ARTICLE INDEX

“Dreaming, after all, is a form of planning.” —Gloria Steinem

After working as a seasonal Ranger at Crater Lake National Park during the summer of 1973, I envisioned a career as a Park Ranger. I started graduate school that Fall but quickly decided a Masters Degree in Outdoor Recreation Management would not advance my new career goal. When I finished the Fall term I chose to save my money and did not enroll the next term. I knew my future was not in Michigan. Instead it was in some as of yet undetermined western state.

Although I had an offer to return to Crater Lake the following May to once again work at the Annie Creek Entrance Station I hoped for a more exciting offer from a more mountainous park. On April 1st my hopes were answered when Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks’ Sierra District offered me a six month appointment manning the Lookout Point Ranger Station. I was delighted.

My 1972 ascent of Mount Whitney left me longing to return to John Muir’s “Range of Light.” I knew nothing about the west side of the Sierra Nevada mountains or even where Lookout Point was located. My lack of knowledge was immaterial. My anticipation of the experiences that this job would entail surged through me like a bolt of lightening. Never mind that at this point in my life, what I anticipated I would find at a destination was likely a romanticized version of what I would actually find on the ground. It was the Sierra Nevada and that was all I needed to know. I immediately accepted the job.

“And I can’t wait to get on the road again.” —Willie Nelson

I loaded up my AMC Gremlin which was my trusted transport across the West for much of the 1970s. It had no air conditioning or stereo but it was economical to drive. I had honed my packing skills over the years. Everything I needed, from kitchen utensils and bedding to hiking equipment and uniforms, fit neatly into that small car.

I planned my route to California to feed my wanderlust. I devoted six days to sightseeing. After crossing the flat, mountainless void of the midwest, my route would shimmy through the mountains and deserts of Colorado, Utah and Nevada. An area I considered to be the heart of the American West. On April 26th I was on my way.

The first day I drove from my parents home all the way to Iowa City, Iowa, 420 miles—without stopping. After gassing up and eating, I continued driving to Kearney, Nebraska another 430 miles. I checked in to a motel and found a restaurant in Kearney, a small college town, along the Platte River. The town felt comfortable. The people were friendly. The food was good. The land was still flat but the changing terrain promised the West was drawing near.

The next morning I was up early and on the road without bothering to eat. Driving on Interstate 80 along the Platte, I imagined the Rocky Mountains would soon come into view. I followed the freeway this far the previous year on my way to Oregon. One hundred and seventy miles later I turned onto Interstate 76. I would soon reach Colorado. The real or at least imaginary American West?

“Often a dream, sometimes a metaphor, the American West is a place that millions of people can visualize. Certain landscapes of mountain and desert are instantly recognizable. So are certain residents, if they ride horses and wear broad hats or feathered headbands. In these nearly universal images, the West seems grandly conceived and easily explained. It is the West that serves as popular myth and national symbol.” —The Oxford History of the American West

What was the American West anyway? Growing up on television westerns, my vision of the West was full of misconceptions and delusions about the vast area that stretched before me. When I was a kid, Matt Dillion was the quintessential forthright western man. He was centered in Dodge City, Kansas hardly a true western local. Dillion’s Kansas was a dusty, black and white mirage of small towns, cows, personal tragedies, sudden death and rugged individualism. Richard Boone’s Paladin character in the television show Have Gun Will Travel also influenced my understanding of western mores. Paladin traipsed all over that West from California to Colorado and Montana to Arizona. His West was a land of deserts and mountains. His West was also, for the most part, a land of small parochial towns filled with desperate characters often in need, often ruled by brutal characters who sought dominion of the empty deserts and mysterious mountains. Paladin’s West would prove to be closer to the real but quickly disappearing American West that I had anticipated. Still, it was also a mirage. All of these imaginary scenes floated in and out of my head as I drove. The American West was too big and diverse for me to comprehend then and still to some extent is now.

What was the American West anyway? Growing up on television westerns, my vision of the West was full of misconceptions and delusions about the vast area that stretched before me. When I was a kid, Matt Dillion was the quintessential forthright western man. He was centered in Dodge City, Kansas hardly a true western local. Dillion’s Kansas was a dusty, black and white mirage of small towns, cows, personal tragedies, sudden death and rugged individualism. Richard Boone’s Paladin character in the television show Have Gun Will Travel also influenced my understanding of western mores. Paladin traipsed all over that West from California to Colorado and Montana to Arizona. His West was a land of deserts and mountains. His West was also, for the most part, a land of small parochial towns filled with desperate characters often in need, often ruled by brutal characters who sought dominion of the empty deserts and mysterious mountains. Paladin’s West would prove to be closer to the real but quickly disappearing American West that I had anticipated. Still, it was also a mirage. All of these imaginary scenes floated in and out of my head as I drove. The American West was too big and diverse for me to comprehend then and still to some extent is now.

As I drove the reality of the West of 1974 flowed visually into my conscience with each mile I traveled. It was at first sagebrush prairie and freeway. Then it was a big city, Denver, backed by glorious mountains. Driving past and ignoring Denver, I entered the mountains. I made my first stop at Loveland Pass, 11,911 feet. Huge snowbanks still bounded the parking area. The air was chilled. The American West was a land of towering mountains.

I continued on, driving through the mountains and then descending to Glenwood Springs. The last few miles that day traversed Glenwood Canyon. The Colorado River carved the narrow, scenic canyon over the course of three million years into a transportation bottleneck. It is said the canyon was so difficult that the Utes avoided it. Railroad tracks through the canyon were completed in 1887 and in 1899 a dirt road was built paralleling the tracks. This road had eventually evolved into the two lane highway that I drove. The road through Glenwood Canyon was nothing like it is today. The fifteen mile stretch of Interstate 70 through the canyon would not be completed until 1992. So, instead of driving the present engineering marvel, I experienced the narrow canyon in a more primitive state. The American West was a land in a constant state of transition.

I spent the night in a vibrant, growing Glenwood Springs. The town is at the confluence of the Roaring Fork River and the Colorado River. I had encountered the river in 1972 when I had hiked across the Grand Canyon. The Colorado River was legendary. How many books had I read that featured the Colorado River? How many Westerns movies depicted this river? The steep terrain on either side of the ever expanding town added to the river and the town’s western but changing ambiance. The American West was growing.

I had never heard of the Colorado National Monument until a waitress told me that if I only did one thing in Glenwood Springs, visiting the monument was “the one thing.” The Park Service describes the Monument as “one of the grand landscapes of the American West.” The description was backed up by the scenery. The main activity for visitors is to drive the Rim Rock Drive past sandstone monoliths and panoramic canyons. I was the quintessential tourist at this point. I drove the road, stopped to take photos, and then drove on, heading for Moab, Utah. The American West is amazing scenery.

From the monument the road dropped out of Colorado and into the eastern Utah desert. Utah State Police patrolled the in pairs of police cars mimicking a sheriff’s posse. Small gas stationed still thrived along the two lane route, their final demise awaiting the completion of the freeway. The country was not yet homogenized. There was still the human folly of doomed small hotels, eclectic diners and wooden billboards coloring or, if you prefer, cluttering the landscape. The American West was a big and mostly empty land constantly booming and busting.

I pulled into Moab, Utah late in the day. Unlike the Moab of 2020 the 1974 Moab was still a small Western town off the beaten track. It’s location next to Arches and Canyonlands National Parks portended that it would soon evolve into a tourist gateway. It was evident that tourism was beginning to subsidize the local economy but the tourism industry did not yet dominated the town. Everything was local. No chain motels. No chain restaurants. The locals were actually people who had been born below the sandstone cliffs. They were genuinely happy to welcome visitors. I secured an $8 motel room and had a chili burger and fries for dinner. The American West was the promise of things, good and bad, to come.

The next morning I drove the short distance to Arches National Park. The park was designated as a National Monument in 1929, and redesignated a National Park in November 1971. Arches contains more than 2,000 natural sandstone arches of which Delicate Arch is the most famous. The park’s high desert terrain receives less than ten inches of rain a year. Elevations range from 4,085 feet at the visitor center to 5,653 feet on Elephant Butte. I made the incredible hike to Delicate Arch. There is a reason Delicate Arch is found on every Utah license plate. It is one of the world’s most visually outstanding geologic features. Delicate Arch is only 52 feet high but, due to its freestanding location on the edge of a cliff it is breathtaking. The American West is filled with unique features.

Back at the car, I drove on to Bryce Canyon National Park. Once again, I found an $8 hotel room just outside of the park. Bryce Canyon National Park is not a canyon per se but a collection of giant stone amphitheaters and hoodoos carved into the eastern side of the Paunsaugunt Plateau at elevations ranging between 8,000 to 9,000 feet. The hoodoos were formed by frost weathering and erosion of red, orange and white sedimentary rocks. The area was settled by Mormon pioneers who drove the Native Americans out in the 1850s. The park was named after homesteader Ebenezer Bryce. Bryce Canyon was designated as a National Monument by President Warren G. Harding in 1923 and was redesignated as a National Park by Congress in 1928. Like my visit to the Colorado National Monument, I reverted to an American tourist. I drove along the rim, took a few photos and quickly headed on my way. The American West is a conquered land.

Zion National Park was my next stop. The park is centered around Zion Canyon a 15 miles long, 2,600 foot deep gorge cut by the North Fork of the Virgin River through Navajo Sandstone. Park elevations range from 3,666 feet to 8,726 feet. It is a meeting ground for the Colorado Plateau, Great Basin, and Mojave Desert ecosystems. In 1909, President William Howard Taft designated the canyon area Mukuntuweap (a Native American name) National Monument in order to protect the canyon. Ten years later Congress redesignated the monument as Zion National Park, changing the name to Zion to honor the Mormon settlers and to minimize the Native American heritage. I hiked a trail to the top of the rim and discovered my new hiking boots were blister generators. The American West was a land that required its inhabitants to disregard the past as well as possess toughness of mind and body.

After spending way too long on the hike, I was behind schedule. So, I drove to Lone Pine, California through Death Valley National Monument in a rush. I was disappointed. After watching hundreds of episodes of Death Valley Days, I had no time to explore that difficult terrain. I could only bookmark Death Valley in my mind. I knew I would have to return. The American West was a land of infinite possibilities.

Death Valley looking west from Badwater to Telescope Peak. It took me five years but I did return to climb Telescope Peak.

My final day on the road I drove from Lone Pine to Three Rivers, California and the headquarters of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Driving down California Highway 119 along the Kern River I encountered signs notifying Californians of how many people had drowned in the Kern and advising people to stay out in the water. The signs are still there today. The only difference is that the number of drownings have significantly increased as many do not heed the warnings. The American West was a land of many dangers.

Three Rivers was a small, hot town east of California’s Central Valley and its orange groves. It felt like a place Paladin would have visited. The low elevations around the town consisted of what I would learn was the California Foothills ecosystem highlighted by poison oak, blue oak, foothills chaparral and yucca plants in a steep sided river valley. The American West was a land of unique enchantment.

That night, I tallied up the cost of my journey. The cost of living was considerably less in 1974. Motels were cheap. The Motel 6 franchise name was based on the chain’s rooms originally costing $6 per night. While I never managed to stay in one for $6, I did stay in one that charged $7.95. The most I paid for a room was $10. The most I paid for a gallon of gas was 60¢. Five dollars for a meal would have been an extravagant expense. The trip cost me a grand total of $161.45 which included six nights in motels, all my meals and gas.

“Arriving at one goal is the starting point to another.” —John Dewey

I spent the evening in a Three Rivers motel and ate dinner in a Mexican Restaurant (my first). The next morning I reported to the park headquarters at Ash Mountain. It was immediately obvious that the Sequoia and Kings Canyon operation was a much bigger operation than Crater Lake National Park. The headquarters area included a visitor center, a large administrative building, a dormitory and a large complex housing the fire and maintenance divisions. Many people were coming and going in a beehive-like flurry of orchestrated activity.

After signing numerous employment documents I was introduced to and welcomed to the park by the Chief Ranger and the assistant Chief Ranger, Richard Powell. I later learned that Powell, while working at Death Valley, had been part of the law enforcement team that had arrested the infamous Charlie Manson and his clan. He walked me over to the Sierra District offices where I met my boss, Paul Fodor, the Sub-District Ranger and Alden Nash, the District Ranger.

After signing numerous employment documents I was introduced to and welcomed to the park by the Chief Ranger and the assistant Chief Ranger, Richard Powell. I later learned that Powell, while working at Death Valley, had been part of the law enforcement team that had arrested the infamous Charlie Manson and his clan. He walked me over to the Sierra District offices where I met my boss, Paul Fodor, the Sub-District Ranger and Alden Nash, the District Ranger.

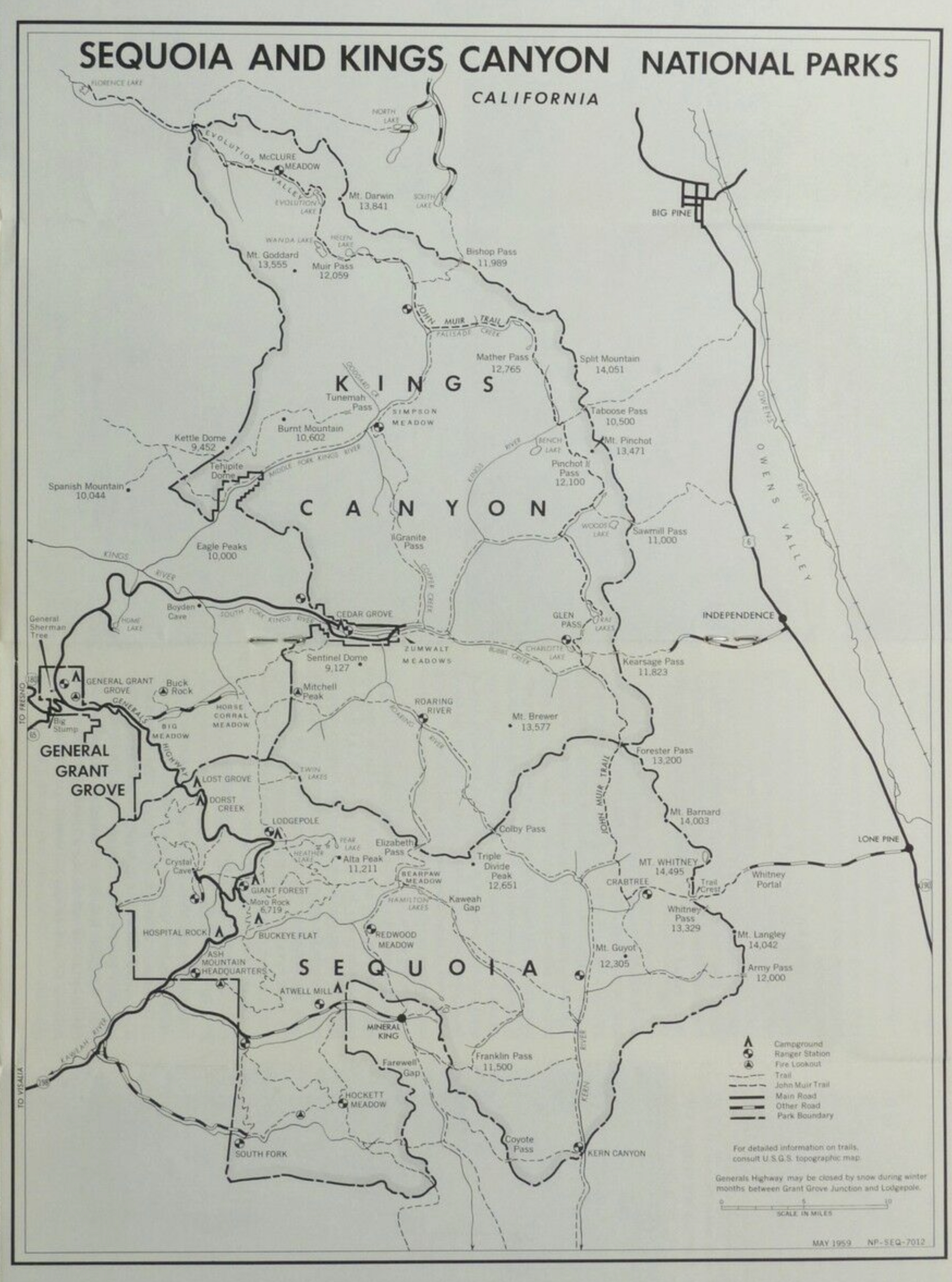

The Sierra District managed almost all of the park’s backcountry as well as a small chunk of front country west of Mineral King. The backcountry was managed through fourteen seasonal Backcountry Rangers. The section of front country was where I would work along with two other seasonal Rangers. This section of front country covered elevations that ranged from 4,000 feet to 9,000 feet. The terrain varied from steep, difficult canyon country to high ridges with spectacular groves of giant sequoias.

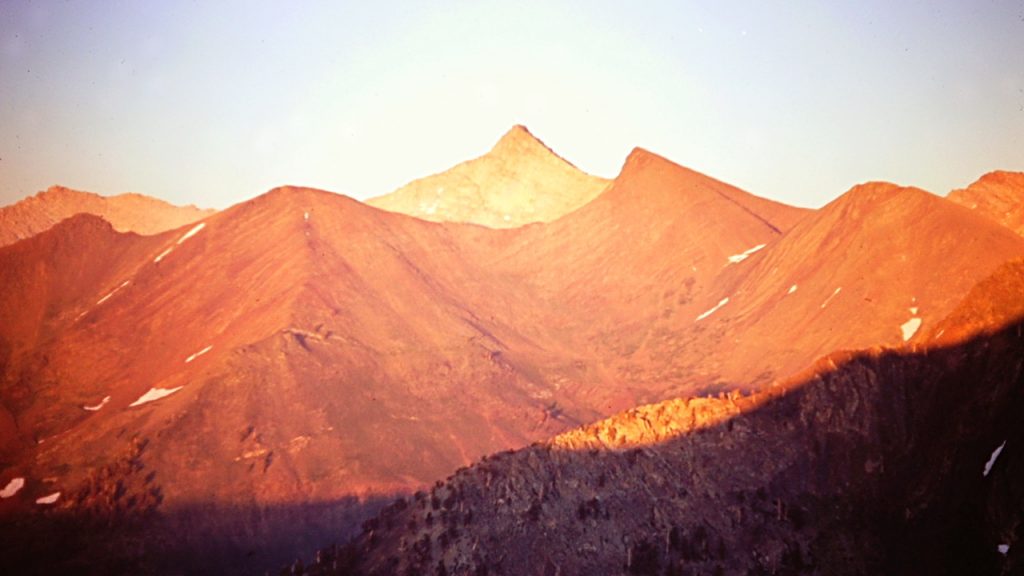

“. . . the mighty Sierra, miles in height, and so gloriously colored and so radiant, it seemed not clothed with light, but wholly composed of it, like the wall of some celestial city. . . . making a wall of light ineffably fine. Then it seemed to me that the Sierra should be called, not the Nevada or Snowy Range, but the Range of Light.” —John Muir

The Sierra Nevada Mountains stretch 400 miles from north to south and are 70 miles wide. The range encompasses the highest point in the contiguous United States, Mount Whitney, the largest alpine lake in the United States, Lake Tahoe, three national parks, twenty wilderness areas, and two national monuments. Yosemite National Park is one of the worlds most impressive glacially sculptured terrains and the most famous of the three parks. Yet, in my mind, Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks protected the heart of the range.

The parks, located in the southern Sierra Nevada Mountains, were established in 1890 and encompass 2,300 square miles of mountainous terrain. Sequoia is the southernmost of the two parks. Kings Canyon National Park, originally named General Grant National Park, the largest. It was expanded and renamed to Kings Canyon National Park in 1940. The two parks have been jointly administered since 1943.

Both parks start in the west as low elevation foothills and then rise in a series of giant steps to lofty divides including the Great Western Divide and the Sierra Nevada crest. Elevations range from under 1,700 feet to 14,505 feet on Mount Whitney. These parks house large rivers, giant sequoia groves, deep canyons, multiple 14,000-foot peaks and many miles of alpine terrain.

“Our life is frittered away by detail. Simplify, simplify.” —Henry David Thoreau

After a brief orientation I was sent to my duty station, the Lookout Point Ranger Station. The Ranger Station was located at 4,000 feet next to the Mineral King Road. It was hot country, not the alpine terrain I had envisioned. Two maintenance men accompanied me. They opened the station, turned on the water and enlighten me on the stations eccentricities.

The station was a four room adobe building. The walls were two feet thick. Even though the outside temperatures often exceeded a hundred degrees, the thick walls and large soffits on the building kept the temperature inside comfortable. There was no electricity or generator. It had a propane refrigerator, water heater and heater. The furniture was well used but comfortable.

The phone was activated by a hand crank. The phone was part of a party line. If you grew up in the 1950s you probably had experience with party lines. These systems were first used in 1878 and were widely in use when I was a kid. There were six phones on the line to Lookkout Point. The phones used a code ringing system. Each phone had its own distinct ring using a combination of long and short rings. If you were talking on a party line every other phone on the line could be used to eavesdrop on the conversation by simply picking up the phone. While eavesdroppers on the party line in my home when I was young would drive my Mother to distraction, it was not a problem at Lookout Point. The phones were seldom used by anyone.

There was only one annoying aspect of my time at this station. Every night as I started to drift off to sleep creatures in the attic started to party. I never figured out if it was mice or lizards but the racket was something else. I imagined animals chasing other animals in circles around the attic. After an hour or two silence would ensue.

Even though Lookout Point was a Ranger Station, few visitors stopped at the station to get information. Since I was seldom at the station this was probably a good thing.

“Everything that has a beginning has an ending. Make your peace with that and all will be well.” —Jack Kornfield

Since, there were few early season visitors venturing into my area, I was temporarily assigned to a crew of seasonal firefighters who were digging fire lines on Redwood Mountain in preparation for a prescribed burn. I was not happy with this development which I saw at first as a demotion. “I was a Ranger, not a manual laborer,” I told myself. That folly of my youthful thinking would soon melt away. My original disappointment was replaced by a respect for my coworkers and an understanding of the importance of the project. This assignment started on May 6th and lasted all month. In many ways this task was endless.

The Redwood Mountain Grove, located on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada in Kings Canyon National Park, is the largest giant sequoia grove in the world. These massive trees grow only in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, between elevations of 4,000 and 9,000 feet. Sequoia groves are not limited to giant sequoias as many different tree species are found within a grove.

The Park Service developed a program of prescribed burns, starting in 1969, to both reduce the accumulation of fuels and to stimulate giant sequoia reproduction. The large fire scars visible on many of the giant sequoias demonstrated that the big trees were able to resist ground fires. While the trees are resistant to ground fires, the historic “Smokey the Bear” put out ever fire management policy lead to the build up of excessive fuel on the forest floor. The fuel build up increased the risk that a fire would spread into the canopy. The prescribed burns were calculated to insure that the interplay between fire and the trees would revert to a natural process. If the prescribed burns successfully eliminated the excess fuel, future natural occurring fires would burn along the ground and not spread into the canopy.

“When hearts are high the time will fly so whistle while you work.” —Frank Churchill and Larry Morey

I worked primarily with the members of the Ash Mountain Fire and Helitack Crews. They had already been digging fire lines for the six previous weeks. I was the only person who had not grown up in the Central Valley. So, I was the proverbial tenderfoot. The crew was a mix of personalities—all were under 25 years old. One was the designated cook. He stayed at the large lodge we used as a base and did all the equipment maintenance, cooking and housekeeping.

Each day started with a long walk to where the previous days work had ended. To be a member of a helitack or fire crew is to be both mentally tough and incredibly fit. At first I was always falling behind. It took me two weeks of struggling to get even close their physical fitness. They kindly waited for me to catch up both out of empathy and so they could good naturally tease me. I learned a lot about applying myself to hard physical work and enjoying and surviving an endless task over the course of four weeks. Redwood Mountain was an amazing place to work. We saw no visitors. The giant trees silently stood over us, as they had over the forest floor for at least a thousand years.

At times we had to dig down through three or more feet of debris that had fallen to the ground to reach mineral soil. Occasionally, we would come across a sequoia branch that had fallen to the ground and was bigger than most Idaho fir trees. In the evening we would eat, read and talk. The next morning we were back on the fire lines digging away.

I returned to Lookout Point on the weekends. The second weekend I returned to the station from Redwood Mountain after dark to find someone had broken into the station. The glass on the backdoor was broken. There was blood on the sill and the door handle. Inside I found someone had slept in my bed and got a small amount of blood on the sheets. No one was in the station and as far as I could tell, nothing was missing. I reported the incident to Dispatch. Dispatch told me the culprit had turned himself in.

In late May snow line was around 9,000 feet. After trudging around in the redwoods for many days I was anxious to get into the high country. On May 25th, I made my first significant hike into the high mountains. The trail to Sawtooth Pass, named the Monarch Lakes Trail, leaves Mineral King and climbs to Ground Hog Meadow in a mile with 920 feet of elevation gain. Just above the meadow I reached snow. From that point on I walked on Sierra Cement—hard packed snow. The Sierra Cement moniker is well earned. The snow invariably supported my weight.

Although the trail switchbacks back and forth through stands of fir, the tread was buried under snow. I roughly followed its route by following the tracks of prior hikers and by marking my progress on the USGS quadrangle map I carried. I found the signed trail junction for the trail to Cobalt and Crystal lakes. Parts of the next two switchbacks were partially melted out. From the junction, I followed the trail as it returned to the Monarch drainage. The climb was relentless from this point to Lower Monarch Lake. From the lake, the trail was covered by snow all the way to Sawtooth Pass. I reached the pass after another 1.3 miles and another 1,200 feet of elevation gain. The hike took me from the Spring-like conditions on the Mineral King valley floor to Winter-like conditions on the 11,715 foot pass. I briefly had the pass to myself. Sitting there, I once again experienced an endorphin and vitamin D induced altitude elation. The same state of “exhilaration” that has drawn me back to the mountains time after time for over 50 years.

The next day I made another foray into the snowy terrain hiking part way into White Chief Basin on the west side of the valley. I would revisit this area two more times after the snow melted away.

“Crows are not always available to give warning.” —Carlos Costaneda

I previously mentioned the shocking number of people who drowned every year along the Kern River. I soon learned that this phenomenon was not limited to that river. Memorial Day Weekend ten people drowned in the rivers between the Kern in the south and Yosemite Valley in the north. One of the victims waded into the Kawea River above the Ash Mountain and was immediately swept away. The next day I joined twenty other employees searching for the body. Our search failed to find the body. It turned up a few weeks later when the Spring melt slowed.

The first week in June I attended a week long Search and Rescue and Fire Fighting School. Fire fighting crews from all over the park as well as many seasonal rangers and maintenance employees also attended. It was clear that attacking fires was a high priority at the park. I did not realize at that time how much fire fighting would become a part of my life that summer. The uncredited stars of the training session were the seasonal Backcountry Rangers that I met. They ranged from 25 to 47 years of age. They all looked the part of the rugged mountain man and in one case woman. They exuded confidence. They would soon be flown into their backcountry stations where they would be masters of their domains for three or more months. I wanted to be just like them. (To learn more about these Rangers read The Last Season by Eric Blehm.)

“Whenever the laws of any state are broken, a duly authorized organization swings into action. It may be called the State Police, State Troopers, Militia, the Rangers… or the Highway Patrol.” —Narrator, Highway Patrol TV Show

The second week of June I finally began working as a Ranger out of my Ranger Station. My duties, in part, included law enforcement. I quickly learned that it was all to easy to loose one’s perspective when placed in a position of a law enforcement officer. If you are not careful you will fall into a “Us versus Them’’ state of mind. It is so easy to see everyone as a potential violator. Fortunately, I had received less than 20 hours of Park Service law enforcement training at this point. So, my indoctrination into the law enforcement world was incomplete and I avoided developing that mindset for the most part.

My work week was Friday through Tuesday. My primary duty was to patrol the section of the Mineral King Road that passed through the park. The road to Mineral King is a narrow (often only one lane in width), twisty route, 25 miles long. It begins two and a half miles north of Three Rivers, California. The road climbs up the East Fork Kaweah River Valley. After ten miles it reaches the Lookout Point Ranger Station (which is now an Entrance Station) at 4,019 feet.

The lower portions of the road passes through manzanita and brush covered slopes. Higher up the road passes through two groves of redwoods, the Redwood Creek Grove and the Atwell Grove. The Atwell Mill Ranger Station is located in the latter grove 19 miles from the start of the road. From Atwell Mill the road continued to climb through Silver City and to its end in the Mineral King Valley which was still administered by the Forest Service in 1974.

I was assigned a yellow one ton Ford Stepside 4WD pickup, with flashing red light on top of the cab, a siren, a big V-8 engine, a manual transmission and a slip-on firefighting unit in the bed. It was more of a fire truck than a law enforcement vehicle. The slip-on unit consisted of a large water tank, a pump and a hose reel and nozzle. The truck was big and heavy and a handful to maneuver on the steep narrow road.

The majority of the traffic on the road was destined for either Silver City or the Mineral King campgrounds, trailheads and private cabins. Silver City is a private inholding in Sequoia National Park located 21 miles up the road. It was first settled in 1858 by Hale Thorpe and his brother-in-law, John Swanson. In 1974 it was a summer time resort of maybe 30 private cabins as well as the Silver City Mountain Resort which encompassed a store/restaurant/grocery and a few guest cabins.

Although, there was always the potential of encountering law breakers, I seldom had to enforce any laws during my patrols. It was thought that just the presence of my vehicle would deter potential violators. Occasionally, park wide “All Points” bulletins would be issued to be on the lookout for dangerous persons. Fortunately, I never encountered anyone like that. I did respond to a few minor traffic accidents which involved conducting rudimentary investigations and completing accident reports. As a result of the steepness of the road cars often overheated. Road patrol duty mostly involved calling tow trucks for disable motorists.

At the start of my shift, I would checkin over the radio. The Park Service used the Ten-codes system to communicate over the radio. We were directed to use the codes as much as possible. The codes system was developed during 1937–1940 and designed to shorted time spent talking on limited the radio channels (which like a phone party line was used by many people). I had a list of the 100 codes the Park Service used taped to my dashboard. The most common and frequently used codes were easy to remember but you never knew when some by-the-book yahoo would go completely Broderick Crawford’s Dan Matthews character in the Highway Patrol television show and throw out a string of seldom used codes that I would have to decode.

My morning radio checkin would start with my code which was 106, followed by the code for “in service,” which was 10-8. A typical morning started as follows:

Me: “Ash Mountain, 106, 10-8, Lookout Point.”

Dispatch: “106, Ash Mountain, 10-4 (understood). If there were any messages, they would follow dispatch’s acknowledgement.

A typical conversation would be as follows—

Dispatch: “106, Ash Mountain, what is your 10-20 (location)?”

Me: “10-20, two miles west Silver City.”

Dispatch: “10-4, 106. 10-47 (assist motorist) midway between Atwell Mill and Lookout Point.”

Me: “10-4.” Upon arriving at the disabled motorist I would report to dispatch, “Ash Mountain, 106, 10-23 (arrived at scene), 10-24 (assisting motorist).”

Dispatch: “10-4, 106.”

After my morning checkin, if I was not directed to do a specific task, I would then take care of chores at the Ranger Station which included any minor maintenance, like mowing the small lawn or taking weather readings including high and low temperatures and fuel moisture which I would report to Dispatch.

I then started my patrol reporting to Dispatch “Ash Mountain, 106, 10-76 (enroute) to Atwell Mill.” The morning drive up the road was almost always uneventful. Arriving at the Atwell Mill Ranger Station, I would check in with the Atwell Mill Ranger, Stan and the Wilderness Permit Ranger, Larry and then continue up to Silver City or the Forest Service’s Mineral King Ranger Station. If it was a slow day that was my morning routine. Afternoons were alway busier with at least one car breaking down.

“We keep moving forward, opening new doors, and doing new things, because we’re curious and curiosity keeps leading us down new paths.” —Walt Disney

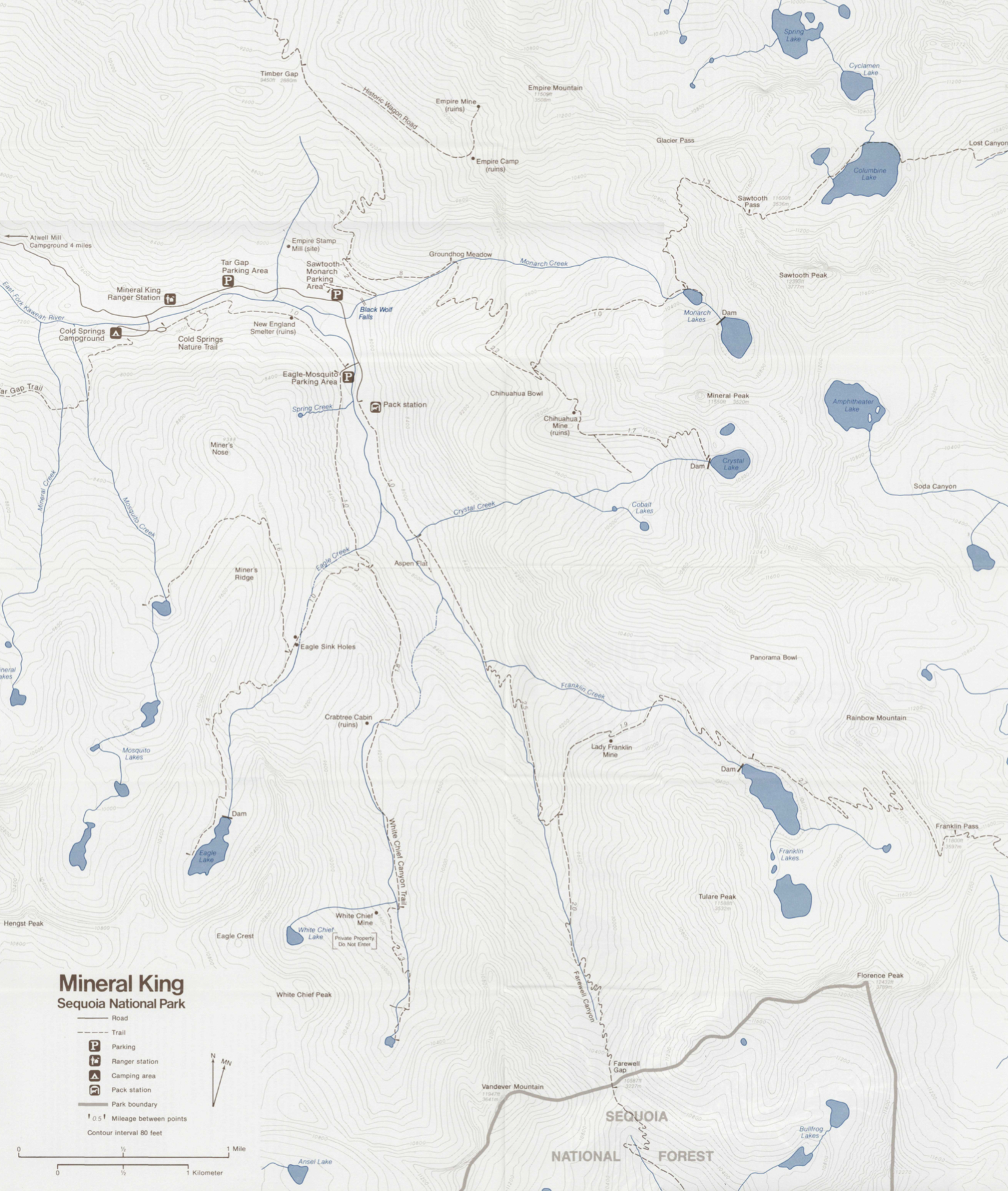

Mineral King is a subalpine glacial valley located in the southern part of Sequoia National Park. The valley is the headwaters of the East Fork of the Kaweah River. The Mineral King valley starts at an elevation of 7,500 feet and is over seven miles long and roughly a mile wide. The valley was carved by a long since disappeared glacier. The valley is surrounded by granite peaks which reach over 11,000 feet. The Great Western Divide forms the eastern wall of the Mineral King valley. This long divide separates the watersheds of the Kaweah, Kern and Kings rivers. Sawtooth Peak and Empire Mountain are two of the more prominent summits above the valley.

Silver was discovered in the valley in the 1870s. The influx of miners lead to the construction of the Mineral King Road in 1873. The original miners started one of the oldest communities in the Sierra Nevada Mountains to support the short-lived mining boom. The miners were responsible for the private property inholdings in the valley.

In the 1960s, Walt Disney Productions attempted to develop a Mineral King Ski Resort in the valley. Walt Disney had become interested in skiing around this time, and decided he wanted to build a ski resort someplace. He then chose the Mineral King Valley. The Sierra Club originally supported Disney’s proposal. However, as the project’s scope enlarged the Sierra Club changed its position and actively opposed Disney. In 1974 there was still a chance the resort would be built. Fortunately, the conservationist won and four years later, in 1978, the Mineral King Valley was added to Sequoia National Park.

“Everyone you will ever meet knows something you don’t.” —Bill Nye

One of the fringe benefits of working in a National Park is the opportunity to meet interesting people that you would other wise encounter. Throughout the Summer I constantly met interesting people including fellow employees, scientists and tourist. I still fondly remember two of these people.

J. Thomas Crowe, “call me Tom,” was a prominent Visalia, California attorney and a past president of the California State Bar Association. He had a cabin in Silver City. He stopped and introduced himself and his wife when he made his first visit of the year to his cabin. Every time I saw him that year he gave me fresh fruit or fish he just caught. He had an extensive knowledge of the Mineral King area’s history as well as its flora and fauna. One evening he had the Park Service crew over for dinner. He talked a little about practicing law. Many years later, when I was practicing law, I remembered something he said that night which I applied to my practice: “treat everyone in a case with respect and, win or lose, you are a winner.”

The second person of note was Jim Jenkins. I met Jim in September when he stopped by the Atwell Mill Ranger Station for a Wilderness Permit. In addition to his backpack he had a measuring wheel which immediately caught my eye. He explained he was collecting information for a guidebook and he used the wheel to measure trail distances. I invited him to stay at the station when he returned from his hike. On his return I barraged him with questions about making a living as an outdoor writer. He freely shared his expertise and reviewed my earliest attempts at writing magazine articles. I encouraged him to apply for a job with the Park Service which he did. The next year he worked as a seasonal Ranger at Mount Rainier. We became great penpal friends after that chance meeting. Jim wrote two guidebooks covering the Southern Sierra and co-authored two others. He also is credited with scouting the route for the Pacific Crest Trail through the southern end of the Sierra Nevada. Tragically, Jim was killed in a traffic accident in 1979. Mount Jenkins a peak on the Southern Sierra Crest was named in 1984. I credit Jim for starting me on my quest to become a guidebook author.

“It’s because I’m smarter than the average bear.” —Yogi Bear

One day I stopped for lunch at Silver City Mountain Resort. I was eating my lunch on the front deck when a car pulled up. Two guys got out. Based on their attire and disheveled appearance they undoubtedly had just returned from a backpacking trip. I greeted them, “how was your hike?”

“Good, Florence Lake was beautiful,” the first one replied. The second one, starting up the steps, looked up. Above his left blackened eye, was a large scab.

“What happened to you,” I asked.

“Bear!”

“Bear? A bear did that?”

“Yea, bear,” he said walking past me toward the store’s door. His companion had stopped, and was smiling looking at his friend.

“Wait,” I commanded. “If you were attacked by a bear, I have to write a report.”

“No, its okay, never mind,” he responded.

I moved in front of him and stopped him. “Seriously, I have to write a report.”

His friend was now laughing hard. He said, “Ranger you don’t understand. He wasn’t attacked by a bear. He was stupider than a bear.”

As it turned out, his friend was worried about bears getting into their food. To avoid this problem, he decided to hang their food from a tree. As he had read about this technique before the trip, he brought along a stuff sack big enough for their food and a long cord. He loaded the food in the stuff sack. He tied the cord around a rock. He found a branch that he thought would work perfectly and launched the rock skyward. The rock disappeared into the foliage. When the rock did not drop back down to the ground he turned to his friend and said, “maybe this isn’t going to work.” At that precise moment the rock fell and hit him on the head. “See,” his friend said, “you don’t need to write a report.”

“In my experience flying search-and-rescue missions, the greatest single variable contributing to successful rescues was the preparedness and expertise of the person(s) in distress.”

—Tom Gross

On the evening of June 25th. My work day ended at 6:00pm. I made dinner and about 9:00pm I walk outside to enjoy the cool of the evening. I looked up the canyon and spotted a fire burning. I reported the fire to Dispatch and the Atwell Mill Ranger, Stan. Stan was a high school teacher and coach in his early 40s. He was in incredible shape. He often boasted that his resting heart rate was the same as is age. Years later I saw the movie The Great Santini staring Robert Duvall cast as a tough-as-nails marine fighter pilot. I immediately thought Duvall had modeled his performance on Stan.

Based on my observations we believed the fire location was somewhere close to the trail to Hockett Meadows. Stan, Larry, the Ranger who issued Wilderness Permits, and I were ordered to make the initial attack. I put on my fire shirt, grabbed my go-pack and drove to Atwell Mill. An hour later the three of us were trudging up the trail toward Hockett Meadows. Stan carried a chainsaw, Larry a shovel and a backpack pump. I carried a Pulaski, a can of gas and a kit for the chainsaw.

At the three mile mark we could see a reddish glow and smell smoke. A little farther along we encountered a man and two kids sitting next to the trail silhouetted by the glow from the fire behind them . “Look kids, I told you, Rangers,” the guy said. The two kids simultaneously yelled “Yea!”

Stan, as the senior Ranger, asked “What are you doing here?” Larry and I continued to scene of the crime where we found a large campfire burning in the middle of the trail as well as several nearby downed logs burning. I called Dispatch and reported that we could handle the fire. Larry and I started throwing dirt on the burning logs. Stan arrived, complaining that he had carried a chainsaw that wasn’t needed.

“What was their story, Larry asked. Stan shook his head and chuckled.

“The pilgrims tell me they were lost and started the fires to bring rescuers.”

“Well, I guess it worked,” I said. It took us an hour or so to smother the flames with dirt and the three gallons of water Larry had carried in the backpack pump. Protocol required one of us to stay on site for at least 24 hours. I volunteered since the next day was my weekend and I would earn overtime and hazard pay for the duration of my stay.

Stan and Larry left a little after 1:00am, walking the three hapless hikers out. The next afternoon, at 3:00pm I reported to Dispatch that all the burned areas were cool to the touch. Soon there after I was told I could leave the burn.

I learned later in the summer that you can seldom trust a fire to be completely out. I was out with Greg, a Helitack crew member, during a particularly busy fire time. We had just finished sitting on a small lightening caused fire on Dennison Ridge that we had extinguished for 24 hours earlier. The helicopter picked us up. The pilot told us he was going to drop us on another fire. He flew us over the new fire. It was another small lightning caused fire on a forested ridgeline. The pilot started to look for a spot where he could land. The closest he could land was a couple of miles from the burning snag.

Bell 47 helicopters were essential to park operations. They were used to transport personnel to the backcountry, to fires, to search areas. The pilots were all Vietnam vetrans.

We hiked down the ridge, arriving at the fire around dinner time. After locating a good place to camp we made our way down the rocky spur ridge that led to the promontory where a single snag was slowly burning. It was roughly 100 yards away with a couple of little sections Class 3 climbing terrain to cross. It took us about two hours to put the fire out. We returned to our packs to eat. The light faded. We climbed into our sleeping bags. I quickly fell asleep.

Sometime in the middle of the night I woke up. It seemed awfully bright for the middle of the night. I sat up. It was bright because the snag was burning harder than when we had arrived. I woke up Greg and we made our way back down to the snag. Once again we stopped the flames. Suddenly, it was pitch black on a cloudy night. We had left our headlamps back at camp. It took us a long while to find our way back to our sleeping bags.

“News used to come too late; now it comes too early.” ― Marty Rubin

In 2020 it is hard to comprehend a time without the instant connection to the world provided by the internet and cell phones. In 1974 in the Sierra Nevada I gathered news via a transistor radio and five minute news summaries each hour on a local radio station. At night when I was at the station, I could pick up WKNX News Radio out of Los Angles. I had no television and rarely managed to pick up a newspaper. 1974 was a momentous news year. In February Patty Hearst was abducted by the Symbionese Liberation Army. In May President Nixon was named as an unindicted co-conspirator in the Watergate burglary and Patty Hearst joined her captors and helped rob a bank. When July rolled around the U.S. House of Representatives started the impeachment hearings that would lead to Nixon’s resignation in August. In some ways it was a news junkie’s worst nightmare. Based on the last four years of the political craziness emanating from the Whitehouse, I now see it was a blessing that I was out of the loop.

“It is one thing to decide to climb a mountain. It is quite another to be on top of it.”

—Herbert A. Simon

July 4th fell on my days off. I was somewhat disappointed because if I had worked I would have been paid double time. As a seasonal employee I had two goals. One goal, to explore as much of the park as possible, was aspirational. The other goal was practical, to make as much money as possible so I could survive unemployment after my assignment ended. The two goals often conflicted but for the most part making money had to take precedent.

Hoping to make the best of the situation I decided to attempt the most impressive peak surrounding Mineral King, Sawtooth Peak 12,343. I hiked into Monarch Lakes and set up camp. I then continued on to the summit of the peak. Unlike my previous visit to Sawtooth Pass, the snow was completely gone. From the pass I made my way up to the summit climbing over granite blocks on an ever steepening ridge. I found two climbers on the summit, one of whom, was using the lofty perch as a porta potti. “When you got a go, you got a go,” he explained. Needless to say, I didn’t spend much time on the stinky summit. I down climbed to my camp. I did not see another person for the next 24 hours. Amazing, considering it was the busiest tourist day of the year.

“No one has ever successfully painted or photographed a redwood tree. The feeling they produce is not transferable. From them comes silence and awe.” —John Steinbeck

On July 8th I ended my shift at Atwell Mill. I radioed Dispatch “Ash Mountain, 106, 10-42 (off duty).” Taking advantage of the long June days, I decided to take an evening hike. Two trails leave the station both cross through stands of giant sequoias. The Hockett Meadow Trail drops down and crosses the East Fork of the Kaweah River and then climbs uphill on its way to Hockett Meadows traversing a portion of the East Fork Grove. My hike this evening took me through the Atwell Grove to the summit of Paradise Peak, 9,362 feet. Although these two giant sequoia groves are less well know than the more accessible and famous Giant Forest grove, they offered something that grove can no longer offer—solitude.

Paradise Peak is a minor summit by Sierra Nevada standards but nevertheless an important peak. The Paradise Trail climbs north from the Ranger Station up to the top of Paradise Ridge and then drops down into the Middle Fork Kawea River drainage. At the top of Paradise Ridge a trail runs west to the summit of Paradise Peak. The world’s highest altitude giant sequoia grows near the summit. Surprisingly, the trail was seldom used in 1974 and, is evidently no longer maintained in 2020. My solo evening hike through the big and remote trees was magical. The view from the top included Castle Rocks.

One of my more memorable hikes was a ridge traverse from Timber Gap to Sawtooth Pass crossing over Empire Peak.

Although the crowded areas of the park were less intriguing, I did spend one of my days off dong the tourist thing, a visit to the popular Giant Forest area. Along with a crowd, I stood in awe below five of the world’s most massive trees including the General Sherman tree, the world’s largest tree. I hiked to the top of Moro Rock, a 6,725 foot granite dome on the 400-step stairway built by the Civilian Conservation Corp in the 1930s. Finally, I took a tour into the depths of the Crystal Cavern a marble cavern with a half-mile loop trail navigating the underworld.

“Not all who wander are lost.” —JRR Tolkien

July 17th, a day off, dawned as a bluebird day at Lookout Point. I quickly packed, hopped in my Gremlin and headed for Mineral King. My goal was to explore the southwest side of the valley. There was no early morning traffic and I quickly reached the roads end.

The basins on the west side of the Mineral King Valley were off the beaten path. This side of the valley included from east to west White Chief Canyon, Eagle Canyon, Mosquito Canyon and Mineral Canyon all topped off by the White Chief crest. Access to these basins starts at the end of the road where the White Chief Trail begins. The trail first passes Spring Creek which, true to its name, originates from an impressive spring just above the trail. There is a lot of water soluble marble interlaced with the upper Mineral King valley’s granite. The marble contains many caves which harbor underground streams.

I followed the trail as it climbed up the west side of the valley through the forest for a mile to a junction with the trail to Eagle and Mosquito Lakes. I turned on to the Eagle Lake Trail which climbs up Eagle Canyon to Eagle Lake. At one point, Eagle Creek disappeared into a sink hole. I came to another junction. This time I took the left fork. Soon after the trail crossed a boulder field I arrived at Eagle Lake. The lake was originally a naturally formed feature. However, it was dammed in the early 1900s by the Mount Whitney Power Co. to increase its water storage capacity.

After a snack break, I climbed south to the col on the White Chief crest above the lake. This granite ridge backdrops the White Chief, Eagle Lake, Mosquito Lakes, and Mineral Lakes cirques. It contains a number of high points. Once on the ridge I turned southeast, following the ridge to White Chief Peak, 11,159 feet. I then reversed course, hiking the ridge crest west to Hengst Peak, 11,146 feet and then continued north to Peak 11032.

I could not find a reasonable route down to the Mineral Lakes basin, so I reversed course and detoured to the top of Miners Ridge a minor 10,823 summit. Sitting on the summit of Miners Ridge, I surveyed another feature the Eagle Crest. Eagle Crest looked much more impressive from this vantage point than it had earlier from the White Chief Peak area. Its north ridge looked steep but doable. The longer I looked at it the more I was drawn to it as a possible way to descend back to the trail. Although I was tempted to try it, common sense prevailed. It was late. I decided to leave it for another day. I exited the ridge by the same route I used to climb it.

“Time is relative; its only worth depends upon what we do as it is passing.” —Albert Einstein

In July visitation increased dramatically. All seasonal Rangers were put on standby in anticipation of the need for search and rescue operations and backup firefighting duties. I had my go-pack ready at all times. My go-pack was a Sacs Millet rucksack, with a sleeping bag and pad, fire shirt, rain jacket, hardhat, flashlight, food and water. It was a minimalist set up. I often wonder why when I take a trip in 2020 why I need to take so much more gear.

Basically, in July, I would work my regular work week and then on weekends I would be sent out on a search or a fire. The overtime and hazard pay were great but it made the last two weeks of July morph into a long ordeal. It started at 6:30pm on July 17th. The phone rang. I was directed to take part in a search and rescue operation.

A hiker was reported missing in the Hockett Meadow area. Other than a copy of his Wilderness Permit, locating the hikers car at the Atwell Mill Trailhead and his wife’s statement that he liked to “get off the beaten path,” there was no other information to help narrow the search area.

The original call was received at Ash Mountain late in the afternoon. By the time the search was organized it was getting late. I was told that a helicopter would picked me up at 7:00pm. I had thirty minutes to get ready. I dug through a box of Army rations, picking and choosing the “best” of the “worst” and stuffed four days of the so called food in my go-pack.

The park seemed to have an unlimited store of Army rations. Every time I drove down to the Ash Mountain headquarters the fire office would give me a box or two filled with inedible delights. I actually could have saved money and eaten only this free food. Fortunately, I didn’t and lived to tell this story.

K-rations were developed as part of the Second World War effort as an individual daily food ration for the United States Army. The rations were intended as a food to be used only for short durations. The main course consisted of a 4 ounce can of beef stew or chili or some similar meet and potatoes dish. There were crackers and cheese packets to act as an appetizer. A can of fruit cocktail or cookies might be included as a desert. A P-38 can open was also found in each box. While working with the fire crew at Redwood Mountain, I was advised that because there was an unlimited supply, to pick the semi-edible food out of each box and throw the really bad stuff in the trash. When I brought a new box home, I looked through the trove for fruit, canned pound cake or cinnamon rolls, and canned main courses like beef stew or ham or chili. Needless to say, a lot of unopened cans were discarded.

The helicopter arrived on time and carried me up the mountain toward the search area. I was dropped off along with a member of the Helitac Crew at the backcountry Hockett Meadows Ranger Station. The Hockett Meadows Backcountry Ranger was already out searching on horse back. The Helitac crewman was assigned the task of hiking the trail back to Atwell Mills. I was directed to make a loop through nearby Sand Meadows.

I made the loop through the Sand Meadow and returned to the Ranger Station. The search so far was fruitless. After a brief radio discussion, I was directed to patrol from the Ranger Station west to Cahoon Rock, 9,236 feet. A 2.8 mile trail hike with minimal gain led to the unused fire lookout on the summit. From Cahoon Rock, I was told to search the Cahoon Meadow and Evelyn Lake areas. It was late and I knew any searching after Cahoon Rock would have to wait until the next day as it would soon be dark.

If the hiker was not located I was tentatively assigned to search the old trail from Evelyn Lake to Lookout Point. I imagined those directing the search at Ash Mountain standing in front of a big map, moving around magnets representing the searchers. They saw a trail on the map allegedly traversing the canyon from the lake to Lookout Point and decided it should be searched. I knew something the search coordinator didn’t know. The trail no longer existed and it was unlikely that anyone would be desperate enough to attempt a traverse through the brushy, snake and poison oak infested terrain. My assigned search area covered an immense section of rugged country. I thought they either have a lot of confidence in my abilities or they were curious to see if I would actually follow the nonsensical portion of my orders.

While it was highly unlikely that any hiker in their right mind would try to hike from Evelyn Lake to Lookout Point, even out of desperation, I desperately wanted to secure a full time Ranger position. Thus, I believed successfully completing all of my assignments was mandatory. Rather than pointing out to the search coordinator that searching the nonexistent trail was of a Fools Errand, I decided the best course of action was to take it one step at a time. I hoped the missing hiker would be found before I had to question to my orders.

I started for Cahoon Rock Lookout around 8:30pm as the long Summer day transitioned to night. The trail to Cahoon Rock was lightly used and poorly maintained. My headlamp, powered by four D sized batteries, quickly started to fade. I had packed in a hurry and not changed the batteries. Now in near total darkness, I forged on to the unmanned lookout.

Hiking in the dark is as exhilarating as it is potentially hazardous. I moved slowly. When the trail tread was somewhat less than obvious, I would momentarily turn the headlamp on, using the last bits of power. Eventually, I made it to the lookout. It was too dark to continue the search. I called Dispatch, gave my 10-20 and signed out. Dispatch confirmed my status.

It was time to put the sleeping bag down. I didn’t have a key for the lookout. Walking into a stand of pines looking for a flat spot I disturbed a screech owl which in turn startled me with a piercing screech as it flew past my face. It took a while to for my heart rate to slow down. When it did, I spread my ensolite pad and sleeping bag on the ground and ate a cold four once can of beef stew.

At this point, sleeping on the ground was second nature. Who could have guessed that my first night sleeping on the ground, would be followed innumerable nights sleeping on the ground. My first night on the ground was only notable for spending the night shivering.

After my stint in the Cub Scouts, I graduated to the Boy Scouts. I joined Troop 60 with my neighbor Bill Bobier. At the first Tuesday meeting I learned the Troop’s next camping trip was planned for the following weekend. I was a tenderfoot scout without any camping equipment. On Wednesday evening I asked my Mom if she would buy me a sleeping bag. She said “sure, we will get one tomorrow.” The next day after she got off of work late we drove around town. Most of the stores were closed and the stores that were open were not selling sleeping bags. We returned home. She called friends and relatives trying to borrow a sleeping bag without success.

My Mother was a MacGyver type character, a jack of all trades. There was no problem that she couldn’t find a resolution. She once repaired a broken clothes dryer bearing by substituting a lipstick container for the failed bearing. When I woke up Friday morning she had fashioned a sleeping bag out of blankets, sheets and safety pins.

I drifted off to sleep on the summit of Cahoon Rock marveling at the lights twinkling way off in the valley. At first light I called Dispatch and signed in. I ate a can of fruit cocktail, packed up and then made my way down to Cahoon Meadows. I could not find a trace of the trail from the meadows to Lookout Point. I was preparing to call Dispatch and plead my case that there was no point in attempting the search in that direction, when I received a call reporting that the hiker was found. “Whew!” I was relieved. I walked back to Hockett Meadows once again crossing over Cahoon Rock. An hour after I reached the Ranger Station, the helicopter picked me up and flew me back to Lookout Point.

“Thunderstorms were rare in California, but when they came they were, like most things in California, larger than life.” —Helen McCloy

The day after the search, a series of monsoonal thunderstorms erupted over the park. The lightening storms ignited numerous fires. When the first storm hit, I was in Visalia, California on a day off shopping for groceries. Visalia was the nearest big town and I often drove there to buy supplies. The weather over the mountains was unstable when I left Lookout Point but when I drove out to the valley it was hot and hazy.

When I came out of the grocery store it was raining. A thunderstorm had erupted over the Sierra Nevada and then swept down into the valley blowing away the haze. Looking west I was amazed. Homers Nose, a huge granite dome near Lookout Point, was struck by a lightning bolt at that instant. The strike was not what amazed me. I was amazed because I could see Homers Nose. In all the times I had visited Visalia due to air pollution I had never viewed the mountains from that vantage point. Now, that the storm had cleared the air I saw the Sierra Nevada as they had looked to the early inhabitants.

In the afternoon of July 23rd, two days later, I received a call from Dispatch and orders to go out on a fire. I returned to Lookout Point and grabbed the go-pack. Thirty minutes later a helicopter landed at the station. I climbed on board with the pilot. We were soon flying over the Paradise Fire which was the biggest fire I took part in 1974. I wondered why I was needed since the fire appeared mostly out as we circled over it.

My ride departing for its return trip to Ash Mountain. Getting dropped off in the middle of nowhere engendered mixed feelings of loneliness and excitement.

I was dropped off on a knob well above the fire and had to find my way down to the fire through thick woods. I joined a crew of eight. It was a reunion of sorts as five of the eight were from the crew I worked with on Redwood Mountain. The fire was in mop up mode. I was sent to relieve two helitack crew members. All in all, I spent two days helping mop up the five acre fire that had burned slowly in heavy timber at roughly 9,500 feet. This job involved putting out hot spots. The experience was certainly not what I expected. Although the fire was contained the fire boss waited another day to report the fire’s status. This insured we got additional hazard pay. The work was hard at times but never hectic or dangerous. Two days later I was released. We had to hike out to a road above Ash Mountain where we were picked up and driven back to Ash Mountain. My boss drove me from there back to Lookout Point that evening. This fire was the beginning of a two week period that took me to three additional small lightning caused fires.

“Yellowjackets—wants your food and will fight for it —never leaves you alone —will sting just for the hell of it -is just an a**hole.”

—Giedrė Vaičiulaitytė, Boredpanda

In early August the thunderstorm season ended. Work became more routine. However, there we always new experiences like my first encounter with a Yellowjacket infestation. I got a crash course in the the way of the Yellowjackets early in the month when I stepped on a nest during a search and rescue operation. Yellowjackets are sometimes mistakenly called “bees” since they are similar in size and color to honey bees, but they are actually social wasps. They often build their nests in the ground taking over mouse burrows and other holes like those in decayed stumps. Their natural food consists primarily insects, fruits, flower nectar, and tree sap. However, as the summer passed the Yellowjackets were thicker than mosquitoes and their available food sources dried up. The hungry Yellowjackets became very aggressive. They started swarming and scavenging ravenously for food around people. Tom Crowe put out put out Yellowjacket traps at his Silver City cabin. The traps would fill up in a matter of hours. The simple task of eating a sandwich became impossible to do outdoors. The yellowjackets would swarm the sandwich and even bite your hand.

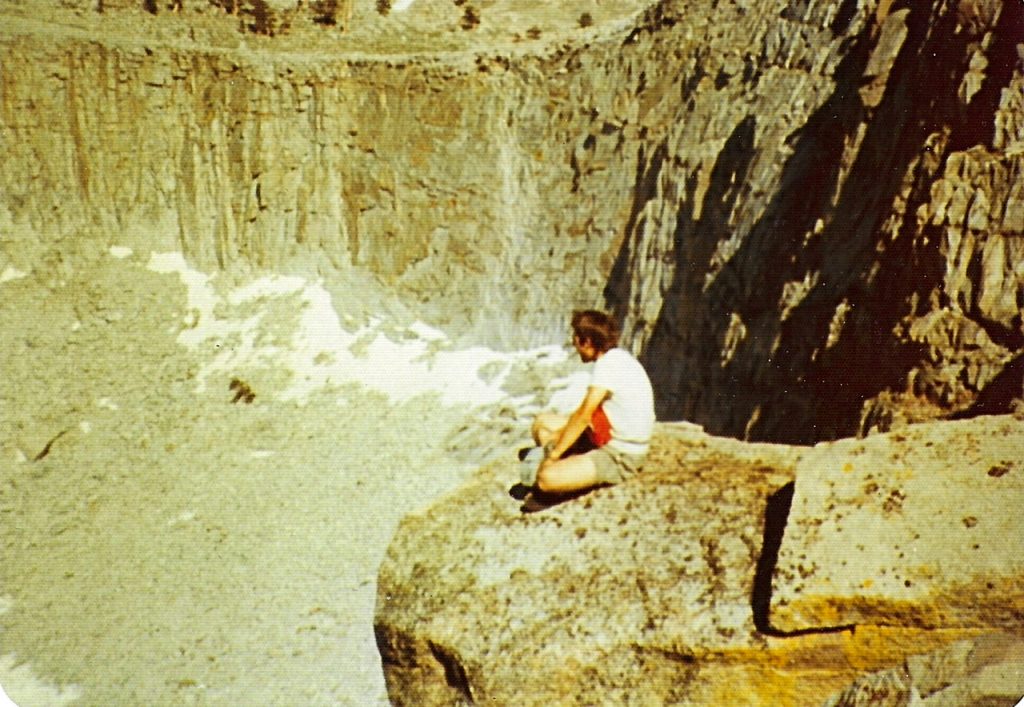

“I have no special desire to go crawl around in caves, but I really like the word [spelunking] and want to use it in conversation. I do a lot of things just to use words I like.” —Evan Mandery

On my first day off in August several acquaintances convinced me to join them exploring the White Chief Caves in Mineral King. There are at least 240 caves in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Even in 2020 there is not a lot of information available about the caves. In 1974 the only information available on the White Chief Caves was via word of mouth. Bill, the Sequoia National Forest Ranger, told us the location of the entrance and that it was possible to exit the cave farther down the mountain.

We found the opening where a stream was flowing into the mountain. We put on our hard hats and headlamps and entered the gash carved into the marble. The key, were told, was to follow the underground stream as much as possible. Soon we came to an impassable spot where the water disappeared under a wall. We moved to our right down a slanting hallway-shaped depression. At the end, there was a three foot wide by two feet high slot located at our feet.

After a short discussion which demonstrated that none of us knew what we were doing, we worked our way on our bellies through the slot. After ten feet, the slot opened into a larger room. We could hear the stream below us flowing through the chasm. We down climbed a short wall into this room. At the end of this room, we came to another blockage. About this time I began to realize that claustrophobia was overcoming my enthusiasm for this adventure.

The stream once again disappeared into the darkness. We located three possible exits from this small room. After a brief discussion, the middle exit was chosen. This opening was even smaller than the prior slot. We scooted through it on our bellies. Upon reaching the next larger room and finding more potential routes out of it. I decided I had enough. I knew I could find my way back out at this point. After a brief discussion, one of my three companions decided to join me.

We backtracked. I felt a weight off my shoulders when we reached the opening. The warmth of the sun, the blueness of the sky and the unlimited space of the White Chief cirque confirmed that spelunking was not a part of my future. Our two companions eventually found the exit and excitedly rejoined us. It was my first and nearly my last spelunking adventure.

Timber Gap is the lowest elevation pass leading out of Mineral King. A good trail leads to the pass.

“Rattlesnakes are only too plentiful everywhere; along the river bottoms, in the broken, hilly ground . . . if it can it will get out of the way, and only coils up in its attitude of defence when it believes that it is actually menaced.” —Theodore Roosevelt

Almost from the first day I arrived a variety of people warned me about the prevalence of rattlesnakes in the park’s western slopes. Since my time at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks I have encountered many rattlesnakes. There many different species and they all seem to have a different temperament. In my experience the western rattlesnake found in the Sierra Nevada mountains is the most aggressive. However, I’ve also learned over the years that these snakes are not as dangerous as most people think. They will avoid confrontations with humans if at all possible. You still must be cautious and alert in snake country but the odds are you will never have a serious run in with a rattlesnake.

The maintenance crew that opened up the Lookout Point Ranger Station told me that one day I would open up the sliding garage door and find a rattlesnake curled up just inside the door. It happened. They told me about a ranger who had been bitten by a big one near Ash Grove and had never fully recovered. The Ranger verified the story and warned me that the East Fork Kawea River was rattlesnake central.

One evening, I followed the trail from Lookout Point down to the East Fork and came across thirteen snakes in that short distance although only five of the snakes were rattlesnakes. During one search and rescue operation, looking for a missing fisherman, I hiked down to the East Fork following a use trail. It was over 100 degrees. At the bottom, we decided to take a break before making the steep, hot climb back to the Mineral King Road. I started to squat down to sit on a downed log when I spotted a rattlesnake snake crossing the log at the exact spot I was going to sit. Fortunately, it was so hot the snake could barely move.

The most interesting encounter occurred in September. I was directed to go to the private inholdings on the road to the Milk Ranch Peak Fire Lookout to check on whether a bear had broken into any of the private cabins. I found a pickup truck parked at the first cabin. The main front was open. I knocked on the screen door. All was quiet. I knocked a second time. No answer. I started for my truck. A big man appeared buckling his pants. He had no shirt on. I guessed he was taking a nap.

“Sorry to disturb you,” I said.

“What is it?”

Another voice, a woman’s called out from somewhere inside “who is it honey?”

I told him about the bear problem. Anxious to go back inside, he assured me he didn’t care. I said goodbye. I returned to my truck. As I started to climb into the cab, I heard the unmistakable sound of an agitated rattlesnake. I froze. I slowly looked around over my shoulder and spotted the agitated, coiled snake about eight feet away. Its menacing head was a big as my fist. Relieved at the safe distance, I momentarily debated whether to interrupt the cabin’s inhabitants again. I decided I should warn the big man. I returned to the screen door and knocked.

“Damn, what now?” I heard.

“Sorry, I just thought you should know there is big rattlesnake out here,” I replied.

“Okay, thanks a lot. See you!”

Then the woman’s voice again. “You kill that snake, or you not getting back in here.”

The big man soon reappeared, dressed this time. “Why don’t you kill the snake,” he asked.

“Its not in my job description and its too damn big,” I responded. I volunteered my shovel. He looked at me with disdain as he took the shovel.

“How big is it,” he asked as he walked around my truck. The snake immediately started to rattle. The area on the other side of the truck was an old apple orchard. The cattle that graze on this private inholdings had eaten the lower leaves and branches making a uniform overstory level at about five feet. The big man was at least six foot eight. He cautiously approached the snake leading with the shovel. Suddenly, he struck down with the shovel. He must have hit it with a glancing blow as the snake immediately sprung up skyward nearly reaching the bottom of the foliage. The big man nimbly jumped back and then savagely and repeatedly bashed the snake into a pulp.

“It was a big one,” he said handing me the shovel. “See you!

“It’s like summer wears the world out, and by October everyone is just ready for a nap”

―Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Water Dancer

By the end of the Labor Day weekend most of the seasonal Rangers had departed either to return to school or their real life jobs. The Sierra District departures that impacted me were Stan the Atwell Mill Ranger and Curt, the Hockett Meadows Backcountry Ranger. As a result, after Labor Day I moved up to the Atwell Mill Ranger Station in the redwoods.

The Atwell Mill Ranger Station is situated in the Atwell Redwood Grove a mile and half from Silver City. The station consisted of a beautiful cabin, a barn, a kiosk and a root cellar. The station also had electricity via a diesel generator. The Atwell Mill Campground was next to the Ranger Station. The campground area was logged before the park was established. A Judge Atwell originally owned the grove and he built a sawmill from which the stationed was named. Huge stumps of the trees the judge cut down remain in the campground. They date from late 1870s through the 1920s.

In addition to manning the Atwell Mill Ranger Station, my boss allowed me to make two long backcountry patrols through Hockett Meadows, one in September and one in October. The Hockett Plateau is a high, 8,500 foot land of rolling terrain decorated with lodgepole pine forests, gem-like lakes and most significantly beautiful sub-alpine meadows. It was wisely included in Sequoia National Park when the park was established in 1890.

My first patrol took place in mid September during a period glorious fall weather. I hiked in to the Hockett Meadow Ranger Station and then did day hike patrols from the station. The cabin was built in 1934 by the Civilian Conservation Corps. It was well built and maintained, a perfect setting for a budding Thoreau acolyte. I spent hours wandering around the plateau. I ran into a few backpackers. I asked them what they thought of the new wilderness permits system and walked on. I revisited the summit of Cahoon Rock, this time in the daylight. It was a delightful assignment.

My last climbing adventure occurred on my final two days off in September. I was determined to tidy up my unfinished business in the White Chief area—a climb of Eagle Crest. Larry joined me on the journey. We followed the White Chief Trail past the junction for the Eagle Lake/Mosquito Lakes trails. We kept left and continued climbing up through steep bluffs to reach the White Chief meadow which was full of flowers and the ruins of the Crabtree Cabin. The cabin dates back to the the 1870s. It was built by the discoverer of the White Chief Mine.

Above the meadows, the trail continued uphill to the remnants of the White Chief Mine. My plan was to reach the ridge crest above Eagle Crest and then descend down to the saddle on its south side, climb the peak and then descend its north ridge. We left the trail and climbed northwest above the mine and once on the ridge top turned south. Once on the White Chief crest we made our way along it to a point above Eagle Crest, 11,188 feet.

We descended down into the saddle between the White Chief crest and Eagle Crest. From the saddle the route to the top of the peak was an easy scramble that was made without issue. After a short break, We started down the north ridge. The next 1,600 feet of elevation loss was challenging and exhilarating crossing a lot of steep Class 3 terrain. At the bottom we rejoined the trail and made our way back to the trailhead. We had the golden aspens, the quiet forest, the high ridges and trails all to ourselves that day.

My second Hockett Meadows patrol took place from September 29th through October 2nd. The seasons were changing. The weather forewarned me of the upcoming Winter. It rained and the wind blew nearly the entire time I was on the plateau. The day patrols from the station in the brisk, damp weather were trying at times. There were no other people around. I was happy to hunker down in the Hockett Meadows Ranger Station each night with the wood stove fired up. It seemed the shorter days made those nights last forever.

The remainder of October was uneventful along the Mineral King Road. The weather was cool. Each day was a priceless gift in the crisp and quiet environment. The visitors were few and far between. The seasonal maintenance employees were gone. I spent an hour every other day maintaining the Atwell Mill Campground. I occasionally issued a Wilderness Permit. Otherwise I had the days to myself.

“There is no real ending. It’s just the place where you stop the story.” —Frank Herbert

The last week of October I was directed to close the station and move down to the dormitory at Ash Mountain. The days of my appointment were dwindling and dependent on the weather. There was not much to do at Ash Mountain besides maintain and store search and rescue gear. On October 25th I was sent to Cedar Grove in Kings Canyon to assist the one remaining Backcountry Ranger maintain a drift fence in Granite Basin. It was my last outing in the backcountry. Two days after I returned to Ash Mountain the first big storm of the fall slammed into the park dropping deep snow in the higher elevations and rain at Ash Mountain. The next day I was given my walking papers. After exploring new areas of the American West, hiking 310 miles, climbing 16 mountains, searching for lost and deceased visitors, fighting forest fires and playing law enforcement officer, the extraordinary Summer was at an end.

“Yes, my guard stood hard when abstract threats

Too noble to neglect

Deceived me into thinking

I had something to protect

Good and bad, I define these terms

Quite clear, no doubt, somehow

Ah, but I was so much older then

I’m younger than that now”

—My Back Pages by Bob Dylan

NEXT: New Zealand 1975