and ice axes. From the pass, we descended more moderate slopes to the Dinwoody Glacier and then traversed across the Dinwoody losing more elevation to the spot where it intersects the Gooseneck Glacier.

The climbing starts at this point. The route climbs up the Gooseneck Glacier to a point where you are north and west of the Gooseneck (a pinnacle on Gooseneck Ridge). We were fortunate, as the condition of the bergschrund was such that we found a relatively easy crossing west of the Gooseneck. The bergschrund was not very wide and we managed to cross it without too much difficulty, although we did belay each other in this spot.

Dinwoody Pass is on the skyline just right of center.

Looking north toward Dinwoody Pass from the base of Fremont Peak.

Titcomb Basin as viewed from Dinwoody Pass.

Once we gained a footing on Gooseneck Ridge, our route climbed up the ridge on good cramponing snow to Gannett’s summit ridge and then to the summit. We had a strange, deflating encounter on the summit which I wrote about in an article in Summit Magazine: Tales of Two Mountains.

Gannett Peak as viewed from Dinwoody Pass.

Just below Dinwoody Pass.

A crevasse on the Dinwoody Glacier.

Approaching the intersection of the Dinwoody and Gooseneck glaciers.

At a minimum, you need an ice axe and crampons for this route. Prudence dictates that you rope up for the glacier travel and, depending upon the condition of the bergschrund, you may need pickets or a couple of ice screws to set up a belay. Once we were on the summit, the crux was still ahead of us–the crux being the long walk back to camp. Our route covered 10 miles round trip. We started at 5:30AM and got back at dusk.

Our route from the base of Dinwoody Pass to the summit.

The highest point in Wyoming.

The long walk home.

Our sleep that evening was interrupted by one of the finest lightning shows imaginable as a storm came in after midnight and treated us to thunder and lightning for over an hour. At times there were so many concurrent flashes that the basin was lit up like daytime. There was a hardly a drop of rain. The next day we took it easy, slept in and took only short walks around the basin.

Taking in the view on our rest day.

All good things must come to an end and we started our long hike out. We hiked 12 miles and camped at Miller Lake which left us just 3 miles on our last day. Of all the trips I have taken into the Wind River Range, this one was the only trip blessed by great weather. August is the best time to travel in the range but I have been snowed on in August on 2 different occasions. The only bad weather we had was the delightful thunderstorm that was really more entertainment than anything. Our round trip and day hikes covered 53 miles.

Next: Scambles in the Lemhi Range