Editor’s Note: see additional photos assembled by Jacques Bordeleau at the following link: Gordon K. Williams Photos

My friend, high school classmate, climbing and adventure buddy Gordon Williams (aka Stein Sitzmark and, on occasion, “Imstein”) passed away on Tuesday July 23rd at age 69 and 3/4. He leaves a lot of good friends and his loving family behind.

Gordon was trained to be a registered surveyor but was also an artist by choice and inclination. Many folks enjoyed his keen wit and loquacious manner. He was interested in many, many things, but his photography has been a major achievement since the late 1960s.

I met Gordon soon after his family moved to Ketchum in the mid-1960s. Although I was a year ahead of him in high school, we were almost the same age. Like many have since, I found him interesting and likable, but we were not close friends in high school. However, I must confess to being the person who introduced him to roped rock climbing.

The Early Days

In the Summer of 1969, Jim Cockey took an afternoon to teach his younger half-brother Art Troutner and me some key elements of roped rock climbing near McCall. We learned how to belay climbers with a rope, hammer in pitons to anchor belays and rappel off a rock cliff, in a few short hours of instruction. I went home to Ketchum and ordered a climbing rope, some soft-iron pitons and aluminum carabiners from REI. I then proceeded to share my inadequate and dangerous knowledge of the rudiments of roped technical climbing with Gordon and his high school classmate, Chris Hecht. They were instant converts and soon Chris thereafter ordered better climbing gear. That Winter, we read up on climbing techniques and practiced climbing knots until we could tie them while stoned.

By the Summer of 1970, we were ready for real mountains. Gordon, Chris and I started with a bang by climbing 10,981-foot Boulder Peak near Ketchum in early June. Next, we convinced a number of friends to hike into Wildhorse Canyon in the Pioneers for the 4th of July weekend. But during that weekend, Chris, Gordon and I encountered steep and difficult rock on the North Face of 11,771-foot Old Hyndman Peak and an oncoming thunderstorm convinced us to retreat.

The Decker Flat Climbing & Frisbee Club

For our next trip into the Pioneers, we were mentored by my “somewhat” experienced climber-friend Harry Bowron, who summered in Stanley. Harry had been exposed to roped climbing on various Sierra Club trips and had recently survived a long National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) outdoor skills course in the Wind River Range. His knowledge and abilities helped our climbing skills considerably.

It was a hot day in late July 1970, during our hike into Mount Regan above Sawtooth Lake. Pursued by evil, we hurried up the dusty trail. Our packs were heavy, each with 60-70 pounds of climbing and camping gear. It was a hot, humid and windless morning. We were sweating hard and were being chased mercilessly by a full-strength squadron of horseflies.

Flies dive-bombed us incessantly, trying to break through the curtain of insect repellent we had drenched ourselves with. They grew in numbers until it was difficult to see the sun through the voracious fly swarm above our heads. Frenzied buzzing horseflies became noisily trapped in our long hair and select kamikaze flies would creep between our sweaty fingers to inflict amazingly painful bites.

It was starting to look like we might become the first known case of climbers eaten by flies when suddenly all the horseflies dipped their wings, did a double roll and turned tail. They flew off down-canyon–a roaring cloud of instant misery. The reason for their retreat stood by the trail: snarling evilly, shovel in hand. Even horseflies don’t mess with SMOKEY THE BEAR!! Of course, a sudden breeze might have helped too.

We had arrived at the Wilderness Boundary!! There beside the plywood Smokey was an 8-foot tall, solid redwood sign proclaiming:

ENTERING SAWTOOTH WILDERNESS AREA

CHALLIS NATIONAL FOREST

PLEASE REGISTER FOR YOUR OWN

PROTECTION!

We had some fun filling out the overly-detailed registration form, but then none of us wanted to put our name on it as group leader. In a moment of inspiration, I exclaimed “Let’s call ourselves the Decker Flat Climbing & Frisbee Club” and, since I thought of it, I get to be manager.

We had elections on the spot and Gordon chose to be Social Chairman, Harry Bowron, Treasurer and Joe Fox, Member at Large. The next day we climbed Mount Regan (which was somewhat challenging) and had a great time. Our mountain fun was just starting. We never had scheduled meetings or dues but, in order to become a member, you had to go climbing with another member. Of course, Gordon took his duties as Social Chairman seriously. He was soon adding females to our club. I must admit to being jealous of Gordon’s social skills in the 1970s and 1980s. His girlfriends were always attractive, assertive and intelligent. Gordon was a “babe-magnet” of the first magnitude. Thus he was the perfect Social Chairman.

In the early 1970s, Idaho mountaineering was a different world than now. It was a world without good USGS maps, climbing guidebooks, cell phones, GPS devices, an internet to access for climbing information and satellite rescue beacons. Thus, we suffered considerable obstacles to safe and sane mountaineering but, let me assure you, rock climbing and mountaineering in Idaho was a helluva lot more adventurous and a lot more fun then than it is now. Amazingly, although some of our climbing students suffered long scary slides on steep snow slopes, there are no serious climbing injuries or deaths in the history of the Decker Flat Climbing & Frisbee Club.

Gordon glissading “way too fast” on our way down from climbing the highest peak in the Sawtooths (June 1971).

Gordon As A Climbing Pioneer

In the early 1970s, Gordon was active in attempting the first Winter ascents of some Sawtooth Range peaks which even difficult to climb in Summer. There were some setbacks, but he was integral in the first Winter ascent of the difficult pinnacle, The Finger of Fate, and a large peak with no easy way to the summit, Mount Heyburn.

In mid-March 1971, Gordon, his Seattle friend Roxanna Trott and I enjoyed a somewhat unconventional moonlight Winter ascent of Boulder Peak. We knew the snow was very firm with near zero avalanche danger (despite our lack of avalanche awareness training). Gordon and I departed Whiskey Jacques at 1:00AM with a drink, picked up Roxanna at her place, drove to Boulder Flat and skied into the Southwest Side of Boulder Peak on Styrofoam-hard snow under a full moon. We arrived on the summit at dawn and were back in Ketchum for a late lunch.

Here’s my photo of Gordon & a friend Roxanna Trot, on a winter moonlight ascent of 10,891’ Boulder Peak near Sun Valley.

Pioneer Cabin

In 1972-1973, Gordon, Chris Puchner, Robert Ketchum and others worked on the now locally-famous restoration of Pioneer Cabin above Sun Valley. Pioneer Cabin (a 1937 Sun Valley Company high mountain ski hut) sits on a scenic ridge at the edge of the Pioneer Mountains. Here’s a link to an Idaho Public TV article on the cabin which mentions the history: Outdoor Idaho. Gordon’s hard work on Pioneer Cabin and his insistence on painting the DFC&FC slogan “The Higher You Get, The Higher You Get” on the newly-repaired roof of Pioneer Cabin made both him and our club famous in western mountain lore. The story has appeared in several outdoor magazines.

Gordon and the Finger of Fate

Gordon was active at rock-climbing and mountaineering through the 1970s. Gordon really enjoyed climbing the challenging Open Book Route on the Finger of Fate in the Sawtooths. By 1978, it was a routine climb for him and Mark Sheehan. On one of these outings in 1978, they were hit by a severe thunderstorm just below the top of the Finger. Suddenly lightning was hitting nearby peaks and it was raining hard. They could not climb the final difficult summit pitch in the rain and with their single rope, descending the Open Book Route was unthinkable. Getting off the rock was essential and they started to down climb on what seemed to be a safer alternative. As Gordon rappelled, the rope slipped . . . but I will let Gordon tell the story.

Gordon’s Close Call by Gordon K. Williams

In late July 1978, I hiked into Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountains with my friends Mark and Gail Sheehan. We were off to do our favorite rock climb, the Open Book Route on The Finger of Fate. By 1978, I had climbed the classic Class 5.8 route a number of times and it had become normal for us to hike in, climb the route and return back to Ketchum on the same day.

Perhaps we made a bad choice. The weather was deteriorating and we put on the climb anyway. That is how we first met Brent Bernard. When Brent and several of his friends had arrived at the base of the Open Book, we hadn’t yet finished the first pitch. They sat down to wait for us. While waiting, they looked at the sky. The sky told them to back off. They walked away. That was a good choice.

Twenty feet of steep snow guards the bottom of the climb. In early July, it is cold on the North Side. First thing in the morning, that snow is hard. We chopped steps, kicked the snow off and gingerly stepped onto the rock. You must immediately swarm up a blank section with wet boots. This may be the crux. There is no warm up. There is not much to work with. Go up or go home.

From the belay ledge, I watched Mark Sheehan levitate up the first pitch. It is the only place big enough for two and a welcome refuge after working around the foreboding overhang. Looming at the top of a perpetually cold jam crack, the clean overhang extinguishes hope. There appears to be no way around it. One must push up under that overhang then exchange heel for toe in the crack. Turning around to face out puts your head where the next move becomes visible. Exit right onto the face for a “Thank God” handhold that is nearly beyond your reach. Swinging across on one hand brings you to where it is possible to work up the face and mantel on the ledge. Some consider this the crux problem. On arrival, Mark expressed pleasure. We were having fun.

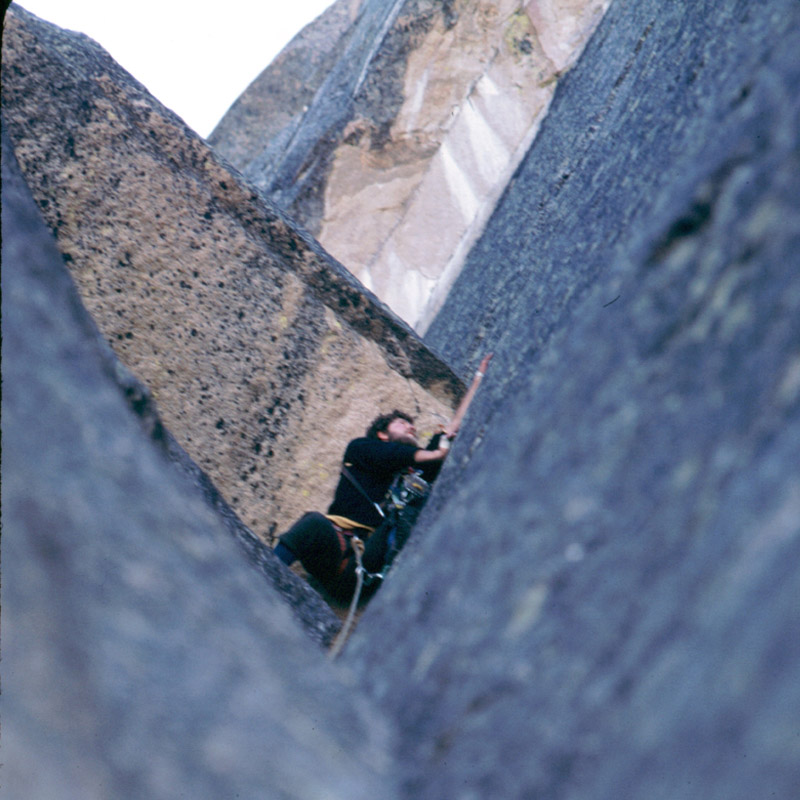

Gordon at the top of the jam-crack lead on the second pitch of the Open Book. The crack ends under the overhang and climbers are forced out right onto thin holds. Mark Sheehan Photo

Our plan had been to travel light and fast. One rope, three slings and about a dozen chocks would be enough. We had everything necessary and nothing more. Heavier clouds were beginning to build. They told us to pick up the pace. Two more pitches would bring us to the top of the Book. Then send a short pitch up the ski tracks, crawl under the summit block, jump the gap and bag the summit. We would rappel from an old bolt and down climb to another short rap above the saddle. Our plans began to change half way through the third pitch.

Lichens cover most of the rock on the Finger. Lichens are composite organisms consisting of a symbiotic relationship between an alga and a fungus. The fungus surrounds the algal cells, enclosing them with complex fungal tissues unique to lichen. Lichens are capable of surviving extremely low levels of water content. When fully hydrated, the complex fungal tissues become slippery. Rehydration requires several minutes. We were still adapting to light rain and slippery rock when thunder started echoing off nearby mountains.

Suddenly our location near the top of a prominent pinnacle seemed imprudent. We were climbing a lightning rod. Mark and I are both afraid of lightening. We wanted to get down fast. From the ridge above the Book we had two choices. Knowing the South Side to be much shorter, we decided to rappel that way. Mark split the coil while I threw a sling over a horn on the ridge. No time to tie knots at the ends – throw the rope. More thunder and louder now we were in a panic to get off. Assemble four carabiners as a brake, clip into the line and ease gingerly to the edge. Wind was whipping rain from every direction. I would be careful not to slip on the wet rock or rap off the end of the rope.

Starting down with feet spread wide I was leaning back perpendicular to the wall so my boots wouldn’t slip. Descending slowly and looking down for more foot placements, I felt the line above release. Turning my head to look up, I saw the rope and anchor sling whipping against the sky above. My rappel anchor had slipped off the rock horn and I was accelerating in free-fall with hundreds of feet to the floor… a dead man falling.

Instantly I understood this to be the end. There was no hope of surviving such a fall. Anxiety and fear disappeared. Perhaps I stopped thinking. Time did not compress or elongate. There was certainly no flipping through old photos or videos of past events… no life flashing by. This was the end of the film, the part where the screen goes blank.

I have no recollection of hitting the wall. It knocked the wind out of me. I came to my senses gasping for air, unable to get the first bite. It was a raw shock, being jerked from some quiet place back into my body. Everything was confusing. I was hanging upside down pressing lightly against the rock wall. Nothing made sense. How could Mark have caught me? My hands found the rope and I struggled to get back upright. Stepping onto a toehold produced sharp flashes of pain in my left ankle. It was broken.

Mark was peering down from the ridge. Raindrops were hitting my face. The situation was coming into focus. He hadn’t caught the rope. Instead, it had snagged on the rock face. My rappel brake was jammed. This had prevented my sliding off the end of the rope after slamming into the wall. I used one hand to loosen the brake while holding onto the wall. Easing weight onto the rope again, I rappelled to a ledge fifteen feet below. Off rappel, a flick on the rope set it free from the snag… first try.

Mark was stranded on the ridge and the threat of lightening was not yet past. He had to get down. We were too far apart to throw the rope back up so Mark rummaged into his pack for cord. He lowered it… too short. Next he pulls out his boot laces and tied them onto the cord. Altogether it reached and I sent the rope up. Mark set a new anchor and rappelled to my level. We followed the ledge system around the East Side back onto the North Face trying to find the top of the PT Boat Chock Stone. We had enough gear to set two more rappel anchors and it would take five to get off the pinnacle. Several years earlier, we had left slings retreating down the Chock Stone route. In spite of their age, we hoped they might still hold our weight. They did.

Gail Sheehan was waiting at the bottom, wet and worried by our extended absence. We were greatly relieved to be off the rock. Climbing with a broken ankle was difficult, but hiking was out of the question. We had several miles of rough terrain to negotiate before getting to the lower end of Hell Roaring Lake. From there, another two miles of easy trail ran back to the car. Again Mark rummaged into his pack pulling out a Swiss army knife with a saw. He cut free some planks about an inch thick from the shell of a rotting hollow log. He then fashioned a splint that allowed me to walk by transferring some of my weight past the ankle and onto my left hand. It worked pretty well. Gail had taken all of the weight out of my pack and we three set off down the mountain. It was torture. By the time we reached the lake, I was exhausted and ready to confess. Mark offered to carry me. I said yes.

We rearranged the rope into a long mountaineer’s coil, split the coil into halves from the knot and draped it over Mark’s shoulders with the knot behind his neck. My legs ran through the coils transferring my weight onto his shoulders in a piggyback carry. Mark didn’t have to hold my weight with his arms. Gail carried our three packs. We set off down the trail. It was torture. After a few hours, Mark was exhausted and ready to confess. Gail was pretty much used up too. It was raining and the three of us were sitting on a log in the dark. We were too tired to start again. It was a low point. That is when Brent arrived.

They had waited at the cars. They knew something was wrong and were just about ready to drive out to call for help. Brent decided to walk up the trail a short way and see if he might find us. That is what he did… barefoot in the dark. We put my shoes on Brent and he carried me the rest of the way out to the road. Our self rescue had come to an end.

Life After Climbing

Around the time of the accident, he and Mark Sheehan bought an old hotel/boarding house at the onetime mining town of Triumph a few miles southeast of Sun Valley. In the early 1980s, they remodeled it into two separate two-story homes, with lots of room for possessions and the range of woodworking machinery he had acquired. Gordon’s half of that project provided him the comfortable home he had lived in since then.

Gordon knew he was lucky to have survived the accident and as a result he climbed less after that near disaster. I think flashbacks of his near death fall continued to bother him. By the 1990s he was hardly climbing at all, but Kim Jacobs talked him into climbing the Open Book on the Finger again in 2003, although she led all the pitches.

Somewhere along the way, Gordon and I adopted a toast that amused us both. We had both suffered close calls in our climbing and whitewater rafting careers and we both knew we were somewhat lucky to still be alive and healthy. Thus was born our, “Here’s to cheating death” toast at the end of every day of outdoor adventure. As some of us may have noted, “Life is so uncertain” and Gordon and I, and our friends appreciated that we had lived, for the most part, lucky and blessed lives.

In the late 1990s, Gordon started going to Nepal with small groups that were guided by his old friend Pete Patterson and Kim Jacobs. Gordon fell in love with Nepal, its people, and especially its mountains. He made 7 trips to Nepal between 1998-2008. I was lucky enough to accompany him and a small group of friends on two 16-day treks through some of the most spectacular mountains in the world.

Gordon was not doing what we considered mountain climbing but, in 2005, we did steep hiking up to a 17,500-foot summit for a spectacular view of nearby Mount Everest.

In 2010, my wife Dorita and I started doing regular multi-day climbing trips to the spectacular City of Rocks. Gordon was invited and soon joined in enthusiastically, but didn’t climb much. With the urging of our “old” friend, noted climber Jim Donini, we started sponsoring yearly camp-outs for mostly older climbers. Although Gordon seldom climbed at these meetings, he enjoyed being around other climbers and the scenic crags of the area.

At our gatherings, climbers from all over the U.S. enjoyed Gordon, his good temper, his stories, his wit, and his wisdom, as did we all. This year, including 4 nights at the City of Rock outing, my wife Dorita and I got to enjoy Gordon’s fine company on some, or all, of 10 precious days.

Gordon also became involved in white-water rafting in the 1980s and survived many challenging river trips, including two Grand Canyon adventures. In 2016, we finally enjoyed a multi-day river trip with him, thanks to our mutual friend Chris Puchner. We loaned Gordon our “sportscar” raft and he navigated it down the large and sometimes scary rapids of Idaho’s Main Salmon River without mishap.

Part of the fun of being around Gordon was his rich imagination. His little plastic friend Piglet traveled many places with him and proved fascinating to Gordon’s many female friends.

Here’s Gordon at the City of Rocks sharing a drink with Piglet while my wife Dorita politely averts her gaze.

Although Gordon continued to work part-time, he was usually willing to go explore old mines or Native American rock art with us.

This photo of Gordon was taken this Spring as we were hiking back from a 1880s mine we explored west of Hailey.

Final Thoughts

I deeply appreciate that except for a miraculous catch of Gordon’s falling rappel rope by a rock flake, during a thunderstorm on the Finger of Fate back in 1978, we almost certainly would have lost Gordon 41 years ago. So we have been in the bonus Gordon round for many, many years, which I know we are all grateful for.

So we have been blessed that Gordon survived not only that 1978 storm and rappel failure, but he also graced us with his lively presence until now.

I miss him.