ARTICLE INDEX

This Article was first published in the March issue of Idaho Magazine, Vol. 23, No. 7

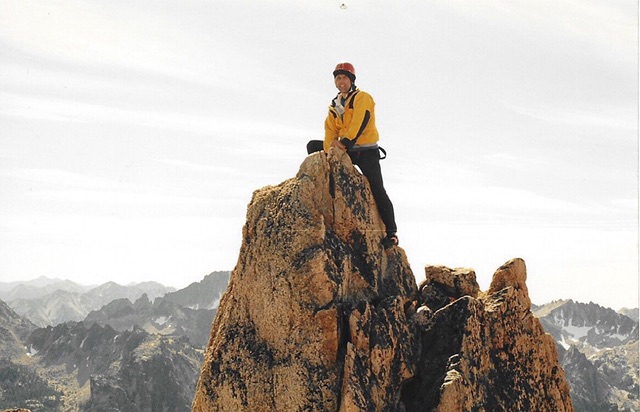

Mount Regan, Sawtooth Range

After Dana Hanson and I scrambled up the east ridge of Mount Regan, we encountered a smooth vertical wall blocking our way. We were fewer than thirty feet below the summit, but were ill-equipped to climb the wall. We had not expected that the route would require technical climbing and had not brought a rope. We sat catching our breath and considered our predicament. I often believe discretion is the better part of valor, but no climber wants to turn around on a beautiful day thirty feet below a stunning summit. Summit fever drives on many of us in the face of adversity. This day, I was in the grip of that fever.

After Dana Hanson and I scrambled up the east ridge of Mount Regan, we encountered a smooth vertical wall blocking our way. We were fewer than thirty feet below the summit, but were ill-equipped to climb the wall. We had not expected that the route would require technical climbing and had not brought a rope. We sat catching our breath and considered our predicament. I often believe discretion is the better part of valor, but no climber wants to turn around on a beautiful day thirty feet below a stunning summit. Summit fever drives on many of us in the face of adversity. This day, I was in the grip of that fever.

The Sawtooth Range needs little introduction for most Idahoans, who rank it asone of Idaho’s most important resources, along with the Salmon River and potatoes. Thebest-known of the state’s many mountain ranges, it’s also the ancestral home of Idaho mountaineering, where famous climbers including Robert and Merriam Underhill, Fred Beckey, Louis Stur, and Lyman Dye set a high standard. The eastern escarpment of thisrugged collection of granite peaks and alpine lakes is perhaps Idaho’s most impressive mountain backdrop. At least fifty peaks that exceed ten thousand feet in height are scattered throughout the range but many other spires and towers crowding the high ridges also present challenging climbs. The main Sawtooth Crest stretches more than thirty-twomiles from north to south and twenty miles from east to west, but when I think of the Sawtooth Range, two peaks immediately come to mind. The first is Mount Regan.

This stunning beauty likely has graced more calendars than any other Idaho peak,and its slopes have drawn climbers at least since 1934, when the Underhills and Dave Williams made the first ascent. When Dana and I made our assault in August 1986, wefollowed the Underhill route, which is a classic mix of broken rock talus, a sharp ridge,and a summit block so forbidding that the very sight of it makes you doubt your skills.

I looked upwards, searching for a way to ascend the wall, or more precisely, a way to get down if we made it up. At the far right side a narrow ledge skirted the walland possibly led to the peak’s north face. Gingerly, I stepped onto it and worked aroundto a larger ledge that did lead me to the middle of the peak’s north face. Dana followed. We were in a shady alcove. The rock above us was broken but still nearly vertical. To the north there was nothing but air. The drop was close to vertical, all the way down to Sawtooth Lake nearly two thousand feet below.

We did not feel confident. In fact, we decided to quit. But my mind stewed: “It’s a long way to come,” I thought. “I can climb this wall. It’s nothing I haven’t done before. Ignore the drop.” I faced the wall, shouted, “Dang,” and started up. Moments later, I was on the summit. The thirty feet of rock had looked bad mostly because a fall could be fatal. Dana made it to the top, too. Rank: 8.

Mount Heyburn, Sawtooth Range

Mount Heyburn is the second Sawtooth summit that pops into my mind when someone mentions the range. The mountain’s Stur Chimney is Idaho’s most classicclimbing route. It combines a beautiful approach via the Bench Lakes drainage with a two-pitch climb on solid granite up a crack that is a textbook example of an alpine chimney. Before Sawtooth legend Luis Stur found this chimney, a lot of famous climbers had summited the peak via grungy routes characterized by deteriorating granite. The SturChimney is one of those rare routes that are so enjoyable, they leave you speechless.

In 1996, a friend told me about Scott MacLeish, a competent technical climber who was seeking a partner to summit Heyburn. I was a little leery, because to share a rope on a technical climb requires mutual trust, which ideally comes from having climbed together before. Nevertheless, after a brief phone conversation, I decided to trust the recommendation of our mutual friend and agreed to join Scott.

In early October, we drove up to Redfish Lake, hoisted our backpacks loaded with climbing gear, and hiked to the Bench Lakes, where we camped for the night. The next day we were up early. We climbed out of the Bench Lake basin in beautiful weather and traversed south along Heyburn’s west face to the base of the route.

The lower route ascends several steep granite slabs. I would have preferred to rope up for this section but Scott scampered right up, so I followed him to the base of the Stur Chimney. We put on our harnesses, laid out the climbing gear, uncoiled the rope, and placed two climbing cams into a crack to act as our first belay anchor. We were ready but neither of us moved.

Finally, Scott said, “I’ll belay you.”

“This is your climb.” I responded. “I’ll belay you.”

“I’m not leading this climb,” he replied.

I wouldn’t say the discussion deteriorated from this point but neither did it resolveuntil at last I blurted, “ S#%*, put me on belay!”

Scott obliged. As I started up, I wondered if I could rely on his belay if I fell. But the climb proved easy, and placing protection was simpler than I could have imagined. The joy of ascending this perfect route was intoxicating and I silently thanked Scott for forcing me to take the lead. Soon, we were shaking hands on the summit. It was a true climbing high. Rank: 4.

Old Hyndman Peak, Pioneer Mountains

As a backcountry ranger for the Forest Service’s Ketchum Ranger District in 1979, I patrolled the western Pioneer Mountains, but climbing them was, unfortunately,not in my job description. I spent a lot of time that year staring at the range’s big three: Hyndman, Cobb, and Old Hyndman.

I’ve noted elsewhere that Idaho’s premier range by almost any measure is the Pioneer Mountans. Its peaks are high and wild, the rock good, the lakes gorgeous, and the vistas terrific. From east to west, it stretches nearly fifty miles between Ketchum and Arco, and it’s almost twenty-five miles wide. The Matterhorn-shaped Old Hyndman Peak is only the eighth-highest pinnacle in the range but when it comes to aesthetics, it’spreeminent.

In September 1990 I entered Big Basin on Old Hyndman’s southeastern side, accompanied by Dana, Mark Weber, and Basil Service. Our subsequent climb proved the axiom that sometimes the journey is as rewarding as the destiny. Numerous stands of aspen displayed their golden colors of fall, the route stair stepped its way up the pristine basin, and the peak’s southeastern face stood up defiantly, daring us attempt what seemed like its un-climbable upper wall.

We pressed on, confident that we knew the mountain’s secret: the seemingly difficult upper face is cut by a black rock dike that forms a protected staircase, whichsplits the nearly vertical three-hundred-foot section of the southeast face. There are a lot of challenging routes on Old Hyndman but none is as rewarding as the climb up the black rock dike. Rank: 9.

Mount Idaho, Lost River Range

It’s always been tough for me when the year reaches the edge of winter, because I hate to see climbing season for the big peaks come to an end. That’s why on the first weekend in November 1990, Dana and I finished work on a Friday and drove up to Basil’s home in Ketchum. That evening we carbo-loaded at an Italian restaurant and well before sunrise, we drove over Trail Creek Summit to reached the foot of Mount Idaho as the day was waking up.

The Lost River Range, Idaho’s highest mountain terrain, stretches seventy miles from northwest to southeast between Challis and Arco. The Big Lost River Valley and the Salmon River flank the range on the west, the Little Lost River and Pahsimeroi River along the east. The range contains not only the 12,662-foot Borah Peak, Idaho’s highest point, but also seven of the state’s nine twelve-thousand-foot peaks. Eighty of the range’s peaks rise above ten thousand feet, with twenty-eight “teners,” and forty-five eleveners.

It was a comfy five degrees as we left the truck and started the climb of Mount Idaho, one of the twelvers. Its variety of challenging terrain is memorable. The first part meanders up a steep canyon, and then it’s a steeper climb up a broad rib characterized by weathered trees and talus. Eventually, the route leads to an airy col or dip between Mount Morrison and Mount Idaho. Next is an exposed climb up the west ridge to an un-climbable vertical step. Not to be deterred, we followed a steep and narrow ledge onto the mountain’s southwest face. At the end of the ledge, we climbed a gully through early-season snow to the summit. There we encountered a steady 20 mph wind. To the north, a wall of clouds threatened to engulf the mountain later in the day. It was a great way to end the climbing season. Rank: 3.

USGS Peak, Lost River Range

The trail Dana Hanson and I hiked along Long Lost Creek in August 1990 had probably not been maintained in a quarter-century. Our destination was the eleventh-highest Idaho summit, 11,982-foot USGS Peak, unofficially named in honor of all the US Geological Surveypeople who mapped Idaho. Specifically, we were headed for the peak’s north face, which had never been climbed.

This was our second attempt at this Lost River Range summit, which is protected on all sides by steep walls and in many places by imposing cliff bands. Our first try, a month earlier, had stalled high on the peak’s northeastern ridge, where a cliff band and an approaching thunderstorm convinced us to turn around. On that day as we climbed, we had had a good look at the route we intended to take today up the peak’s snowy north face.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the north faces of high, once-glaciated mountain ranges often are characterized by vertical or nearly vertical walls. This is because snow ice is more likely to accumulate and form glaciers on shaded northern slopes. Eventually, this glaciationerodes the rock into steep-sided cirques, often the mountain’s most difficult terrain to climb.

The allure of north faces likely has its origins in the lore surrounding Switzerland’s Eiger. Its 5,900 foot-high wall of ice and rock is the biggest north face in the Alps, and long was considered the last great climbing problem in that range. The mountain was first climbed in 1858 but the north face was not conquered until eighty years later. By then, the face had earned the German nickname Mordwand (“murder wall”) as more than sixty climbers have died on it.

While the Lost River Range mountains are not the Alps, the range has four impressive north faces: on Borah Peak, Mount Idaho, Mount Brietenbach, and our objective, USGS Peak. In order of difficulty, USGS Peak would take fourth place, but the other three already had been climbed.

USGS is not easily spotted from the surrounding valleys, an elusiveness only accentuated by the journey to get there. Indeed, the first impediment is the difficult drive, and if you make it to the end of the road, you still have to hike a long way over rough terrain. The route starts out on the deteriorating trail I mentioned, which passes through stretches of fir and pine separated by sagebrush-covered flats to reach a point where Long Lost Creek flows south through a steep canyon into the main valley. The creek tumbles down this canyon in fits and spurts, losing six hundred feet of elevation in less than a half-mile. Our route up this canyon was blocked at one point by a hundred-foot-high waterfall that dropped over a vertical wall. We had to detour around this obstacle by climbing two hundred feet up a dusty talus slope, only to then suffer the indignity of a seventy-five-foot loss in elevation to get back down to the stream above the waterfall. As we continued up, we passed three smaller waterfalls, which fortunately were easier to bypass.

After the fourth waterfall, we arrived at a spectacular hanging valley. Our route from this point traversed west under the toe of the north ridge to a small pond in the cirque that houses the north face. Head-on, the face looked extremely steep. Slender snow ramps climbed up itsshadows. We picked the easiest route across the broken surface of the cirque and reached the bottom of the face in another twenty minutes.

Ice axes in hand and crampons on our boots, we started climbing the first steep snow pitch. In the morning shadows, the snow was still rock-hard. Near the top of this pitch, we hit water ice, on which neither the points of our crampons nor the pick on our ice axes could make a dent. We used our ice axes to cut several small steps to cross this treacherous patch, and reached the face’s steepest section.

We then climbed a rock buttress for a short distance. Rather than remove our crampons, we let them clink and scrape on the rocks. The footing was good and we quickly reached the snow chute that we hoped would take us to the summit, still another thousand feet above us.

Five hundred feet up this chute, we cut a small platform in the snow. Each blow from the ice axe sent a cascade of ice down the slope. We sat down to rest. The cirque spread out below. The tops of the ridges that enclosed the eastern and western sides of the cirque were nearly level with us. The snow had varied in quality as we climbed, from polystyrene-like to water ice to unconsolidated “rotten” snow. While it was clear that anything that got loose on the slope would soon end up in the rocks five hundred feet below, our precariousness was accompanied by exhilaration.

Above our resting perch, we reached the crux of the climb, a rock band that constricted the snow chute into a narrow ribbon. We started to climb up the rock but it quickly steepened and we moved back onto the snow. Above the constriction, the slope moderated a bit and fifteen minutes later we were on the narrow summit ridge, which we followed to the top, conquerors of a north face. Rank: 2.

Diamond Peak, Lemhi Range

After an early-season snowstorm in November 1981, the weather had moderated somewhat, but the climbing season was once again coming to an end. Enticed by the distant view of Diamond Peak from our home in Idaho Falls, Dana and I set our hearts on climbing Idaho’s fourth-highest mountain. We left Idaho Falls early on a Saturday,determined to either make the summit or at least give it our best effort. From distant Idaho Falls, it was impossible to gauge the actual snow depth on the peak but the closer we got, the better conditions looked. From the base of the peak’s eastern ridge, the route appeared to be in perfect condition.

It’s fitting to end this mountain odyssey in the Lemhi Range, because it’s thestate’s quintessential fault block linear mountain chain. It runs from Salmon in a southeasterly direction for more than a hundred miles to the Snake River Plain, and varies in width from ten to fifteen miles. The Pahsimeroi and Little Lost River Valleys border the range on its western side, while the Lemhi and Birch Creek Valleys parallel its eastern side. The range was named in 1917 (Lemhi is a corruption of “Limhi” from the Book of Mormon) although signs of tribal habitation that date back eight thousand years can be found along the base of the range. The name those people gave to the range is lost in time.

It’s the home of Bell Mountain and many other impressive summits. Diamond Peak’s pyramid shape dominates the southern end of the range. At one point it was known as Dome Peak, but that name doesn’t suit its triangular shape. The first attempt to climb Diamond Peak was made by Vernon Bailey of the US Biological Survey in 1864 and the first known successful climb was in 1914 by a USGS survey party.

On the lower, broader section of the peak’s eastern ridge, we spooked a mountain lion, an experience that came and went in a flash. As we reached the transition between the broad, grassy ridge and the climb’s ridge, we startled a mountain goat that was probably the mountain lion’s intended prey. The Wild Kingdom portion of the climb was then over, and it was just us and the beautiful ridgeline. We used our ice axes to negotiate several small snow patches but mostly we climbed short, steep pitches or dark rock. All the while, the view below us expanded, until it looked as though we could see the curve of the earth on the southern horizon. What more can a climber ask of a mountain than a mesmerizing shape, a challenging route, and a stunning vista? Diamond Peak and its east ridge—undoubtedly the best ridge climb in Idaho—has it all. Rank: 5.

Next: Travels with John

ARTICLE INDEX