SUMMIT, January/February 1985, Volume 31, No. 1

Dana edged out farther along the ledge to its end and out of view into a slimy, debris-filled chimney. I waited alone, watching the bottom of the cirque below me. Then, through the wind, I just barely caught her words,“It won’t go.” I stopped my vigil and leaned back to wait for her return. A rock began to skitter down a slope somewhere close by. It sounded far off and then, before I could move, the roar of moving rock replaced the wind. Rocks crashed down and spilled out of the chimney with a sickening racket. I called out. Nothing. My first instinct would have been to panic, but climbing in the Seven Devils immunizes you to the fear of loose, rotten rock. Then when the last rock came to a rest and the dust began to settle, I heard Dana’s voice from up above. “Rock,” she called out.

Dana edged out farther along the ledge to its end and out of view into a slimy, debris-filled chimney. I waited alone, watching the bottom of the cirque below me. Then, through the wind, I just barely caught her words,“It won’t go.” I stopped my vigil and leaned back to wait for her return. A rock began to skitter down a slope somewhere close by. It sounded far off and then, before I could move, the roar of moving rock replaced the wind. Rocks crashed down and spilled out of the chimney with a sickening racket. I called out. Nothing. My first instinct would have been to panic, but climbing in the Seven Devils immunizes you to the fear of loose, rotten rock. Then when the last rock came to a rest and the dust began to settle, I heard Dana’s voice from up above. “Rock,” she called out.

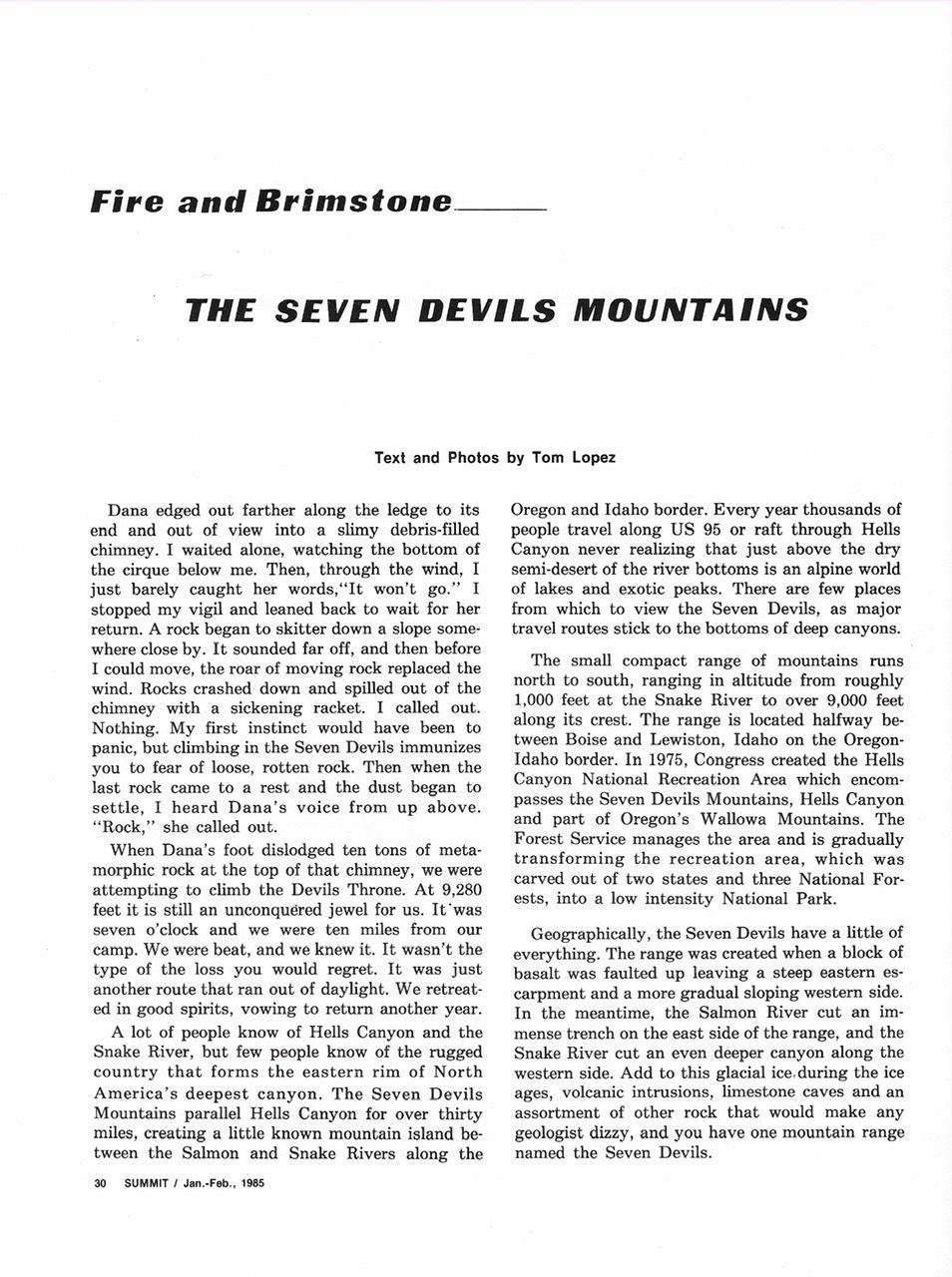

The Seven Devils from Windy Gap.

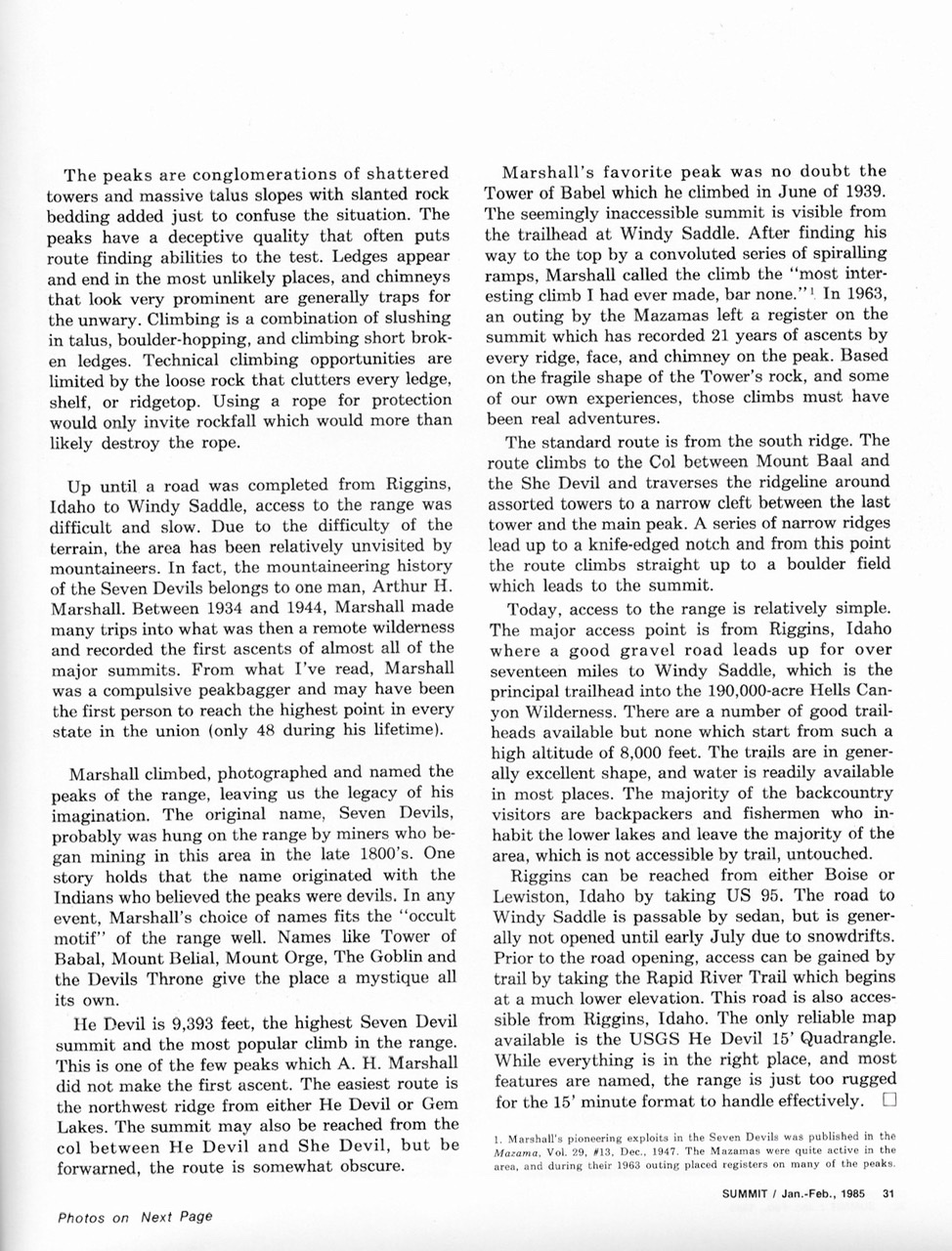

When Dana’s foot dislodged 10 tons of metamorphic rock at the top of that chimney, we were attempting to climb the Devils Throne. At 9,280 feet, it is still an unconquered jewel for us. It was 7:00PM and we were 10 miles from our camp. We were beat and we knew it. It wasn’t the type of the loss you would regret. It was just another route that ran out of daylight. We retreated in good spirits, vowing to return another year.

A lot of people know of Hells Canyon and the Snake River, but few people know of the rugged country that forms the East Rim of North America’s deepest canyon. The Seven Devils Mountains parallel Hells Canyon for over 30 miles, creating a little-known mountain island between the Salmon River and the Snake River along the Oregon/Idaho border. Every year, thousands of people travel along US-95 or raft through Hells Canyon, never realizing that just above the dry semi-desert of the river bottoms is an alpine world of lakes and exotic peaks. There are few places from which to view the Seven Devils since major travel routes stick to the bottom of deep canyons.

The Devils Throne as viewed from the summit of Mount Belial.

The Seven Devils is a small, compact range of mountains that runs north to south, ranging in altitude from roughly 1,000 feet at the Snake River to over 9,000 feet along its crest. The range is located halfway between Boise and Lewiston, Idaho on the Oregon/Idaho border. In 1975, Congress created the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area which encompasses the Seven Devils Mountains, Hells Canyon and part of Oregon’s Wallowa Mountains. The Forest Service manages the area and is gradually transforming the recreation area (which was carved out of 2 states and 3 National Forests) into a low-intensity National Park.

Geographically, the Seven Devils have a little of everything. The range was created when a block of basalt was faulted up, leaving a steep eastern escarpment and a more gradual-sloping West Side. In the meantime, the Salmon River cut an immense trench on the East Side of the range and the Snake River cut an even deeper canyon along the West Side. Add to this glacial ice during the ice ages, volcanic intrusions, limestone caves and an assortment of other rock that would make any geologist dizzy, and you have a mountain range called the Seven Devils.

The peaks are a conglomeration of shattered towers and massive talus slopes with slanted rock bedding to confuse the situation. The peaks have a deceptive quality that often puts route-finding abilities to the test. Ledges appear and end in the most unlikely places. Chimneys that look prominent are often traps for the unwary. Climbing is a combination of slogging through talus, boulder hopping and climbing short broken ledges. Technical climbing opportunities are limited by the loose rock that clutters every ledge, shelf or ridge top. Using a rope for protection only invites rockfall that would more than likely destroy the rope.

Until a road was completed from Riggins, Idaho to Windy Saddle, access to the range was difficult and slow. Due to the difficulty of the terrain, the area is seldom visited by mountaineers. In fact, the mountaineering history of the Seven Devils belongs to one man–Arthur H. Marshall. Between 1934 and 1944, Marshall made many trips into what was then a remote wilderness and recorded the first ascents of almost all of the major summits. From what I’ve read, Marshall was a compulsive peakbagger and may have been the first person to reach the highest point in every state in the union (only 48 states during his lifetime).

Marshall climbed, photographed and named the peaks of the range, leaving us the legacy of his imagination. The original name, Seven Devils, probably was hung on the range by miners who began mining in this area in the late 1800s. One story holds that the name originated with the Indians who believed the peaks were devils. In any event, Marshall’s choice of names fits the occult motif of the range well. Names like Tower of Babal, Mount Belial, The Ogre, The Goblin and Devils Throne give the place a mystique all its own.

He Devil (9,393 feet) is the highest Seven Devil summit and is the most popular climb in the range. This is one of the few peaks of which A. H. Marshall did not make the first ascent. The easiest route is the Northwest Ridge from either Echo Lake or Gem Lake. The summit can also be reached from the col between He Devil and She Devil, but be forewarned that this route is somewhat obscure.

Marshall’s favorite was no doubt the Tower of Babel which he climbed in June 1939. The seemingly-inaccessible summit is visible from the trailhead at Windy Saddle. After finding his way to the top by a convoluted series of spiraling ramps, Marshall called the climb the “Most interesting climb I have ever made, bar none.” In 1963, an outing by the Mazamas left a register on the summit which has recorded 21 years of ascents by every ridge, face and chimney on the peak. Based on the fragile shape of the Tower’s rock and some our own experiences, those climbs must have been real adventures.

The standard ascent route is via the South Ridge. The route climbs to the col between Mount Baal and She Devil and traverses the ridgeline around assorted towers to a narrow cleft between the last tower and the main peak. A series of narrow ridges lead up to a knife-edged notch. From this point, the route climbs straight up to a boulder field which leads to the summit.

Today, access to the range is relatively simple. The major access point is from Riggins, Idaho where a good gravel road leads up for over 17 miles to Windy Saddle, the key trailhead in the 190,000-acre Hells Canyon Wilderness. There are a number of good trailheads available but none which start from such a high altitude (8,000 feet). The trails are in generally excellent shape and water is readily available in most places. The majority of the backcountry visitors are backpackers and fishermen who inhabit the lower lakes and leave the majority of the area (which is not accessible by trail) untouched.

Riggins can be reached from either Boise or Lewiston, Idaho by taking US-95. The road to Windy Saddle is passable by sedans but is generally not open until early July due to snowdrifts. Prior to the road opening, access can be gained by trail by taking the Rapid River Trail which begins at a much lower elevation. This road is also accessible from Riggins, Idaho. The only reliable map available is the USGS He Devil 15-minute quadrangle. While everything is in the right place,and most features are named, the range is just too rugged for the 15-minute map format to handle effectively.

Marshall‘s pioneering exploits in the Seven Devils were published in the Mazama, Vol. #13, December 1947.

Next: UI Denali Expedition