Life is a continuing series of juxtapositions, happiness/sadness, good/evil, dreams/reality, success/failure and on and on. The greatest juxtaposition seems to me to be the known versus the unknown. The interplay between this juxtaposition can either drive one to play it safe or seek out the unknown. Regression is the likely outcome from playing it safe. Progress comes from confronting the unknown. When I graduated from college, I was determined to seek the path of progress. The Summer of 1973 at Crater Lake National Park taught me many lessons that would aid my journey through life.

Natural Disaster/Fortuitous Creation

Crater Lake was formed as a result of the collapse of a giant volcano, Mount Mazama, around 7,500 years ago. In the intervening years, the huge caldera formed by the collapse has partially filled with water forming a massive lake, known for its deep blue color and water clarity. It is the deepest lake in the United States with a depth of 1,950-feet. There are 2 small islands in the lake: Wizard Island, a volcanic cone that formed after the collapse and the Phantom Ship, a jagged island 500 feet long and 200 feet high. Above the lake’s surface, the caldera walls rise precipitously, forming rugged cliffs and jagged peaks.

An artist rendition of Mount Manama before the mountain collapsed. Crater Lake Natural History Association Slide

Crater Lake National Park was established on May 22, 1902. Crater Lake Lodge opened in 1915 and the scenic Rim Drive was completed in 1918. Seventy-one years after the park was established, I graduated from the University of Michigan with a degree in Natural Resources. To be honest, the degree had not prepared me for any real-world job. Nevertheless, my life took a decisive turn when I was offered a seasonal Park Ranger job at Crater Lake National Park.

Beauty/Loved Too Much

The author and adventurer Jack London gushed about the lake’s beauty:

“I thought I had gazed upon everything beautiful in nature as I have spent my years traveling thousands of miles to visit the beauty spots of the earth, but I have reached the climax. Never again can I gaze upon the beauty spots of the earth and enjoy them as being the finest thing I have ever seen. Crater Lake is above them all.” —Jack London, 1911

Crater Lake’s beauty is almost surreal. It is a place almost too fantastical in appearance to comprehend. A giant lake, high in a fractured mountain with deep blue water that mesmerizes those lucky enough to see it. Visitors arrive in droves to experience “the finest thing” Jack London had “ever seen.”

For the Park Service, juxtaposed against its duty to protect the Park’s unique beauty was the mission of servicing and protecting tourists. As an outdoor wilderness lover and a seasonal employee, I became a cog in this vibrant juxtaposition. The variety of people who visit our National Parks is an extreme spectrum from sightseers to scientists, from city folks to off-the-gridders, from the honest to the dishonest and everything in between. This conglomerate of humans fuels the experience of a National Park’s employees in many unpredictable ways. While this remembrance is not about the Park per se, it is a story told under the Park’s influence.

Arrival/Revivals

While my previous brief forays in the West had convinced me that the West and its mountains were where I would thrive, I had not figured out a career path that would allow me to live in the West. Working as a seasonal Ranger for the Park Service and living full-time in a mountain environment was a start, an opportunity to learn skills that would be useful for the rest of my life and let me actually breath fully in a mountain environment.

I arrived at the Park on May 10th to find the landscape still buried in deep snow. The Park gets an unbelievable amount of snow each year. In the 1990s, average snowfall was 493 inches a year. More recently, snowfalls have decreased. Nevertheless, since 2010, snowfall has averaged 377 inches per year which is over 34 feet of snow. As a result, the only road open in May was OR-62 which traversed the Park south of the lake and the road from OR-62 to the crater’s rim at Rim Village.

There were no crowds of tourists. The lodge and campgrounds were closed. A small cadre of full-time employees manned the headquarters and maintained the few miles of park roads that were open. I was temporarily assigned to a cabin near the headquarters. The cabin entrance was reached through large steel tube that led from the road to the front door as the cabin was still mostly buried.

Most of the seasonal employees were schoolteachers and college students who would not arrive until early June. As a result, the only seasonal Rangers until then were myself and 2 veteran seasonal Rangers, Dave Panebaker and Bruce Kay. As an early arrival (even before ranger training started), I was put to work. Most of the tasks were mundane but occasionally I was sent out in a Park Service vehicle to patrol the roads. Because the Park was not yet inundated with visitors, for 3 weeks we had the Park nearly to ourselves. It was 3 weeks of pure delight.

Inexperience/Experience

Dave Pannebaker was an old hand at the seasonal Ranger game. The 3 weeks I spent working under Dave’s direction gave me a chance to learn from his experiences. He was an excellent mentor. It was only fitting that my first climbing adventure of the year was with Dave. I had focused my climbing desire on Union Peak, a volcanic plug located in the Park’s southwest corner. The peak is an eye-catcher as it climbs up sharply out of surrounding rolling, forested terrain. Dave had climbed it several times. I had no experience climbing in snow. Dave assured me that it was safe to climb despite the snow that blanketed the route.

The snow along the road at the trailhead was 6 feet deep. We brought 2 pairs of 1940 vintage Park Service snowshoes. At the trailhead, we found the snow was bomb-proof and left the snowshoes behind. Most of our route followed a section of the Pacific Crest Trail. Even though the tread was buried by the snow, it was easy to follow as it was marked by PCT emblems placed high up on the trees.

The peak’s North Face was covered in snow. The climb was my first opportunity to use an ice axe. Dave instructed me in its use. Despite the steep snow, the climb was easy. On the summit, I had an endorphin rush. Yea! That is mountaineering, this is what it is all about, I thought.

Staying at Home/Going it Alone

One downside about working as a seasonal Ranger is that your days off seldom coincide with the days off of your coworkers. After other seasonal employees started to arrive, I found my days off didn’t mesh with any employees who were interested in climbing. While in prior years I had hiked across the Grand Canyon and climbed Mount Whitney solo, I really wasn’t alone on those trips given the crowds on those trails. So 1973 really was my first time that I would hike and climb truly alone. While the Park was not exceptionally wild country, there are plenty of hazards. I found traveling alone was a mental challenge. The desire to climb peaks versus the fear of going into the unknown alone would continue to cause internal conflicts all summer. Most notably, later in the year, I turned back halfway up Mount Shasta.

The maintenance crews start plowing the Rim Drive around the first of May. The crew would open the road piecemeal as sections were cleared. Soon after the first section from the Rim Village to the Watchman parking lot was open, I took off to climb Watchman Peak solo. Watchman Peak is located on the west side of Crater Lake. An Observation Station was placed on the peak’s summit in the 1920s where it served as an interpretive center and a fire lookout. There is a trail just under a mile long that leads from a parking lot to the 8,013-foot summit, but it was covered by snow. The snow made the ascent more than a hike.

The park was still devoid of tourists and I had the incredible viewpoint to myself. Although I was not fasting or staying out overnight, my sojourn was, in a way, a mini vision-quest. From the summit, I could see many snow covered peaks. In the south, Mount McLoughlin and Mount Shasta beckoned. To the north, Mount Bailey and impossible-looking Mount Thielsen set my imagination running.

Civilian/Ranger

As more and more of the seasonal employees dribble in, I marveled at the wide variety of personalities that were drawn to seasonal Park Service work. Many had worked at the Park in previous seasons. A few had spent many Summers working seasonal jobs. These seasonals would be the face of the National Park Service for the visitors. Everything from maintenance to visitor center operations to interpretive walks to campfire programs to law enforcement was the responsibility of the seasonals. During the Summer, the full-time employees fade into the background to do paperwork and stand in reserve in case emergencies crop up. The seasonal employees were “living the life” while the full-time employees were “doing a job.” Why, I thought, would I want to be a full-timer?

After 3 weeks as an ad hoc Ranger, it was time to begin training. Training would transform us from civilians to full-fledged Park Service employees. We would learn our duties and that these duties must be preformed with an earnestness that far surpassed most jobs. Topics included law enforcement, first aid, mountain rescue operations and coping with adverse mountain conditions. It was an opportunity to learn skills such as rappelling and search and rescue procedures from experienced mentors.

For much of the training, those of us designated as seasonal Rangers were separated from those designated as seasonal Naturalists. The law enforcement and ethics training was intensive and full of war stories. It was conducted by 2 veteran Park Service employees. Both had at one time been Chief Rangers, a position many considered the pinnacle of the Ranger profession. We were taught that, no matter what our titles, we were responsible for assuring that visitors were treated politely and ethically, that the park’s resources were preserved and that our behavior had to be above reproach. Nobody from the Superintendent on down was above picking up a piece of trash or helping a visitor.

We were also taught about the importance of our uniforms. There is no doubt that men love uniforms. Whether sports uniforms or Park Service uniforms, men take to them. I was no different. The Park Service uniforms were the pinnacle of my uniform fetish never to be equaled again. Every workday, the uniform was put on with meticulous care to insure that all knew that I proudly represented the National Park Service.

Elation/Let Down

Training was over and the tourists were pouring in. It was time to undertake the position that I was hired to undertake. My brief days of patrolling roads and hanging out with the full-time employees were over. I was assigned with 2 others to operate the south entry station. I was now basically a cashier with a uniform. Despite the mundane job, I still had my weekends for adventure.

Safety/Summit Fever

After the successful ascents of Union Peak and The Watchman, I set my goal of climbing more difficult peaks and improving my skills. The first one on my list was Mount McLoughlin. It was a larger, more imposing version of Union Peak. Mount McLoughlin is a steep-sided, long dormant, composite volcano, located south of the park. It is not only a prominent landmark for the Rogue River Valley but is also highly visible from Crater Lake’s Rim Road.

The trail to the top was nearly 5 miles long and much of the upper way was still mostly covered by snow. It would be my first experience climbing and descending serious snow slopes alone. The trail was marked by blazed trees down low and some rock cairns above. Climbing alone, I suffered through recurrent thoughts about the wisdom of my endeavor. Every time I stopped to catch my breath, self doubt and fear would take over my mind. “Is this really smart?” “Who do you think you are?” Yet, the closer I got to the top, the more summit fever clouded my mind. “You can’t stop now.” “You are so close.” Finally, somehow, I entered into a meditative state, concentrating on each step and tuning out the thoughts. Entering the meditative state was a skill that would come in handy the rest of my life and not just for climbing.

Safety/Risk Taking

Once Mount McLoughlin was conquered, my confidence level was peaked. Mount Thielsen was next. Thielsen rises up menacingly, just north of the Park. It looked impossible. Nicknamed the lightning rod of the Cascades because of its needle-shaped summit, it is the type of peak that emits a siren song that calls out and hypnotizes climbers. Stating that it rises abruptly to form an impressive spire with towering North and East Faces is not the whole story. It is a volcanic remnant composed of unstable, broken rock. The objective hazards are the real story of this peak. It is a completely different mountain from Mount McLoughlin.

Two weeks earlier sitting on top of The Watchman, I had vowed to climb it—someday. Now that the day arrived, I wasn’t so sure. In 1972, I climbed Mount Whitney, the highest point in the Lower 48 states but Thielsen was in a different league—not an alpine peak but a dark, scary looking sentinel. At that moment, it was the mountain of my fears. I later found there would always be another mountain, both figuratively and in reality, to fear.

Dave Panebaker had climbed Thielsen but he and I no longer had days off that coincided. Dave introduced me to Scott Ranger, a seasonal Naturalist, who also wanted to climb the peak. He and I shared the same days off. Scott was not a mountain climber. I was still only a climber by desire, not by training or experience. Nevertheless, one beautiful June day Scott and I set out to climb the “lightning rod.”

Our route, described to us in detail by Dave, would climb the peak’s West Ridge. We followed a trail to the base of the ridge and started up. It was my first real indoctrination to the “hell” of loose scree and talus—one step up, slide back a half step. The struggle with loose talus seemed interminable. Try as I might, I could not put my mind into the meditative state I had reached on Mount McLoughlin. Neither of us wanted to look weak or inexperienced so we quietly endured our suffering. Finally, we reached the base of the summit block. The summit block, which looked steep, difficult and exposed from the distance, did not look any easier close up.

“We should be happy just to have reached this point,” Scott pointed out as we stared at the route ahead. “We’ve come this far . . .,” I answered, my voice tailing off. We were both silent for 5 minutes as we contemplated the task ahead. While I thought that maybe Scott was right, giving up after suffering through West Ridge talus seemed to be unforgivable.

Finally, Scott declared “I am not going any farther.” The little climber that could in my head took over. “I’m going to try it,” I said. “Are you sure? We should come back with someone who knows how to climb with a rope.” Scott made it clear he didn’t want me to proceed. “Dave said it wasn’t as bad as it looked,” I said as I started up, not feeling all that confident. “Dave is more experienced than us,” was Scott’s last effort to stop me. A parting shot that I took little solace in. Dave was right. The holds were plentiful and solid. There were no spots where falling seemed a likely proposition. I learned this day that “summit fever” was a powerful motivating force. It was also a two-edged sword. It provides motivation to push on but it can also cloud judgment.

Of Men/And Bears

My work hours were from 3:00PM-11:00PM. The last 4 hours at the entrance station saw little traffic. It not only kept me from joining others drinking in the bar at Rim Village but it also allowed me to pass the quiet hours reading such tomes as War and Peace and The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. While many nights no one came by the station after 8:00PM, one night my supervisor unexpectedly showed up. He told me to close the entrance station. “What’s up?” I asked. “Bears in the campground,” he answered.

We drove into the campground and found the 2 campground Rangers. They reported, somewhat breathlessly, that bears had harassed campers and raided a number of coolers. The campground was full as usual in July. Few of the campers had heeded warnings and taken any precautions to secure their food. It was pitch dark. The campers had been ordered to sit in their vehicles with the windows shut. Some looked perturbed and some looked scared.

My supervisor asked the campground Rangers where the bears were last spotted. “They are everywhere,” was the response. Neither of the agitated campground Rangers had actually spotted a bear. They based their answer on the path of raided coolers that they had followed. The supervisor said, “Don’t worry, the Bear Man is coming.” I had not yet heard of the Bear Man. I was intrigued.

A few minutes later, the Bear Man arrived driving a pickup and pulling a trailer consisting of a long steel tube with a gate on the back end. I expected to find the Bear Man would be a grizzled, old recluse. Instead he was a young, curly-haired man wearing jeans and a plaid shirt. He got out and debriefed the campground Rangers. Receiving what I thought was no useful information from that exercise, he said “Okay, got it.” He returned to the truck and got out a rifle and a small case. The case held darts that he would shoot from the gun to drug the bears.

He told us to be quiet. Stillness ensued. We soon heard metal clanking. In response, he deployed the 3 trucks and us around the area where the sound was centered. The lights of the vehicles were positioned to form lighted lines down the roads surrounding the area where the noise originated. Were were positioned so that if a bear crossed the light beams, we would see it. We were instructed to yell and attempt to drive the bear back into the area enclosed by the light beams. The Bear Man then crept into the darkness.

Less than 3 minutes later, I heard a pop. Soon after, a bear came slowly into the light beam in front of me and collapsed. The Bear Man followed. The bear was breathing heavily at first and then quietly as it drifted off into unconsciousness. After a quick inspection, the Bear Man looked up at us and said “She has a cub nearby. Look up in the trees.” Soon one of the campground Rangers shouted out, “Over here!” Fifteen feet up in a pine tree, there were 2 cubs staring down at us.

We were instructed to get a tarp from the truck. Then the 5 of us stretched the tarp out between us under the cubs, holding it off the ground. The Bear Man reloaded his rifle and shot a dart into one cub and then the other cub. The cubs were soon unconscious but they didn’t fall. So the Bear Man nonchalantly climbed up and pushed them out of the tree. One at a time, they hit the tarp like a ton of bricks. They were small but dense. Who was this man? He thought like a bear and had no fear.

It turned out the Bear Man was a research scientist, Michael McCollum, who was spending the Summer studying the Park’s bears. The park, like many units in the National Park system in the 1970s, had significant problems with bear/human conflicts. McCollum was studying bears with a goal of determining how best to handle the problem. The Park Service had closed the Crater Lake garbage dump, a major bear attractant, the year before and now the bears were even more of a problem as they looked for human food in other locations.

After we managed to get all 3 bears into the bear trap trailer, I asked him what he would do with them. He told me he would let them go the next day on the north side of the park. The next day was my day off so I asked if I could join him. He agreed. I spent my next 2 weekends helping him inspect captured bears. He was a wizard, skilled in catching problem bears or placing and baiting the traps for wild bears. In the case of wild bears, every time we drove up to a trap we found a snarling bear inside the tube. He would quickly tranquilize the bear. We would then pull the bear from the trap, weigh it, inspect and tag it. Radio collars were put on some of the bears. Then we would eat a sandwich while waiting for the bear to awaken. When the bear awoke and wandered away, we would leave.

Good/Bad

Criminals are also attracted to the National Parks. In 1973, crime was primarily limited to theft. Tourists are easy pickings for thieves as they are prone to either not lock their vehicles or to leave their valuables in plain sight in a locked vehicle. Thus bears were not the only predators roaming campgrounds at night. Dave Panebaker was primarily engaged in law enforcement activities that Summer and he was occasionally involved in investigating thefts. Catching stealthy thieves in the National Parks is not an easy task.

The seasonals assigned to the South Entrance Station were also assigned to live in the nearby 2-bedroom Annie Springs Cabin. I moved in on June 1st. Since I was the first to arrive at the cabin, I grabbed the bedroom with a single bed. When my roommates arrived, they were both pissed off and both tried to talk me into trading. I didn’t trade. As a result, there was little camaraderie at the cabin. Since we all were assigned to the same entrance station, we lived and worked together—fortunately not often on the same shift. My idea of living at the park and theirs differed. I was there to experience the park. They were there to party.

Our supervisor was an old seasonal who had worked at the park for over 20 Summers. He reminded me of Archie Bunker. I don’t think he had a really high opinion of the three 20-somethings he supervised. Nevertheless, he treated us kindly. He explained to us on the first day the entrance station was open how we were to account for money collected. This involved using an ancient cash register which generated a tape with an imprint of each sale. Additionally, when we rang up a sale, we placed a small blue slip of paper in the spot where the imprint was struck. The now-dated blue paper receipt was then given to the visitors as proof that they had paid the $3 entrance fee.

Our supervisor pointed out that, at times, the entrance station would be extremely busy. As a result, he said we would occasionally make errors as we made change. He said we would discover these errors when we did the accounting at the end of our shift. Some days we would be short and other days we would have extra money. He then gave us an envelope with $50 in ones. He said this was the slush fund. If we were short ,we could take money out of the envelope to balance the account and if we were over we were to put the extra money into the envelope.

I thought the entrance station was running smoothly. Then one day in early August, I was called into the Chief Ranger’s office. I was questioned about the slush fund and whether I had ever noticed my coworkers collecting money but not giving the visitors a receipt or not ringing up a sale? The questions all seemed mysterious at that point, especially considering I seldom worked with the same shift. When the interview was over, it was time for my shift to start. I drove down to the entrance station to find my supervisor manning the station. He told me that my roommates had been caught stealing money.

He said they were not registering the sales and giving visitors un-stamped receipts. “Undoubtedly,” he said, “the money was going into someone’s pocket.” “Even worse,” he said, “the slush fund was down to $8.” Then he dropped the biggest bombshell, telling me that, when confronted, my roommates tried to blame me. Lucky for me, a tourist had noticed that his blue receipt was devoid of printing showing he had paid. The tourist immediately stopped at the headquarters and reported this fact. An investigation ensued and it was determined that this never happened during my shift. When my shift was done, I returned to the Annie Springs Cabin to find the roommates were both gone. I never saw them again.

Friends/And Friends

After 2 weekends hanging with the Bear Man, my bear curiosity was satiated. I refocused on climbing. My friend Jay Weiss arrived at the park. Jay and I had met on a softball field at the University of Michigan in 1970. We have been friends ever since and have shared many mountain adventures over the years. Prior to his visit, we had twice backpacked together at Smokey Mountain National Park. He arrived on one of my days off. Almost immediately, we set off on a hike from Rim Village along the lake’s South Rim. The first stop was Garfield Peak. Garfield Peak is one of 3 peaks in the park reached by a trail. The trail is 3.5 miles long and gains 1,115 feet before reaching the 8,054-foot summit.

From Garfield Peak, we set out cross-country to Dyar Rock and then continued on to Applegate Peak (8,126 feet). This was roughly another mile of hiking through meadows interspersed with pines. Another spectacular day that would be long remembered. Mount Scott, the highest point in the park at 8,929 feet and the 10th highest peak in the Oregon Cascades, was our next destination. A 5-mile long trail leads to the summit, which was graced by a seldom-used fire lookout. Park employees could spend the night in the lookout. I took advantage of that benefit and reserved the lookout for a night. Jay and I were treated to a sunset, a starry night and a sunrise from that lofty perch.

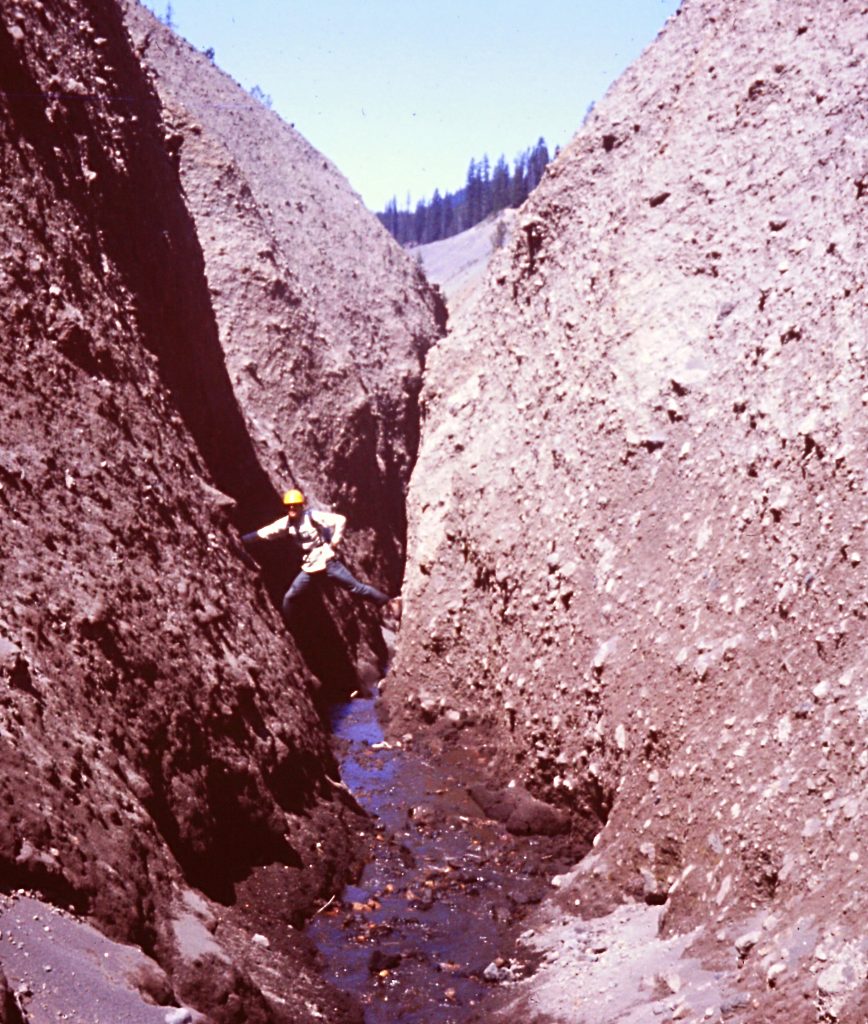

Jay headed down to the coast to scuba dive and then returned for my next 2 days off. Rather than climbing a peak, we decided to explore the bowels of the park—Lloas Hallway. Lloas Hallway is a 125-foot-deep gorge sliced through soft pumice by stream erosion. Think of a narrow Utah slot canyon with rock much softer than sandstone. It is located in the southwest corner of the Park and empties into Whitehorse Creek.

I was told that a trail once descended the canyon but we saw no evidence of a trail. The Park did not encourage visitors to explore the canyon because of the potential dangers and because the pumice is soft and easily damaged. There were no restrictions on employees. Jay and I put on hard hats and made our way down the canyon. The gorge was so narrow in spots that we could easily chimney down steeper sections.

The next day we set off for Mount Bailey (8,375 feet). It is a shield volcano located northwest of Crater Lake and due west of Diamond Lake and Mount Thielsen. The trail to the summit is nearly 6 miles long and gains over 3,000 feet in elevation. It runs through a flat covered by lodgepole pine and then climbs up through open stands of mountain hemlock and fir. The trail breaks out of the trees a mile from the summit. Dave Panebaker’s days off had changed. He joined us for the climb.

No Place Like Home/Nothing Better Than Family

I think a “wanderlust” gene is part of my DNA. However, I grew up in a family that seldom traveled. As a kid, a trip of 100 miles seemed like a journey to the end of the world. My dad had served in the Aleutian Islands during World War II and clearly felt he had traveled enough for one lifetime. So traveling to Detroit to watch a baseball game or to Logan, Ohio to visit my mother’s family was the extent of my travels as a kid.

It wasn’t until I started college that I was able to expand my horizons and act on my desire to see faraway lands. So imagine my surprise when I received a letter (remember letters?) from my mom telling me that she and my siblings were driving to Oregon to visit me in mid-August. Even more surprising was the news that my stay-close-to-home Dad was also coming, albeit by train. If the West and mountains were new, strange and a little mysterious to my family when they left on their trip, by the time they arrived in Oregon they were fully acclimatized and ready for adventure. That evening, we drove down to Klamath Falls and picked up my dad at the train station.

The next day, minus my dad who decided to spend the day at Rim Village, we embarked on a drive around the Crater Lake Rim Road. After taking in several view points, we stopped at the Cleetwood Cove trailhead. The Cleetwood Cove Trail leads down to the boat dock on the north side of the lake in 1.1 miles with a 700-foot loss in elevation. During the Summer, a concessionaire operates boat tours on the lake which combined a tour of the lake with a stop over at Wizard Island. The large open-air boats were the perfect vehicle for touring the lake. We took advantage of the opportunity to get off the boat at Wizard Island and take a later boat back.

Wizard Island is a 763-foot cinder cone and is roughly 6,000 years old. Much to my surprise, all of my family were enthusiastic about hiking the mile-long trail to the top of the island. Even more surprising was how well they all preformed on the hike, something none of them had ever done before.

The visit was a watershed moment for all of us. For me, it demonstrated that I was free to stay in the West with the acquiescence of my family. For my family, it was the awakening to a broader world. All of them eventually moved West. The family left for Michigan, leaving my 16-year old brother Bill to return later with me when I returned for graduate school. He and I climbed Hillman Peak, the last hike of the Summer. It was a short climb from Rim Road to the 8,151-foot summit but a long journey for bonding 2 brothers.

Beginnings/Endings/Beginnings

Crater Lake was the start of my life in the West. During the 17 weeks my seasonal job lasted, I was able to have my first experiences using snowshoes, an ice axe and skis. I learned route-finding skills and how to overcome fear of the unknown. The next year, I took a seasonal Ranger job at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks and it wasn’t until 1982 that I returned to Crater Lake. Although the Crater Lake experience ended, my journey had just begun.

I had a lot of adventures that Summer that I did not recount in this article. Dave Panebaker down in the Scoria Cone vent.

NEXT: Days in Heaven: Sequoia and Kings Canyon 1974, California

To read about another Crater Lake adventure see: Skiing the Rim Road Around Crater Lake, 1990