Kelly Lance, a 49-year-old endurance runner from Pocatello, climbed all of Idaho’s 12,000-foot peaks in a 119-mile, 78-hour push starting on September 2, 2017. Unlike the others who have climbed the 12ers in a single push, Kelly did it without resorting to mechanized transportation, the first traverse of its kind and perhaps the most over-the-top accomplishment on these peaks to date. This story is all about endurance, planning, training and determination but, in the final analysis, it is a story about a personal journey of discovery.

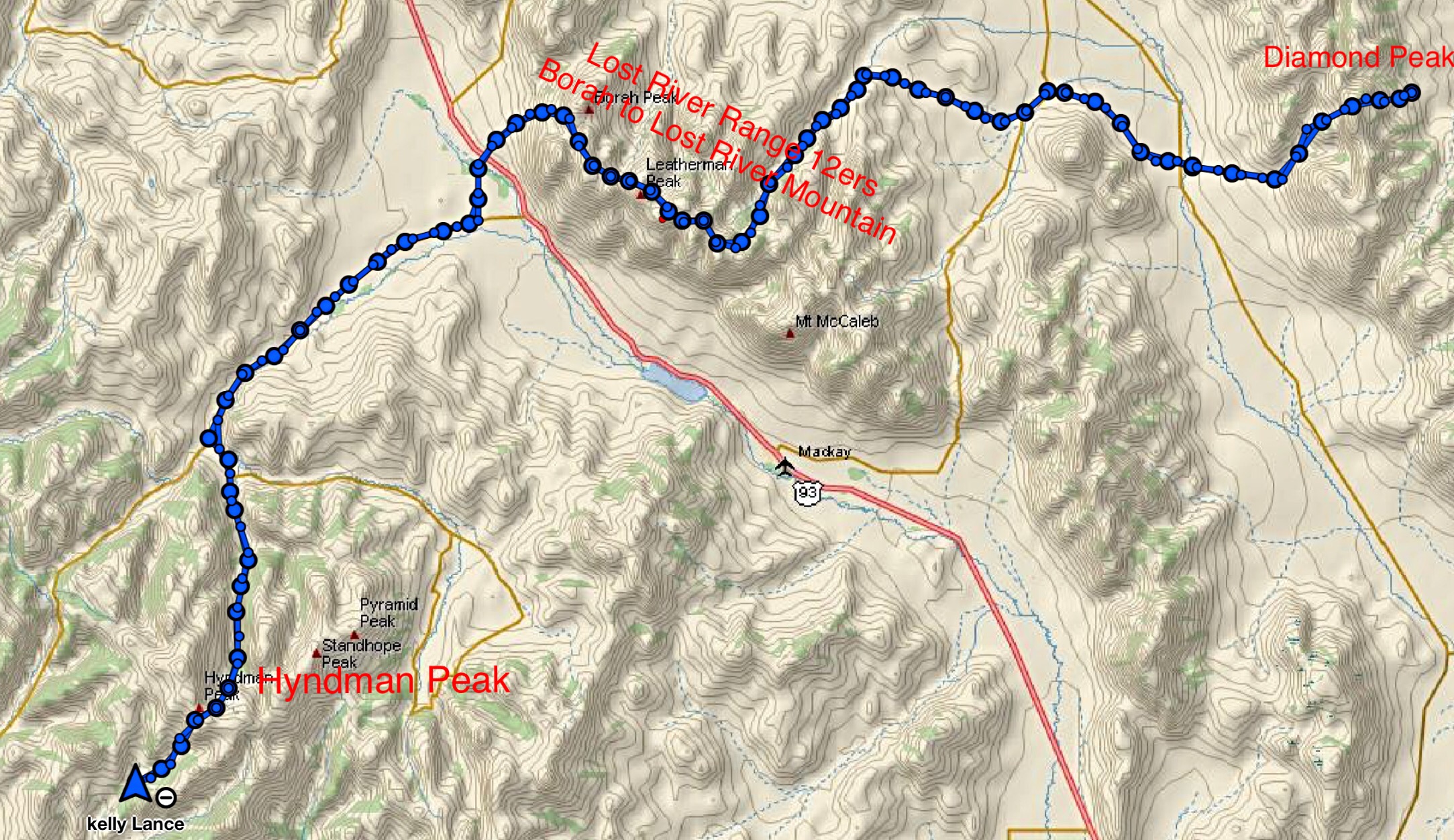

Kelly’s GPS track condenses his ordeal into a compact package. In reality his route was a sprawling journey.

What’s the big deal?

The 12ers are the 9 Idaho peaks that rise above 12,000 feet. Climbing these 9 peaks is considered a rite of passage for Idaho climbers. The 12ers include Idaho’s highest peak, Mount Borah, followed by Leatheman Peak (12,228 feet); Mount Church (12,200 feet); Diamond Peak (12,197 feet); Mount Breitenbach (12,140 feet); Lost River Mountain (12,078 feet); Donaldson Peak (12,023 feet); Mount Idaho (12,065 feet); and Hyndman Peak (12,009 feet). The 9 peaks are spread across 3 Eastern Idaho mountain ranges, with one peak each in the Lemhi and Pioneer Ranges and 7 peaks in the Lost River Range.

Climbers quickly discover that there is nothing easy about climbing these peaks. Each of the 9 peaks test a climber’s mountaineering skills, will power and conditioning. It takes most climbers several seasons to complete the list. While completing all 9 summits places a climber into an impressive and elite group of Idaho peakbaggers, climbing all 9 peaks in a single push without using a motor vehicle to travel between the 3 mountain ranges harboring the peaks is an accomplishment beyond the scope of mere mortal climbers.

The 3 fastest times for the 12ers are 1 day, 4 hours, 18 minutes by Luke Nelson of Pocatello and Jared Campbell of Salt Lake City accomplished in 2014 [1]; 1 day, 13 hours, 44 minutes by Cody Lind of Challis, Brittany Peterson of Boise and Nate Bender of Missoula accomplished in 2016 [2]; and 1 day, 14 hours, 50 minutes by Dave Bingham and Rob Landis of Hailey accomplished in 2006 [3]. All 7 of these record holders are impressive athletes. Luke Nelson and Jared Campbell are essentially professional, sponsored endurance runners. They all used vehicles to shuttle between the 3 mountain ranges and their times are impressive accomplishments. Kelly decided that the next step was to climb all 9 peaks by foregoing vehicle shuttles.

Kelly did it his way . . .

The seed was planted in Kelly’s mind during a conversation with his wife, Michelle. Kelly states: “…a couple years ago, some guys I know [Campbell and Nelson] did a fantastic job with the speed attempt. And kind of jokingly, I said, ‘Nobody’s ever done it without a car.’ Once I said it, I couldn’t get it out of my mind.” He continued, “I had to do it. I wanted a project that would put me out of my comfort zone. I was not a dedicated climber at the time. Attempting the 12ers without the use of a vehicle would, no doubt, put me out of my comfort zone and force me to become a climber.”

Using the standard climbing routes up each peak would require 8 separate ascents, as only two of the peaks are situated next to each other. Additionally, climbing each peak separately would significantly add to the overall distance and elevation gain. To overcome this problem, Bingham and Landis pioneered a route that linked together the 7 Lost River Range 12ers by staying as close as possible to the crest of the Lost River Range between Mount Borah and Lost River Mountain, thereby minimizing distance and elevation gain and loss. Keep in mind that the concept of minimizing elevation gain and loss are relative concepts in such an undertaking. Further, by attempting to stay as high as possible on the crest, Bingham and Landis and those who followed them had to face many other obstacles like cliffs, steep, loose talus slopes, lack of water, falling rock, and route-finding problems.

Planning is an essential prerequisite to success

Once the decision was made, Kelly jumped into planning his climb in earnest. Finding the correct route along the crest of the Lost River Range was the crux of the planning stage. He talked with Jared Campbell about his crossing in 2014 and with Lost River Range expert Wes Collins to get an initial understanding of the route. Most importantly, after tentatively planning a route, he climbed each peak to get a firm handle on the terrain he planned to tie together.

While other speed climbers traversed the 12ers from west to east, Kelly’s scouting convinced him the traveling from east to west would be more efficient. “Primarily, I recognized that to shorten the distance, I needed to traverse the two end peaks [Diamond and Hyndman] rather than following the routes used by the record holders,” Kelly said.

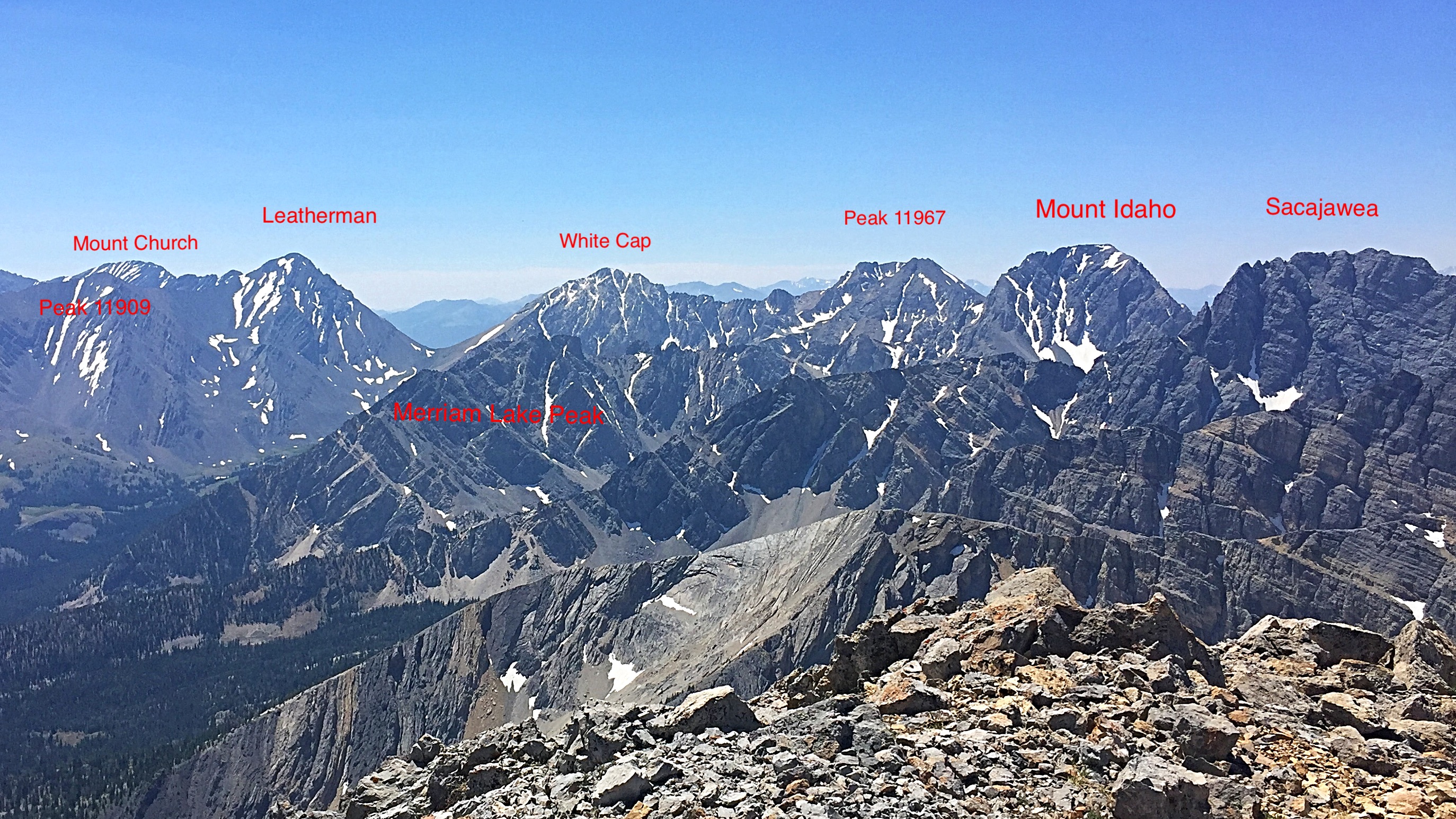

This photo shows perhaps the hardest portion of Kelly’s Lost River Range traverse from Mount Church to Mount Idaho but includes only 3 of the 7 Lost River Range 12ers. Tom Lopez Photo

Kelly also had to plan the logistics necessary to complete the odyssey. This included what equipment would work best, the amount of food needed to fuel his body, how much water to carry, and where and when to rest. “As an endurance runner with many long races under my belt, I had a good understanding of the logistical requirements but coupling this understanding with the mountaineering aspects required a lot of fine tuning,” according to Kelly.

Finally, Kelly lined up a support team he could rely on. His wife Michelle and daughters Charlee and Robbee were already enthusiastic supporters of the quest. Jack and Connie Oar volunteered to provide additional support after he descended Diamond Peak. Andy and Robyn Holmes and their kids joined the support team and Andy signed up to run with Kelly on a portion of route. Doug Lawton agreed to meet Kelly at Pass Lake, the midpoint for the second day’s route, and accompany him on his climbs of Mounts Idaho and Borah. So, with two years of planning under his belt and his support crew lined up, Kelly was ready to go.

Day One: A Diamond Peak east to west traverse and miles to go before . . .

Diamond Peak is the only 12er in the Lemhi Range. It is most often climbed from the east via a sharp, Class 3 ridge that has significant exposure in places. Class 3 routes involve actual climbing where your arms and hands are used to propel yourself up the slope. On September 2, at 10:30AM, Kelly said goodbye to his family and started up the mountain fresh and feeling strong. After traversing 2.5 miles and gaining 5,100 feet, he reached the summit at 12:50PM still feeling strong. One 12er down, 8 to go.

Kelly states: “Upon reaching the summit, I was in good spirits. Near the top, an immature Peregrine Falcon dove and landed 10 yards below me. I thought, the falcon was a good omen and even with the smoke in the valley, my plan would be fulfilled, or as Connie Oar said later, it was ‘good MOJO.’ ”

Now, Kelly set out on his descent. He was covering, based on his meticulous recon efforts, familiar country. He descended Diamond’s South Ridge toward the saddle between Diamond Peak and The Riddler. It is likely that fewer than a dozen climbers have ever crossed the South Ridge. From the saddle, his route turned west, dropping down steep slopes toward Badger Creek.

Kelly recalls: “My wife and I had previously traversed the peak during the recon stage. The descent into Badger Creek offered a little scree skiing but most of the distance involves crossing slippery rock slabs covered by scree. I didn’t want to rush the descent as I had several miles and hours ahead of me and so I slowed down. An injury this early would end my quest. I remember that I was in awe of the peaks around me realizing that the rock was once a sea bed. Down lower, the bushwhack made me glad I previously scouted the area with my wife. Further down the canyon, I began cramping when I stopped to refill water near the old miners cabins.”

Badger Creek empties out into the Little Lost River Valley, Idaho’s premier intermountain valley. The wide valley is characterized by sweeping alluvial fans, which have built up over the centuries as the mountains have eroded. This is high desert country, hot and dry. Kelly’s route took him across the Badger Creek Bar and continued down to the Little Lost River where he was greeted by his wife and kids and the Holmes and Oars. He remembers what a great feeling he had when he was greeted “with drums and noise makers.”

It was time for a break and a brief visit with the welcome committee while he ate, cleaned up, and prepared for the next section. From the river, his route continued along the East and North flanks of Hawley Mountain, a large, distinctive peak that projects eastward from the Lost River Range into the valley. Once past Hawley Mountain, his route crossed the broad, high plateau between Wet Creek and Dry Creek. This crossing involved steady but significant elevation gain.

Endurance running and climbing are often complicated by games that your mind plays on you, especially when you travel alone. This portion of the quest proved particularly frustrating. Kelly remembers: “My pace was slower than I hoped and I slowed to a walk at times. I think the unseasonably warm temperatures had something to do with, but it might have been that my first glimpse of the Lost River Range Crest was weighing on my mind. It seemed so far away.”

At 6:30PM, his family met him with their mobile aid station. The fueling stop turned into a good news/bad news incident. He ate a bit and drank a little and started running again. Kelly relates, “I promptly lost all the food I ate, but this actually made me feel better for awhile. Even though I was thrashed, I was once again able to maintain a steady jog. My spirits were low as the sun sank and the moon rose but the support of friends and family made me feel grateful. I realized they were making my quest possible.”

Kelly’s family had pulled a trailer into the Dry Creek drainage, the largest drainage on the East Side of the Lost River Range. He arrived at the camp shortly after 9:00PM. He relates: “I didn’t sit by the welcoming fire, instead I cleaned up and ate. I had originally planned on 4-5 hours of sleep at this stop. Funny, but plans and reality often clash. Sleep never came…cramping, anxiety, hearing every sound. I gave up at 2:30AM, upset and wishing I had just started earlier. I still didn’t have my pack ready for Day 2 and had to pack and eat. Behind schedule, I started out again at 3:45AM.”

Day Two: And now the going gets tough . . .

The first peak to be conquered on this day was Lost River Mountain. Kelly planned to ascend a seldom-used route that climbs up the peak’s treacherous East Face, the Northwest Gully/North Ridge Route, which is rated Class 5. In climbing terminology, Class 5 means roped climbing with the leader placing protection for the safety of both climbers. In other words, the route crosses technical rock climbing terrain usually ascended by a team using a rope for protection from falling. The route can be climbed by a solo climber but at greater risk. If this route was the only obstacle he faced that day, “It would have been an easy day,” Kelly thought.

It is a long way from Dry Creek to the summit of Lost River Mountain, as the drainage is massive. With this first difficult ascent of the day facing him Kelly started off, with Michelle and Andy Holmes running alongside of him, moving up into the incredibly scenic headwaters of Dry Creek. Kelly left his support team before reaching the headwall. Slowing on the headwall’s difficult rock he made his way up the climbing route without serious incident. He started to suffer nosebleeds and found that “trying to pinch my nose while climbing was a hassle.” Nevertheless, distance, lack of good trails, and the technical climbing obstacles, as well as the prior day’s effort and lack of sleep, delayed Kelly’s progress considerably. It took him over 7 hours to reach the summit, making it at 10:56AM.

It is likely that most climbers would have assessed their slower-than-expected pace, their physical output, and the difficulty of the route ahead at this time, and most climbers would have called it a day. But quitting did not cross Kelly’s mind. As an endurance runner, he has trained to put his mind into a Zen-like trance and continue on. The thought that did cross his mind at this point was an assessment of “How could I make up the lost time.”

After a brief rest, it was time to move on, and he started to descend Lost River Mountain’s North Ridge. Once again, this is not a traditional descent route. But Kelly knew from his recon trips and discussions with both Jared and Wes that staying on or close to the top of the ridge was a feasible route to Mount Breitenbach.

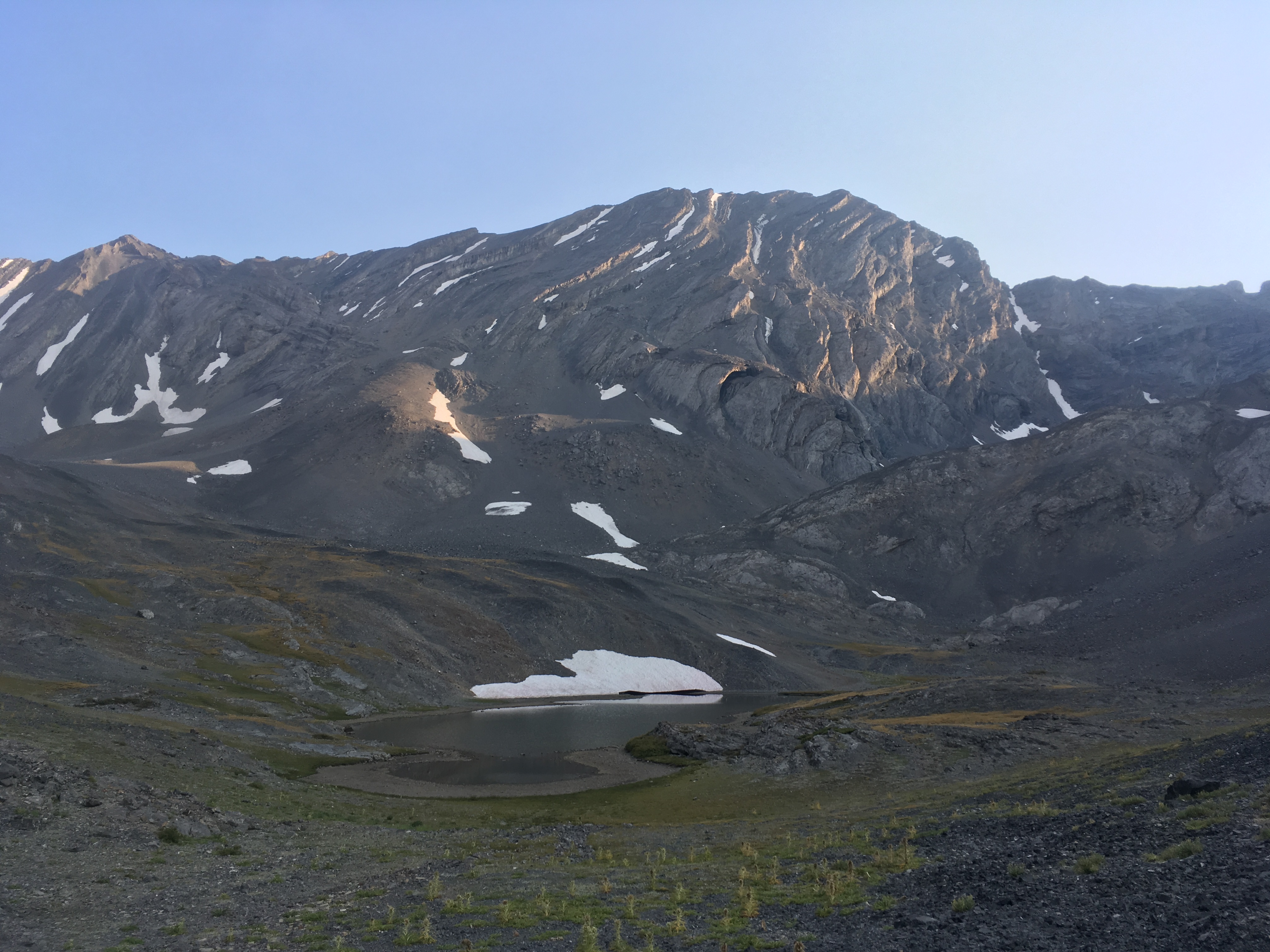

This photo of the Mount Breitenbach/Donaldson Peak Cirque shows the typical terrain found in the Lost River Range between Lost River Mountain and Mount Borah.

Rather than worrying about pace or quitting, Kelly recalls only focusing on the route ahead. “Being behind my ‘schedule,’ I was excited to see how fast I could maneuver along the difficult traverse of Breitenbach, Donaldson, and Church along the ridge. I was also contemplating a last minute ‘Plan B,’ which was to traverse the West Side of the crest after I summitted to get to Leatherman Pass. I knew this would take considerable time and would possibly delay me further, but I was a little nervous about the descent into the East Fork Pahsimeroi River. Based on my recon efforts, I knew the ramps I would have to descend from Mount Church would be covered with melting snow and ball bearings of rotten rock. I was taking a chance going this way, trading elevation loss/gain for side-hilling. A slip could have me rolling all the way to the Pahsimeroi.”

The first section of the traverse to Breitenbach took 2.5 hours but was uneventful. Kelly reached the summit around 1:30PM. Three 12ers, a third of the peaks were now climbed.

Crossing from Mount Breitenbach to Donaldson Peak was a different story, as the ridge top is barred by a series of cliffs and an intermediate peak. Knowing from his recon efforts that the ridge top was a non-starter, Kelly descended by dropping west off the summit into the rugged and unstable Upper Jones Creek Cirque. At 10,100 feet, he crossed to Donaldson’s East Face and started the steep slog up to the summit. He reached the summit after another 3 hours at 4:30PM. Four 12ers down and 5 to go.

From Donaldson’s summit, he was on familiar ground as he crossed over the convoluted Class 3 ridge to Mount Church. He quickly reached the summit after 45 minutes at 5:15 PM. This was the theoretical midpoint of his journey but, in reality, the most difficult terrain was still ahead of him.

From Mount Church, the Lost River Range Crest leading to Leatherman Peak is blocked by 11,953-foot Bad Rock Peak, a massive pile of broken cliffs, jagged ridges, and towers. In the planning stage, Kelly decided to bypass Bad Rock Peak on its East Side. This route took him down Mount Church’s North Face. He safely crossed the series of rugged ramps that had worried him as he aimed for an unnamed lake at 9,682 feet. He continued down the drainage past the lake until he could cross over Bad Rock’s Northeast Ridge.

Bad Rock Peak is a difficult peak to climb or circumvent at any time. Imagine facing it as the sun is setting with no sleep.

After reaching the bottom of the Northeast Ridge, he was in the headwaters of the East Fork Pahsimeroi River and had, figuratively, a straight shot up Leatherman Peak, which was due west. However, straight shots in the Lost River Range are never straight in reality. Loose rock, short rocky steps and massive amounts of elevation gain are always between the climber and his destination. So, all Kelly had to overcome from the point where he now stood was 3,700 feet of elevation gain over unforgiving terrain. The crossing from Mount Church took 4 hours. He arrived on the summit of Leatherman Peak at 9:15PM. He now had completed 2/3rds of the 12ers with only 3 to go. Another way to understand the energy output at this point is to recognize that since he left Dry Creek, he had been moving in difficult terrain for 17.5 hours after a short sleepless rest stop and after the prior day’s crossing of Diamond Peak and the Lemhi Range.

Kelly remembers: “Upon summitting Leatherman, the ranch lights below looked close enough to touch. The terrain was lighting up from the moon. Halfway down, I noticed the moon shadow of Leatherman was looming over Pass Lake. I probably could have traveled without a headlamp, but I couldn’t seem to get my night vision or depth perception when I would turn my headlamp off. It was mentally perplexing to move in these conditions.”

And now he had to descend, again losing hard earned elevation. He dropped down Leatherman’s North Face while aiming for Pass Lake, which sits in a cirque on the East Side of the crest below White Cap Mountain and Peak 11967 at 10,000 feet. Descending after a tough climb and on loose ground is never easy, and now Kelly was descending in the dark. Kelly notes: “In the dark, I didn’t descend far enough before turning west toward the lake and got caught up in a series of ribs and gullies that slowed my progress.” He arrived at the lake at 11:00PM where Doug Lawton was waiting.

Kelly was happy to meet up with Doug. Kelly remembers “Doug’s offer to meet me at Pass Lake was not pre-defined by a plan. I originally thought he could accompany me to Leatherman Pass if I needed him. At this point, part of me wanted to do the whole thing alone but when I met him, I was thankful he came.”

Kelly continues: “I asked Doug if he had a sleeping bag as I felt I was catching up on my schedule and I was running out of steam. I contemplated napping for a bit in our bivys but, after the previous night, I was afraid I would only lay there for a couple of hours, not sleep and lose time. I wasn’t in a frame of mind to realize the added fatigue and miles would have let me sleep just fine. In hindsight, I think I could have moved faster after a nap. So, with Doug joining me, we started out on the long night slog, first to Mount Idaho and then on to Mount Borah.”

Kelly’s chosen route on Mount Idaho would not be easy even for a rested climber. The route first crossed over Peak 11967’s ragged East Ridge, then dropped steeply down into the next drainage before climbing to the saddle on Idaho’s South Ridge, another big elevation gain of 3,000 feet. Kelly remembers: “The traverse below and to the saddle was slow, tedious, and time consuming. It was like I was stuck in a time warp. Slow rock hopping and not really any way to get into any rhythm other than a slog.” But Kelly and Doug persevered through the ‘time warp’ and arrived on the summit at 4:05AM.

Sacajawea Peak, a peak that is an even larger obstacle than Bad Rock Peak, stands guard on the Lost River Range Crest between Mount Idaho and Mount Borah. Based on his recon, Kelly recognized that the difficulty posed by Sacajawea’s ragged cliffs was best avoided. Thus he chose to drop off the West Side of the crest into the Cedar Creek drainage and traverse completely around the blocking ridge. He accomplished this task by descending Mount Idaho’s West Ridge to 9,800 feet and then dropped due north to treeline. At dawn, after moving steadily since leaving Dry Creek, he had been on the trail for nearly 27 hours. He stopped and slept for one hour.

Any honest person who has tested themselves against difficult physical task will tell you that staying focused in the moment and not second guessing is nearly an impossible task. As they stopped to rest Kelly remembers that he “Mentally would fall into a hole of wondering what I could have done different the past two days to be in a better position time-wise. Doug told Kelly, ‘Not to feed those thoughts,’ which helped me refocus and get through the rest of the morning.”

After this brief refresher, Kelly and Doug climbed due north toward Borah’s summit, still 2,800 feet above the resting spot and once again crossing difficult terrain. Those who travel in the mountains are occasionally rewarded with transcendental experiences. It was now Kelly’s turn. He relates: “After our nap, a group of ewes and lambs suddenly materialized in front of us on the ridge. From this point, Doug and I and the bighorns climbed together at the same pace as if the sheep were guiding us. When we stopped, they stopped as if waiting for us to catch up.”

After reaching the crest above Chicken-Out Ridge, they followed the climber’s trail to the summit, arriving at 11:15AM. Kelly now had 8 12ers down and one more (Hyndman Peak) to go. Kelly descended the well-beaten climbers trail from Borah’s summit to the trailhead where his support crew was standing by at 2:05PM.

Except for the one-hour nap in Cedar Creek, Kelly had been awake for 55 hours and it had been 34 hours since he left the Dry Creek stop. Kelly relates: “It took me 34 hours to run the Hardrock 100 in the San Juans and I still had to face Hyndman and completely cross the Pioneer Mountains. I really didn’t know what I would feel like after resting and was VERY unsure how I was going to complete the remainder of the trip. Lack of sleep had me worrying how to get my kids to school and wife to work the next day. I thought at the least, I would grab my backpack and just hike the remainder. Even though my mind was running wild, I fell asleep.”

Day Three: The end is just over that ridge up ahead . . .

Waking at midnight, Kelly relates: “I felt amazingly refreshed with the sleep. I thought I would start at a walk but I immediately felt like running. It felt good to be using a different gait and covering the relatively flat ground of the Big Lost Valley. For some reason, I had dreaded the thought of running the road. I guess I was transitioning from a runner to a climber after spending so much time in the mountains. Michelle told me the road miles would fly by and she was right. While I did walk periodically, I ran for the most part. The moon was a deep orange from the smoke-filled skies. I turned my headlamp off. The road’s center line, the moon, and a cold headwind was my world until dawn.”

Running toward that big orange moon, Kelly proceed downhill from camp, crossed US-93 and started running up the Big Lost River drainage on Trail Creek Road to the junction with Copper Basin Road still many miles ahead.

All that stood in his way was the final 12er, Hyndman Peak. After reaching the junction, Kelly’s route briefly followed the road toward Copper Basin to the mouth of Wildhorse Creek. Now, with only one 12er left, a kind of peace descended into Kelly’s mind. “I found my pace getting slower. It was so beautiful in the valley. For the first time, I stopped thinking about my time schedule and wanted to experience what I was going through. I stopped to eat a sandwich, drink from springs (even though I had water), look over the East Ridge of Hyndman and contemplate how it came to be.”

In mountaineering circles, the Wildhorse Creek drainage is known as one of Idaho’s most impressive locales. Steep, glacially-carved peaks surround this valley and Hyndman Peak lords over the upper reaches looking unclimbable to all but the hardiest climbers. Based on his recon and prior ascent, Kelly chose a route up the steep East Wall of the Wildhorse Cirque that climbs 2,000 feet up the North Face of Old Hyndman Peak to the Pioneer Crest, less than 400 hundred feet below Old Hyndman’s summit. Here, he turned north, dropped down Old Hyndman’s Northwest Ridge, and climbed up Hyndman’s South Ridge to the summit, arriving at 3:00PM.

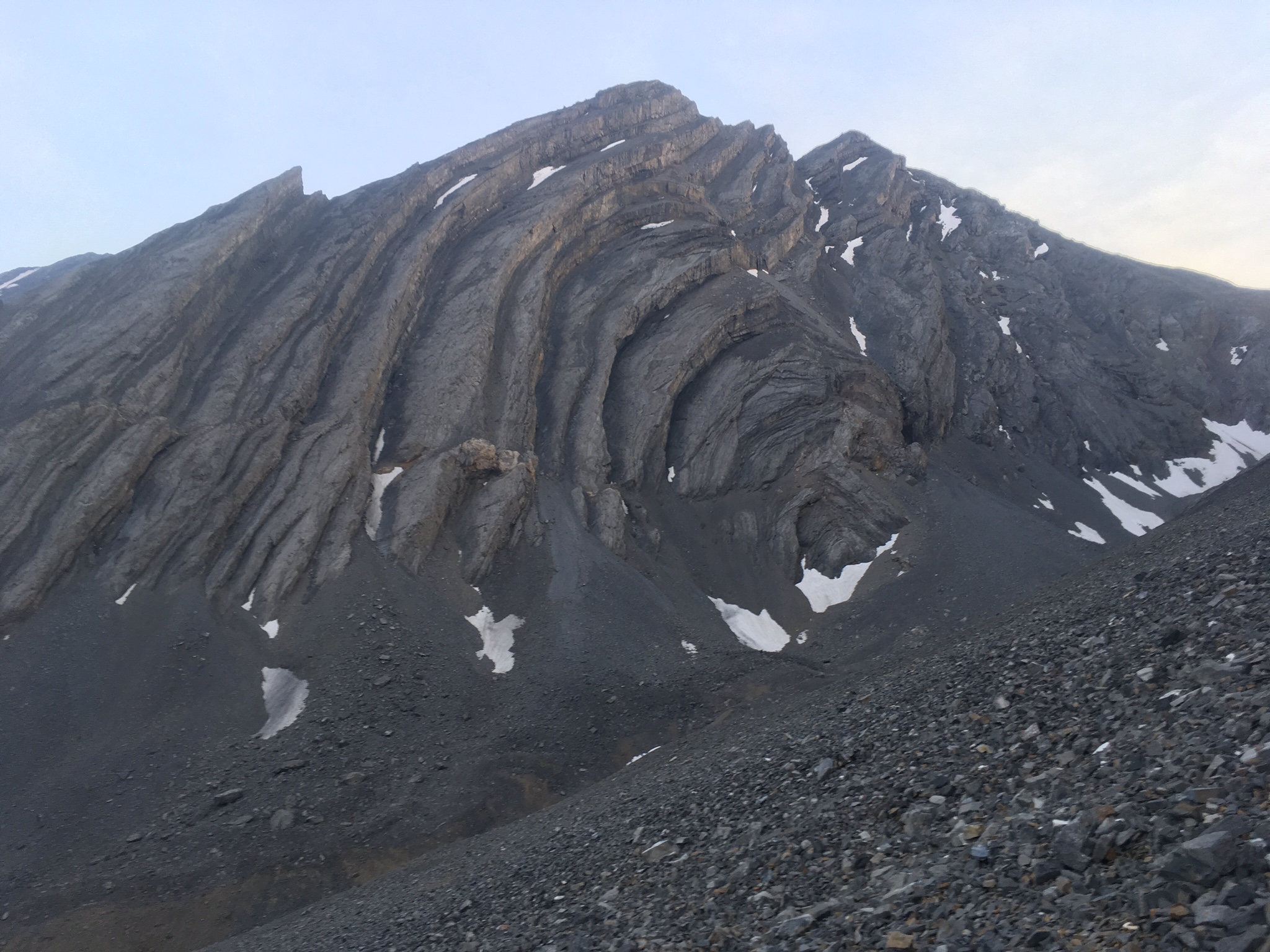

After running since midnight, Kelly still had to climb Hyndman Peak. His chosen route climbed up this steep, rotten rib on Old Hyndman Peak.

Once he topped out at the base of Old Hyndman’s summit block, he had to turn north and traverse this ridge to the summit of Hyndman Peak.

He still had the descent to the trailhead but physically, in comparison to the distance he had already traveled, that would be relatively easy. On the summit, Kelly turned on his phone and text messages immediately flooded his screen with messages of support. “I became pretty emotional,” he remembers, “not so much because of what I had done, but because the messages brought home the overwhelming support I had received over the last two years. It was pretty hard to hold my emotions back. Physically, I didn’t feel any pain. It was my mind that was finally relieved to get a break from the constant concentration that I was putting it through.” Kelly had now climbed all 9 12ers and only had the descent from Hyndman to the trailhead. Of course, the trailhead is 5,000 feet below the summit, so it was no easy task after already crossing over 100 miles.

Kelly dropped off the mountain heading for the trailhead at an easy pace. He recalls: “I started my descent off Hyndman. I did stop once to clean my shoes out and ‘soak it all in.’ I even slowed a few times to film, but my running pace was strong and I really didn’t try to hold back.” Nearing the trailhead, he let out a few yells and was promptly answered back. Then it was over. “I was greeted by my daughters, wife and dogs. I had to make sure to touch the trailhead sign. They had decorated the trailer with signs and flags. Michelle sprayed me with champagne. They all made it very special.” He arrived at the trailhead at 4:35PM.

No Man Walks Alone . . .

Journey and ordeal over, Kelly now traveled through an emotional reconciliation with the last two years. He asked himself many questions. “What now? Was it worth it? What could I have done differently? What did I accomplish? What do I do now?” The value of his effort was not immediately apparent according to Kelly. “Now I’ve had a few more weeks to think about my accomplishment, I feel all the time, effort, money, and physical pain, added value to my life. I always thought the end result would be the ‘worth it,’ but the reasoning has changed.”

Having completed the task, I found that the three days of suffering and completing a difficult task was not nearly as important as my completion of the entire task and the involvement of family and friends. It was the whole journey that really makes me proud.” Kelly continues: “The unfamiliarity of the route beforehand, the people I have met in the process, conversations, exploration, overcoming uncertainty coupled with the overwhelming support from my wife and family made me recognize that no man walks alone even when he is struggling solo up a difficult rock face.”

[A shorter version of this article was published in the Idaho Statesman.]

Statistics

· Day One: 32.1 miles; 6,522 feet of elevation gain.

· Day Two: 42 miles; 20,640 feet of elevation gain.

· Day Three: 44.9 miles; 6,603 feet of elevation gain.

Equipment and Supplies

Day One:

Diamond Peak trailhead to Bridget Creek

· Pack: Osprey Duro 15 pack. Fuel: 3.5 liters of water, jerky and gels.

· Clothes: Black Diamond gloves, Dry Max overcalf hiking socks, La Sportiva Ultra Raptor shoes, Gaiters–Wool First Lite.

· Poles: Black Diamond Carbon Mountain poles.

Desert run from Badger Creek to Dry Creek:

· Pack: Ultimate direction Anton Krupicka pack.

· Clothes: Changed shoes and socks. [to what?]

· Fuel: sandwich, chips and a Coke at first rest stop. Changed shoes and socks. gels and trail mix. Chicken and rice soup at second rest stop (vomited shortly thereafter). Coke (note ensure when done for the day) and mashed potatoes.

Day Two: Dry Creek to Borah trailhead.

· Pack and Misc. Gear: Osprey pack, two headlamps, emergency kit with lighter, first aid supply, and bivy sack, Aqua Mira water filter and a knife.

· Clothes: Wool gaiters. Outdoor Research rain jacket, wool T-shirt, wool long sleeve shirt, down puffy, Black Diamond gloves.

· Fuel: Eggs, cheese, and banana with coffee for breakfast. 4 L of water, Nuun electrolyte, Perpetuem drink by Hammer Nutrition. Two wraps with cheese and salami in flour tortilla, 30 gels, tuna fish, jerky, trail mix, couple candy bars.

Day Three: Trail Creek Road to Hyndman Peak to the Hyndman Creek trailhead.

· Pack: Ultimate direction Anton Krupicka pack.

· Poles: Black Diamond Carbon mountain poles.

· Clothes: Dry Max trail crew socks, Outdoor Research rain jacket, La Sportiva Ultra Raptor shoes

· Fuel: Several gels, eggs, and cheese at first rest stop, chicken sandwich, jerky. Coke at finish and ribeye steak and potatoes for dinner a couple hours later, with a beer.

Pingback: Ultramarathon Daily News | Thurs, Oct 12 | Ultrarunnerpodcast