[Editor’s note: Lyman Dye has provided a memoir for our reading enjoyment, Heeding The Call of the Mountains. Lyman is one of the giants of Idaho climbing and his many first ascents are documented in the book. He operated the first climbing guide service in the Sawtooths and also guided climbers, including the Iowa Mountaineers and the Mazamas, on many first ascents. This memoir begins in 1958 and provides a unique view into early Idaho climbing as well as Lyman’s Lost River Range adventures and Teton climbs.]

In the Fall of 1958, my wife Carol and I moved with our children to Arco, Idaho. I had taken employment with Arco Auto, the Ford dealership in Arco at the time. I was to assume the duties of the auto-body and paint department. We did not have a place to live at the time, so we took residence in the Lazy A Motel. We had rooms in the north section of the Motel behind the normal nightly stay section that you see when driving along the street.

We had not been there many days when one evening, a knock came on our door–the local Ward Bishop and Counselor made us a visit. I don’t remember having attended a meeting in Arco before they made this visit. They visited with us for a few minutes and informed us that the LDS Church was just beginning a new program for boys 14-18 and wanted to call me to be the advisor for the group. They were having an introductory meeting for this program the next night and wanted me to attend. I had been an advisor for this age group previously in Afton, Wyoming when we were living there, so it was something I was interested in. The new program was to be run more like a club with officers and an advisor to help the young men run their own program. My responsibility would be to guide the avenues they wished to explore and participate in.

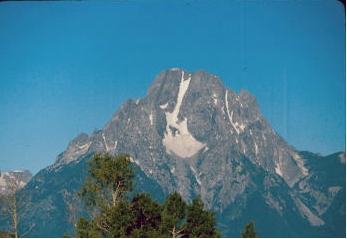

Mount Borah. Lyman Dye Photo

During the course of the Winter as we had our meetings and planning sessions, I suggested the possibility of climbing Idaho’s tallest peak, Mount Borah, which was located between Moore and Challis, Idaho. I had worked for 3 summers in the Salmon National Forest at Salmon and had considered climbing it as I drove back and forth from Idaho Falls to Salmon. I had made a stop on several occasions to contemplate the route I would need to take to the summit. The boys bought the suggestion and so we began to determine when and what we would need to be successful. I had done a lot of reading during my youth about climbing, so now I began reading in earnest for additional information.

Lyman Dye Photo

Fred Boyer, a local insurance salesman, church leader and father of one of the boys consented to be part of the hike. Fred really wanted to go with his son Wayne. I found out later that this was a concern for his wife Helen. She mentioned to my wife that Fred hardly walked to the bathroom or to his office, let alone something like climbing Mount Borah.

We were not smart enough to restrict the footwear of the participants. Fred wore engineer field boots and two of the boys wore tennis shoes as they were called in those days. We knew that other people had made the hike and attire and footwear was not a major concern in our minds. It had not become a part of my thinking to plan for the dangerous possibilities when attempting a climb at this point. I was to learn that conditions are not always favorable and can change very quickly at higher elevations.

Lyman Dye Photo

There was no climbing brochure available from the Forest Service as to route or conditions to expect while on the mountain. I was not too concerned because it was not something that needed expedition-type planning. Well, we all learned a few things with the experience as we endured the trek into the mountain wilderness. I remember the question that was repeated over and over to me: how much farther. We were smart enough to get an early start and so we made the summit in plenty of time to escape any danger of afternoon thunderstorm activity that might develop. We ate our lunch on the top and basked in the warmth of the sun.

Lyman Dye Photo

It was on the way down that we began to get complaints from the boys of things going on with their feet that was uncomfortable. The two boys with gym shoes were developing blisters as was Fred. The constant movement of feet within loose shoes is something to be avoided. We ended up administering to the two boys to ease their pain and concerns before we returned to the transportation. I had always made it a practice to carry consecrated oil with me wherever I went, a pattern my father had taught me.

When it became evident that we might not get back before dark, I instructed Fred’s son how to get to the car and start a fire and honk the horn to give us a sound to move to if it got too dark. We all made it down safely loaded ourselves up with water and a little sugar to make us feel better then started for home. Helen Boyer and some of the other mother’s had called my wife being concerned about the lateness of the hour and no boys. She has learned to calm others as my trips into the wilderness don’t always go exactly as planned. Needless to say, all were happy when we arrived home safe and joyous about our accomplishment.

Lyman Dye Photo

I decided that we needed to learn some more technique if we were going to do more of this. I took James Reid the post president with me to the Tetons to attend a 3-day course on mountain climbing. Jake Breitenbach was our instructor. Jake was killed later on the American Expedition to Everest. We learned a lot of how to protect each other while climbing, how to read the terrain, and not waste energy in the mountains.

On our way home from that training as we were coming down the Idaho side of Jackson Pass, we got to watch the rescue of some people who had gone off the road and rolled their car down into the gully. Our watching that drove home to us some of the simple dangers that are around us each day. James Reid soon had to move away and the interest in the group kind of died off in relation to mountain climbing.

Wayne Boyer was still interested in doing more climbing so he talked to his uncle Art Barnes (who was some years older) into going with us on future climbs. We soon became known as the EE-DA-HOW mountaineers. When I became serious about starting a guide service, it seemed natural to use EE-DA-HOW Mountaineering as the name of the school. Art composed a song we had great fun singing and yodeling our way on many a trip. We on occasion would get alumni of Butte County High School to pay us to paint their graduation year number that had faded on the hill east of town in order to get money to finance some of our trips. What fun we had learning and enjoying the mountains together.

I continued to read from “Freedom of the Hills,” “Handbook of American Mountaineering,” American Alpine Journals and other books I could get my hands on to bolster my knowledge on technique, experiences and joys of the mountains. Summer was a time I always looked forward to. It was the end of Winter and the start of climbing season!!

Sacajawea and McKinley

June 1969, James Reed and I had scheduled to make a climb of Mount McKinley, a peak south of Mount Borah one time. James came over the night before we were to go and told me he had a spat with his girlfriend. I told him to go take care of whatever their differences were. I said I did not want him along with his mind on other things. Climbing was dangerous enough without having your mind on other things at the same time. Distraction is not good. I was pretty broken up about not being able to go, having my heart set on that trip. Carol and I had a long talk and, with her consent, I was allowed to go alone–the rule being that I explained the route I was to take and would not deviate from it. I also would not engage myself in climbing difficulty that was in the upper realm of my capability.

Lyman Dye Photo

I went up to the Borah access place and spent the night. The next morning I started up the Southwest Ridge of Borah to the false summit. I then crossed over on the ridge to Sacajawea. Summitted then turned south along the ridge to McKinley. I summitted McKinley and decided that I would return to base rather than try to cross over the deep saddle called Leatherman Pass and do Leatherman Peak. This would shorten my trip and I would not camp out that night. I had brought in my pack, a one pound sleeping bag and other things I might need in case of injury or other unplanned hazards because I was climbing alone. At this point, I would much rather of not had the added weight and would have been happy to have it back in the car. I came down the canyon under Slate Peak and I was really tired fighting all the thick willows and rocks on either side of the creek.

I found a beautiful spot in a small meadow along the side of the creek and had a short nap and enjoyed listening to the birds and creek trickle. I ended up carrying the pack in my arms out on the flat, because it was easier to drop than swing it off my shoulders when I got tired. I was really beat when I got to the car. Mount Borah became the warm up climb for us each year. A couple of times we did King Mountain because of the snow conditions.

Mount McCaleb

Mount McCaleb with it cliffs and bald knob of a summit posed a desirable peak for us to do. We didn’t know how to get over to it because of the city and farm land. We took a road that someone had explained to us was the route to the old city power plant over near the base of the peak. We found ourselves on a farmer’s service road and a gully between us and the road we decided we needed to be on. I chose to drive down the bank of the gully to the road rather than try to figure how to get over there. We got down to the other road and this farmer came driving up wondering what we are doing. I explained that we were wanting to climb McCaleb, and he said “Heavens, I rode my horse up there; nothing to it.” He laughed and told us where to go and left chuckling to himself. We found the old power plant and had our supper and kidded ourselves about what the farmer had said.

Mount McCaleb as viewed from near Mackay, Idaho.

We went up the slope as direct as we could considering the miserable loose rock of which it was composed. We seemed to be learning the hard way, what should have been obvious, had we considered rock formations. It seemed that we took one step forward and two steps backwards. We joked that what we should do is turn around and take one down and slide two up, it would be faster. We reached the cliffs and we were not happy with what we found. The rock was fairly smooth with few cracks of any depth.

We scouted out several cracks and we slowly moved around the base of the cliffs to the east. We found nothing that we wanted to attempt climbing until we hit the East Side and found a workable couloir which we climbed to the summit. There was nothing on that side of the mountain that a horse could be ridden up. However, on the West Side, the slope was a lot more gentle and it might have been possible the farmer could have gotten his horse up there, but it would not have been enjoyable. We took a fairly direct route down the slope to the car and found some flowers and other growth that pleased our eyes. The descent was a little like skating on a field of ball-bearings.

Leatherman Peak

In September 1963, the first time we climbed Leatherman, we thought we would use mechanical mules. These were the forerunners of all-terrain vehicles, built in home workshops. They had two small diameter balloon-tired wheels, the rear one chain driven by a motor set between the two wheels. A padded seat mounted to the framework of the mule with a flat spot behind allowed it to haul game or whatever else one desired to carry. We considered parking the pickup at Jones Creek and riding the mules along the old water line terrace to Cedar Creek and then traverse the ridge back to a Jones Creek, drive the pickup to where we had left the mules, pickup them up and be on our way.

Leatherman Peak as viewed from Sawmill Pass.

The ride over to Cedar Creek was horrible, it about beat us to death riding the mules with packs on our backs. The embankment for the ditch was not very wide in places and was a real hassle. We got over to Cedar Creek alright and went up the creek past the old cabin and did the West Face above Leatherman Pass. In earlier times, they would drive horses over this pass to and from the Pahsimeroi Valley.

We did this climb on Labor Day and the wind was blowing hard with gusts in the 40MPH range. We tried to keep the wind at our backs so it blew us into the wall as we climbed. The climb up and descent through the timber below the open pass was beautiful. The setting of the cabin next to a pinnacle along the creek was fantastic. What a place to have a cabin–lonely but beautiful. Leatherman Peak was typical limestone–not all that solid but not that dangerous you held your breath with every move either. When we got back down to the mules, we rode them out to the highway and then followed the edge of the highway over to Jones Creek and the truck. We never used the mules again. We had our fill of those body-beaters. We did make climbs on Leatherman Peak again in 1969 and 1973 following different routes than we had ascended the first time.

Mount Breitenbach

We had discussed naming a peak in Idaho after Jake Breitenbach, the guide from the Exum School of Mountaineering who had really lit the fire in me to climb. He had been killed on Everest when a 200-foot ice tower had collapsed and buried him in the Khumbu Ice Fall. I wrote a letter to the Governor of Idaho asking his permission to do so and he replied if he had the power to do so consider it done. I wrote the Geological Society and included the letter from the Governor and told them our thinking and they sent a letter back after a few weeks granting the permission and formally naming the peak Mount Breitenbach, for Jake.

Mount Breitenbach. Lyman Dye Photo

In September 1963, we went up Pete Creek, parked the truck, worked our way up into the basin and attacked the face between Breitenbach and the lesser peak to the south. The climb was typical limestone scree and talus with some fair blocks encountered on the upper face. Once on the ridge, we followed it to the summit, ate our lunch and left a copper cylinder on the summit to mark our ascent. We also ran the ridge over to the southern peak and left a cylinder there as well. We had now climbed virtually of all the peaks from Mount Borah along the ridge to Mount McCaleb.

I think of all the mountains we climbed along the Lost River Range, the most pleasant and rewarding were Mount Borah, Sacajawea, McKinley and Leatherman. I think on a good day, those 4 peaks could be done in one day but it wouldn’t leave much time to enjoy yourself along the way. I think that it should be done from the north starting with Mount Borah and finishing with Leatherman Peak having camped on the East Side up the West Fork of the Pashimeroi River.

Moonrise or Sunrise?

I took the explorers from Arco one time into Copper Basin on an outing. We found us a good place for a campsite, had supper and collected some wood for the next morning. We had planned on doing a little fishing and scrambling around on the hills in the area. We sat around talking until we got sleepy, even watched a satellite pass over us. We told some stories and finished talking about some eternal things. We all snuggled down and went to sleep and then I became aware there was a fire going and conversation going on.

I got up and asked “What was going on?” They said, “It was time to get up; the sun was starting to rise.” I started to laugh and they didn’t think it was funny. I said, “Well, if you guys will watch closely that is not the sun coming up; it is the moon.” They learned what it was like to experience what we call a moon rise. Ha-ha. It ended up being a beautiful full moon and was pretty light out, but certainly not the sun. Well, we went back to bed having used most of our wood supply, but it was a fun lesson and experience. I think they all learned the difference between a sunrise and moonrise.

Discipline

We planned a Church Explorer trip to Redfish Lake once and I got delayed at work the day we were scheduled to leave. Two of the boys went over early in the afternoon. The other leader took the remainder of the boys over and I was to meet them later when I got off work. When I got there, the other leader informed me that the two boys who had gone over earlier had taken beer with them and had been drinking. I called all the boys together and we discussed what had gone on. We allowed the boys to go to bed and get a good night’s rest while we decided what we were to do.

The next morning after breakfast was over, I told the boys to pack up. We were going home. True, not everyone had participated, but we were a group and we shouldered a responsibility together. I contacted the Bishop on our return and told him what had gone on. He told me to handle it in whatever way I thought was right. All the parents were notified why we had come home early and what our concerns were. That was the only time I was ever faced with that kind of circumstance again.

We went over and spent a week the next year and had a wonderful time. We had our camp at the upper end of the lake at the inlet. One of the ward members hauled us in and out. A neighbor from Arco was over at the lake and came over with his boat one day with a bunch of treats and groceries for us. He wanted to help in this way for us to have an enjoyable trip. One afternoon, we laid out on the floating dock and got good and sunburned. Another friend of mine came up with his boat and took all the boys for a spin on water skis. There were a couple of times during the outing I had to keep my eyes glued to a couple of the boys who had struck up with a couple of girls, but things worked out well.

We dug a hole in the beach sand built a fire left the coals in the pit, put our meal in the dutch ovens, placed them in the pit and let them cook while we played throughout the afternoon. We invited some of our friends over for the evening and we had a wonderful meal and visit.

Preparation

I used to keep my pack filled with essentials so that I could be ready to go almost on a moment’s notice. One day I got a call at the site telling me that one of our Boy Scouts had come up missing at the Treasure Mountain Camp. I told the Bishop to go over to my place get my pack from the garage and pick me up at the site and I would be ready to help search for our Boy Scout. We arrived at Driggs and were notified that the boy had been found. He had left his coat where they had eaten their lunch. After they had gone up the trail a ways, he asked if he could go back and get it. The leader told him he would go back with him in a minute. The boy went back without the leader. The log they had crossed over the creek earlier now had water flowing over it. Apparently he slipped on the log, hit his head on a rock as he fell into the creek. The creek drops about 300 feet in about a quarter of a mile.

They had found him drowned and brought him to Driggs to the mortuary. No sign or bruises or cuts on his body. It was most sad for the mother and family. I was glad that I had made it a practice to have my pack ready for such an event although I did not get involved this time. There were times when the Forest Service came to us when I was running the Climbing School and had us assist in getting someone out of the back country. It was nice to have the experience and expertise to assist, but glad that we didn’t have to any more than we did. We had word of a fellow camped at Bench Lakes that was supposed to be a diabetic and in trouble.

The lodge took us up the lake halfway in a boat and we climbed up the face to the trail got him and brought him back down the slope in a rope stretcher, when he got off the boat at the lodge there didn’t seem to be anything wrong with him. They called us once to go to Mount Cramer where someone was supposed to have fallen 75 feet and they thought we might have to do a technical rock rescue off the face. We got ready to face that problem when word came that he was off the face and we didn’t need to even help. I would lots rather be prepared to handle something rather than get into a situation that I couldn’t handle.

Grand Teton

The first time I did Grand Teton, Carol, Bonnie, Willard and Sherie and I went over to the Tetons so I could climb the Grand. We camped at the Jenny Lake Campground and I went over to the Exum School to make the arrangements for me to climb. Jake Breitenbach was there and was taking a group up the next day and was happy to have me come along. We left the next morning and hiked up the trail to the mouth of the canyon. There was not much of a trail up through the boulder field in those days. As a matter of fact, there was more open grassy ground along the stream in those days. There was no trail at all up out of Garnet Canyon to the Petzoldt Caves. Paul used to camp up there and wait for people to come up and he would take them on up to the summit. There were worn spots in the moraine that resembled a trail, but nothing you could call a trail. We slept in the hut that night and had hot chocolate and whatever we wanted for breakfast. Supper had been a conglomeration of soup each of us had brought and mixed together to eat.

We got up early went up to the dike, up through the eye of the needle and then on up to the upper saddle. We roped up there and worked the belly roll and the Owen Chimney to where the rappel was setup. We climbed on up the slabs of down-sloping rock to the summit. When we got to the top of the Owen Chimney, I discovered that I had dropped my camera. Jake didn’t think there was any chance of finding it, but he went back and came back with it. He had let me be the leader on the second rope team during the climb. We spent some time on the summit then came down to the rappel spot. The Owen Chimney was more difficult going down than up. We had plenty of time so Jake let us go up to the summit of The Enclosure.

I found the spot where the Indian maiden had supposedly spent the night from the story told me at scout camp. It definitely was a rock wind break with sand in the bottom. Jake told us about being hit with lightning while on the Grand once. I remember it rained for a while on the way down from the lower saddle and how my toes were jammed against the toe of my boot and wore blisters on every toe. We walked all the way across the meadow to the Exum school office. Even though we were all tired, because we got down early, no one was there to meet us. I was happy to be back with Carol and the kids.

The Grand Teton. Lyman Dye Photo

The next time I climbed the Grand I did it with Wayne, Art and James Reed. We talked with Al Reed (no relation to James) at the lower saddle about waking us the next morning when he took off with his group to the summit. We caught them at Wall Street as they were roping up. Al said we could pass them anytime we wanted. I took it as he didn’t want us using him as a guide. When we got around the corner, I went up the Golden Staircase and he was belaying at the top. I kind of surprised him. He wanted to know what I was doing. I said I was passing him.

I remember how scary the friction pitch looked to me, but I was not about to let it beat me. I got about halfway up the pitch and really wanted something to grab onto when I found this little saddlehorn piece of rock to latch onto. That was all I needed, it really did the trick. We summitted and were just getting off the rappel when we heard the Exum group summit.

Lyman Dye Photo

I remember the group that Vaughn Howard helped me take to the summit. He was just 16 years old and took the friction pitch almost with his hands in his pockets. It was impressive and the Exum guide climbing behind us thought so as well. They had tried to outrun us coming up the trail the day before, but couldn’t get ahead of us. They even took a shortcut in the trail to no avail. They made some snide remarks about the way some of our packs were arranged. I found a cave back in the boulder field at the start of the moraine where the stream comes down from the Tepee Glacier that we used quite often when we climbed the Grand. Art, Wayne and I almost climbed the Grand by that route at night once it was so clear.

One time we got up to the saddle early ahead of anybody and hid out in the rocks until the ranger came up and did his permit check and left. We came down, set up our tents and spent the night. The only room they had for climbs the day we registered was at the platforms and we just didn’t want to be that far away. We ran a risk but I thought we could talk our way out of any problems as there were people that had turned back during the day. There was plenty of room on the saddle for all of us.

I remember finding spots in the caves over on the West Side of the saddle to weave our bodies into for sleep. I remember times when the thunder and lightning was scary as storms rolled around us in the evening. The biggest hazard of all on the lower saddle was the marmots running over you in the night and eating holes in things to get to your food during the day.

The first trip I took a paying group up was a Laurel High Adventure Group. There were 12 of us to the saddle. The woman leader and her husband decided they couldn’t do the climb beyond the saddle. He raided some of our packs for something to eat during the day. When we got down from the summit to the saddle it looked like we had plenty of time to make it out before night. It took me 3 hours to get the woman leader down to the mouth of the canyon. I had to place almost every one of her steps coming down off the saddle.

It was dark when we got to the trail and had 4 flashlights for the 12 of us. I spaced the flashlights along the group with the instruction not to use them unless absolutely necessary. I had a small Swiss bell on each corner of my pack that rang as I walked. They were instructed to follow the sound. We could barely see the trail. I would pass back by word of mouth notice of the bad spots on the trail. We got them all out safe and tired about 1:15AM the next morning. It truly was a high adventure for them.

I don’t know how many times I have been up the Grand but each time was a wonderful experience. Some years ago, Wayne and his son went on a trip up there with me and Wayne mentioned that I went up the mountain just as fast as I always did, but I sure had slowed down coming off. I think of all the times we raced each other down slopes at breakneck speeds and it sure has taken its toll on my knees. They get to really hurting at times, I can hardly take another step on a rocky trail.

Lyman Dye Photo

I took a group to the Grand Teton one Labor Day. The conditions were so bad that even going up the snowfield below the lower saddle, the wind was whipping the kids around, even knocking 2 of the boys off their feet. We ran into 3 fellows at the base of Wall Street who had never climbed a mountain before. They had done some bouldering in Colorado in their hometown but had never been on a mountain. I have no idea how they got by the Rangers or even if they checked in. They only had one rope and were planning on tying the rope off at the rappel and then pulling a 1/4″ cord that would untie the rope after their rappel. They were not sure of the route from the summit down to the upper saddle.

I said they could follow us if they wanted to, which they did all day. My second rope team leader got hung up above the friction pitch and I had to go back and rope him out of the pitch. On the summit, the 3 guys talked with my group and ask if they thought I would let them do the rappel on our ropes. When it was my turn to come off after everyone else was down, I started down and my rope didn’t want to feed very well, so I jumped off one spot and hit the rappel as hard as I could and it started to flow. I gripped down with my gloved hands but the gloves and rope was so wet and sloppy that things were not slowing down much. I finally got things slowed down and in proper order about 20 feet before I would have hit the ground. Everybody was really concerned as they watched me. I had dreamed about the rappel the previous night and so was extra attentive to what I was doing. I led them down we did the rappel and got back to the lower saddle at sunset. My assistant needed to get on his way home that night, so I sent him down with the 3 guys to the meadows so that he could send word home what our situation was.

The next morning we woke up to 6-8″ of new snow all over the range. The sunrise was fantastic with the fresh snow and gold from the sunrise. We decided it would be just as easy to glissade directly off the saddle rather than down-climb the wall. We all made it down to the meadows and found that the guys had decided to not break their camp because of the storm and sit it out until morning. We all came out in much better spirits because the storm was over and the sun was out. My wife and others at home were worried because we were all supposed to be home the night before. Carol had told those who called that she was sure everyone was safe that we had probably run into difficulty. I felt sure if we hadn’t been there those 3 guys would have died on the mountain.

Another time we ran into a group on Wall Street that were not well prepared for the climb. We offered to help them and got them to the top and back out safely with us. I got a package several weeks later from one of the group with an official hooded sweatshirt from his university. That was pretty nice and thoughtful of him.

Mount Moran

The first time we went to Mount Moran, we went up the Leigh Lakes Trail and there was a lot of downed timber out on the flat. We crossed the creek and worked our way up under Drizzle Puss for our camp. We went over a ways from our camp and we could see the falling ice glacier. I remember waking up several times during the night hearing the chunks of ice roaring down the canyon. We left one rope at the notch as the guide book suggested and did the CMC route which follows the black dike. The rock was solid, but rather down-sloping. The summit was a surprise as it looked like a big ant hill. On our way back across the creek on our way out, we decided to wade the creek as the log crossing had been washed out. I took my boots off and intended on throwing them across but didn’t swing them far enough and they landed in the creek. I very quickly jumped in and got them before they got carried away out into the lake.

Lyman Dye Photo

The next time we went over to do Mount Moran, we thought we would do the Skillet Glacier Route or the Three Glacier Route out on the West Side. We checked in at the Ranger Station and were questioned if we had looked at the peak this morning. It was suggested that we might want to take a look before we decided what route we might want to take. We drove up and took a look and quickly decided the mountain was not to our liking that day. The entire face of the peak was like a gigantic mirror. It was completely covered with verglas. We wanted no part of that scene! We went back to the station and decided on going up into the basin and did the North Face of Mount Spaulding, Cloudveil Dome and Nez Perce. The ranger informed us on checking out that we probably had put a new route up Mount Spaulding. Whether we did or not, we never checked it out further.

The last time I was on Mount Moran, I took Frank, Lois Haderlie and son up the Northeast Ridge. We took a boat across Jackson Lake to facilitate the climb and back across the lake after the climb. The route was not difficult. The interesting part of the trip was when we got up to the site of the plane crash. We rummaged around in the debris and found parts of shoes, Bibles, buckles and other things. The metal parts of the plane on the ridge had been mashed flat from the weight of the snow over the years and, of course, there were parts of fuselage and stuff over the side in the gully. We did not check those out. It likewise was flattened by the snow and crash. I understood that someone beat the rescue party up to the wreckage and took what they wanted. The peak was closed for 5 years after the wreck to allow bodies to decompose and clean things up a bit. The Haderlies were likewise surprised at the nature of the summit, looking like a giant knob of an ant hill. It has been the weirdest of all the summits I have been on.

More Mount Borah Adventures

Mount Borah became pretty much the warm-up climb each year. After the first climb in the Summer of 1959, either Mount Borah or King Mountain, depending on the nature of the Winter and snow conditions in the Spring. We had tried an ascent in the early Spring from several different routes. One year we thought it best to stay out to the south of the Southwest Ridge, thinking the ridge would be less difficult. The terrain encountered getting to the upper plateau below Chicken-Out Ridge was not worth the switch. The snow on the lower reaches of the peak are not so difficult in the morning, but warm rather quickly and so on the descent breaking through the surface and wallowing in snow up to the waist becomes pretty general.

Mount Borah. Lyman Dye Photo

The Southwest Ridge to the false summit is generally windblown enough that the ridge can be climbed without too much difficulty. The area known as The Icicle is a snow bridge in early Spring but becomes a prominent notch in Summer, with steep angle snow slopes descending on either side of the apex, needing caution when crossing in the Summer. We always found the upper slopes with compacted snow tiring, but always passable. There were times the snow depth was mid-calf, but nothing like the hoar-frost conditions that were on the mountain the days of the search for Vaughn Howard and Guy Campbell.

The 2 climbers we put on the upper saddle to see if the climbers had made it to the summit were confronted with horrific conditions. The windblown ice was about a foot thick and exploded under the impact of the ice axe while cutting steps. I have never seen the likes of those conditions on any peak I have climbed. The ISU Outdoor Group that spent the night in the bowl beneath the summits said the temperatures reached -50 degrees that night. It was not a pleasant place to be on the mountain at any time during that search effort.

The Copper Kettle in Mackay and a restaurant from Challis were kind enough to bring us hot meals during the course of that effort. We had facilities set up on the flat near the Smith Ranch from which we operated. Mike Howard and I were taken by pickup over into the Pashimeroi Valley and we came back across the North Ridge to camp trying to cut the trail they may have taken. We saw a lot of wild country but did not find any tracks we were looking for. The only signs any of us found was their camping spot in the pocket on the Southwest Ridge. The dogs Bonneville Search and Rescue brought in would move out to the north past the camping spot, over the lip toward the North Ridge then seemed to lose scent and turn back. It was not until the following Fall that their bodies were found partly covered with snow below the slope on the North Ridge. It seems that they were caught in an avalanche on the face and remained buried those 11 months.

We were coming off the North Ridge one time descending the fairly open face. There were trees scattered around in the shallow bowl and we were descending in a straight line down the bowl when all at once we heard this whooooosh of air and the snow in the bowl dropped about 3-6 inches. The slope had come very close to avalanching, but I think the trees on the slope were the tying force that stopped it from going. That’s when we all gave a big sigh having been that close to a very dangerous situation.

The one Winter ascent we did on the 30th-31st of December. The wind was blowing pretty badly on the ridge, close to 30+MPH, the temperature was -18 degrees. We all had balaclava helmets and down jackets. I pulled my balaclava helmet off while we were snacking in a sheltered spot. We were all surprised to find white spots on my nose, cheeks and two streaks across my neck. I had been in the lead and had not been too careful about shielding my face from the impact of the wind. Needless to say, we were all more careful having learned from that experience whenever we encountered those conditions again.

Lyman Dye Photo

On July 7, 1969, we decided to go over to Mahogany Creek in the Pahsimeroi Valley and do the East Face of Mount Borah. We went over Doublespring Pass to Rock Creek and up past the outrigger cabin as far as we could, then up the Northeast Ridge of Borah Peak to the face. The face was upper Class 4 with the most difficult pitch being on the cliffs on the North Side which was low Class 5. We stopped at a notch on the North Side of the summit to enjoy a snack and things looked rather simple the rest of the way. I put my hardware away in my pack and started up the face again. I got up about 40 feet and needed something to jam into a very narrow crack on the rock above me. I could get the tip of my finger to the edge of the crack, but not into it. I tried a couple of times, but to no avail.

I was going to climb back down and decided that was not a go. I remember my one leg beginning to quiver like a sewing machine needle, dancing up and down. I would love to have a blade piton or something to shove in that crack, but it was in the pack on my back. I yelled back down to Art and Wayne that I was in trouble. There was not much they could do but watch me fall or make the move. I decided that I didn’t have a choice and lunged for the crack and ultimately over the crux. That was a scary few moments that seemed like a long time, but the climb was easy from that point on. I do remember getting sick on the way out later after getting back to the car. Apparently my stomach didn’t like the apple and sandwich I had on the summit. I had that happen several times on a descent–getting a little upset and having to throw up.

One late Spring morning, I had left Idaho Falls on a Friday evening planning on going over to check out snow conditions and things at Redfish. I had been late getting away from Idaho Falls and felt a little drowsy so when I got to Mount Borah, I decided to pull off and spend the night. I got up early the next morning and, not having any client or deadline to be at Redfish, thought I would take a look at the North Face of Mount Borah. I had my crampons and ice ax and other equipment so thought it was a good time to take a look. It did not take me long to get over the ridge and get out on the face. I knew it was not a good idea to be doing something that I had not told anyone I was going to attempt, but decided to be extra careful and see what would work.

Lyman Dye Photo

I made sure that each step I took was planted and solid, knowing that a slip could be very life-threatening. I was feeling strong and confident, so I continued getting higher with each step. The final couloir to the summit was the most difficult and was climbed with ease. I came back down to a notch in the ridge with a nice couloir leading down into the basin between the Southwest Ridge and the Northwest Ridge. I saw a large boulder there in the notch and rolled it into the couloir. I watched as it rolled down and started an avalanche that eventually stopped down in the basin. I figured that the couloir was safe enough to descend, so I jumped in and glissaded as far as I could. It was a much faster trip than the climb up. I continued on back to the car and returned to Idaho Falls rather than even going on over to Redfish.

Mount Borah has always been a rewarding climb, one that is safe with some difficult pitches and with enough distance and toughness to make it an ideal conditioning climb to start the season with. I took the boys from our ward in Ucon to the summit one Summer. Jon Holst was the Young Men’s President at the time. He and I pretty much stayed together over the whole trip. The boys were finding it difficult to stay in line so when we got above the false summit, I turned them loose to find their way to the summit. There were three 20-year-old college kids from Pocatello that had passed us earlier. They began stopping to rest whenever we did. They would stop after we did then take off when we would get up to go again. Jon and I were both feeling a little taxed lower, but I caught my second wind above the saddle. I poured on the gas about 300 feet below the summit and went right on by them. They stopped Jon and wanted to know how old I was. They found it hard to believe that this 68-year-old man had beaten them to the summit.

I remember years ago when my youngest son Gregory and I climbing Mount Borah in early Spring. We had spent the night out in the bowl below timberline on a shelf where there was water. I rope him up on the ridge and moved on to the summit. I was in snow up to mid-calf and he was in up to his waist behind me. We rested on the summit, enjoyed the view and got ready to go down. I told him to go down first and he hesitated and then started to cry. I asked him, “What was the problem?” He replied that there was no way he was going to be able to protect me if I fell. I was too heavy for him. I explained that I was behind him to protect him as I had been on the ascent. With a big smile on his face and the tears gone he replied, “Let’s go.” All he needed was the assurance that I was still in the lead although not in front. What a wonderful lesson that was to me to understand that sometimes we need to define to others what is actually taking place.

Warbonnet Peak

My first trip into do Warbonnet Peak was with Art Barnes. Neither of us had been that deep into the Sawtooths before and it was virtually new ground for the both of us. We left the Redfish Lake Lodge, following Bench Lakes Trail up Redfish Creek to the lakes below Baron Pass. There is a beautiful place to camp between two small lakes on the East Side of Baron Pass below Le Bec D’Aigle. The one lake is right along the trail to the pass and the other is about 200 yards to the east, kind of hidden from view by some pines. This spot became a choice place to camp over the years as we made our many trips into the Sawtooths. There is a small group of about 5 pines (2 of them bigger than the others) and a flat slab embedded in the ground between the 2 big ones. We used the slab as a tabletop for our stoves and cooking pots.

Warbonnett Peak. Lyman Dye Photo

The lakes, of course, provided us a place to clean up and swim as we desired. I remember one time having a group in there on a trip and letting the females choose which place they wanted to take for their swim. They elected to use the one next to the trail and none of us considered the possibility of hikers coming along with them in there. The thought never crossed our minds that a couple of them would decide to go in naked. It was one of those choices that proved to be a little touchy when 4 hikers came along. All of the gals stayed down in the lake while they went by and then accused me of laying a trap for them.

Art and I got up the next morning and went over Packrat Pass into the Feather Lakes area and climbed up to the notch between Lionhead and Warbonnet Peak. I had read the accounts from the Iowa Mountaineers and Louis Stur, so felt I could find the route. We got up to the chimneys below the staircase. Louie had written in his account that one was too small, and he had difficulty in moving up the other one because of his waist size. I found another spot that I felt would be easier to do than the two chimneys. I got partway up this cliff and wanted to move to the left.

I realized that this would require me to rotate my body while rolling to the left on my handhold. We called it the “rolling donut” move! It was a ticklish tough move but it did get me where I wanted to be, above the chimneys in question. The friction staircase was a beautiful move up to the notch where we got a good look at the summit fin. It looked good and spooky. I stepped out onto the small ledge and then moved up the wall about 40 feet to a belay point. The move from there to the summit was pretty much a friction pitch–touchy and thrilling. The view from the summit is spectacular.

Some years later John Johnson and I went to do it in Winter on the 30th of December. We actually went 2 different years to do a Winter ascent. The first time, we only made it to the upper end of Bench Lakes and it snowed during the night. We woke up in our tent with the top resting on our faces. We skied back out and got to the lodge to find my car still parked at the lodge. We had told the caretaker to drive it out if it started to storm. He told us later he had tried to get his truck out first and it ran out of gas. It was snowing so hard and the wind was blowing so bad, after trying for 2 ½ hours and only getting the car about a hundred yards, I called the Forest Service to see what they could do for us.

They ended up blading 6 inches off coming in and the same going back out in order for us to get out of there. Once the T-bird got moving it was okay, but it sure didn’t want to buck snow until it got some speed up. We drove up to Obsidian and got a bite to eat before we came on home to Idaho Falls. The snowplow operator came in while we were finishing up our dinner and said we better get rolling if we wanted to get over the summit before it blew back in. We took off and the windshield wipers quit about a mile up the road. I ended up driving across the pass counting on the wind to keep the windshield cleared off.

The second time Mike Howard and I went in to do the Winter ascent, we crossed the lake as far as we could and then finished on the Bench Lakes Trail to the inlet and on up to below what trail we could find to Baron Pass. I had borrowed a radiophone from the Forest Service so we could tell them if we had difficulty. Our original plan was to make a second camp over in the Feather Lakes area, but we decided to try to get to the summit and back in one day. We left our tent early and things moved along really well. We had taken along some extra things in case we had to bivouac. We had discussed my maybe having to tie my wool stockings to my feet to do the staircase in order to do the friction pitch on the summit.

That was somewhat of a pipe dream, I think now, but it was something that had gone through our minds. The staircase was blown and iced up a bit, but I managed to make it up to the notch and out onto the ledge. The summit looked like it was free of snow and ice so up I went. The weather that day was beautiful–cool but certainly not as bad as it could have been. We got back down to the saddle and called the Forest Service to tell them that we were off the mountain and heading back to camp. The trek back up the canyon was not as easy as we had anticipated and the sun went down and began to get cold long before we wanted it to. We had about decided to dig ourselves into a comfortable spot when the moon came out and it was almost like daytime. We slowly moved on hoping not to miss our camp in the night. We came right in as if we had been guided on a string to our tent. We both were mighty happy to climb in our sleeping bags instead of trying to stay alive in the cold.

The next morning, the noise of the radio on squelch woke us up with its squawking. The battery had decayed off during the night in the cold and we had no idea how long it had been that way. The rest of the trip out was fantastic–downhill, so to speak, with the glow of doing what we came to do. We dropped off the radio and thanked the Forest Service for its use. They were most happy to have it back and know that we were safely out of the backcountry. I took Willard, Bonnie, Sherie, Teresa up Warbonnet Peak as a family once, going in over Packrat Saddle and returning up Baron Creek. We had to rush our time a bit on that one because of the incoming storm, so the kids were not allowed to spend much time on the summit. I have always enjoyed my trips into Warbonnet. We found it very refreshing (sometimes with a group) to drop down to Feather Lakes and take a cool dip in the lake before returning to our campsite.

One year (1973 or 1977), we decided to do the North Face of Warbonnet Peak by a new route. Quincy Jensen from KID Radio was going to do a movie of our climb. We flew in from Stanley and did a fly-around a few weeks before we were to do the climb, looking at the mountain and getting some good pictures of the terrain. Quincy brought along a 900mm telephoto lens so he could sit over on the Lion Head Peak and take pictures of us as we climbed.

Lyman Dye Photo

I took a movie camera with me for the close-up shots. We went up the North Face with the intention of doing the long friction pitch to the summit. We got up to that location of the climb and could not see a way to get started on the pitch. We moved over into the great crack that splits the peak and climbed upwards through the 40-foot crack to the East Side, exited up a difficult pitch and ascended the summit block from the east. Quincy bumped his zoom lens and it fell down into a crack. We had a difficult time getting it back out. We were worried that we were not going to be able to retrieve it for him. I have a 16mm film of that ascent hidden away in my stuff somewhere.

Lyman Dye Photo

I have always considered Warbonnet Peak to be the Grand Teton of the Sawtooth Range. I know there are difficult pitches on Elephant Perch and it has been climbed more but, to me, it is the Granddaddy of the Sawtooths. Paul Petzoldt brought the Iowa Mountaineers in as their guide in 1947 and was greatly impressed with the difficulty of its only seemingly climbable route to the summit. The view of Warbonnet Peak from any angle presents a very impressionable summit with its overhanging fin with about 1,000 vertical feet to the valley below.

Chockstone Peak

Chockstone Peak is in the upper end of the Redfish Creek valley almost to where the trail turns east to Cramer and the other fork heads up the switchbacks to Baron Pass. It has a very prominent large boulder suspended between the 2 summits that make up the peak.

The first time I climbed Chockstone Peak, we approached it from the southeast then up moderate rock to the summit blocks. When I took the Mazamas up, we approached it from the north and ascended the West Wall of the East Pinnacle of the peak. We started up that wall well before we got under the chockstone. I have never attempted the West Wall of the West Pinnacle. I do know that one needs to be careful on the rappel so as not to get the rope hung up and have to cut the rope free.

Guiding Expeditions

I took a group of climbers on a 7-day expedition once up Redfish Creek to just below Mount Cramer where we made our camp. We climbed the prominent crack on the north end of the West Face of Cramer to the North Ridge and then to the summit. We also did the North Crack on the Red Bluff and did the short climbs of the Sentry, Coffin, Arrowhead, Sevy , the Owl and the Finger of Fate from this camping spot. We moved over to the camp below Baron Pass and did Packrat, La Fiama, Mount Underhill and the Mayan Temple.

I have taken groups in on similar 7-day expeditions going up Redfish Creek to the camping spot at these 3 Alpine Lakes. On these trips, we would often climb Verita Peak, Cirque Lake Peak, Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner, Mikes and Tilted Slab Pinnacles, Lionhead, Perforated Tower, Tohobit, Packrat and Le Bec d’Aigle. On other 7-day expeditions, we would go up Fishhook Creek and camp at Stephen Lakes. We would do Fishook Spire, Braxon, Rotten Monolith, Rothhorn Spire, Quartzite Peak, Schwartz Pinnacle, Mount Ebert, Eedahow and Horstman. We would often go up the Marshall Lake Trail and climb up the headwall between Mount Williams and Thompson Peak, make a high camp and do both of those peaks as well as Mount Bush, Mickeys Spire, Annas Pinnacle, Fishhook Spire, Mount Heyburn and others that the group might choose. There were times we would move on over to the 3 Alpine Lakes camping spot and do climbs on the Verita Ridge.

On occasion, we would go to Lower Redfish Creek and do Braxon, Mount Heyburn, Quartzite, Red Sentinel, the Grand, Small, Black Aiquille’s, Rotten Monolith, Elephant, Eagles, Goat Perches, Chockstone, Redfish Point and the Grand Mogul. There were a couple of times we went all the way into the Feather Lakes below Warbonnet Peak on expeditions and did climbs along the Verita Ridge, Mayan Temple, La Fiama, Packrat, Tohobit, Underhill, Warbonnet, Verita Peak, Mount Regan, McGowan and Baron Spire. We never seemed to run out of variations of peaks to climb on any of our expeditions. The storms (as they came into the area) generally were of short duration during the Summer and the lightning/thunderstorms were always fantastic.

Guiding the Iowa Mountaineers and the Mazamas

I was the chief climbing guide for the Iowa Mountaineers during one 2-week outing into the Sawtooths. I was kidded one day by one of their climbers about my rating for several different climbs at about 5.2 or 5.4. I guess he thought that every climb I had scheduled was either of those 2 ratings. On one of the climbs, he complained that the rating was not as high as it should have been. Ratings in my way of thinking sometimes reflects the sharpness and ability of the climber on any given day. There are some days that a person could do a very difficult pitch with ease and another day it might be all he can manage. It is merely an estimate by an individual climber on the day he rates it. It also does not reflect the ease with which one handles certain holds in comparison to someone else.

I have conducted extended day outings for the Mazamas of Portland, Oregon on 3 separate occasions. Two of these were in the Sawtooths and one in the Beartooths in Montana. Prior to my guiding for the Mazamas, the first time there was some discussion about my being selected, as most of the people did not know me. I did not know anything about it at the time but, after the outing was over, it came to my knowledge through a special friend. There was never a question voiced in my presence of anything but of a positive nature to any of my guided services. Well, there was one time it was mentioned by a climber that, “I was no Lute Jerstad.”

This individual had been into the base camp of Everest on one of his guided trips and this individual complained that Lute had never treated them as I had treated them in the Sawtooths. I replied that, “You are not paying me $3,500 to coddle you either.” I had pushed them a little hard coming down through some rough country to the trailhead and she was tired. They all plopped down and hardly moved for about 20 minutes. There are not too many things that make Mazamas move fast. Rudi Kaufmann, one of our Swiss Mountain Guides in Europe, mentioned two things that made them move fast–lightning and rattlesnakes (see my writeup of our Alps trip).

The first Mazamas outing at Redfish Lake, we set up camp at the inlet campground. This required the supplies to be ferried over by boat, and any climbs done on the fringes of the range required the climbers to be ferried to and from the campsite from the lodge wharf. We sent a group out to climb Invisible Peak one day, which was an easy climb. They had some difficulty and did not get back by dark. One of the climber’s wives came to me and wanted a search party organized to go look for them. We, of course, did not know what their status was. I informed her that to send a party across the lake by boat in the dark was out of the question. If we were to set out, we might miss them at any given number of places and set others at risk as well. I told her if they did not come back in the morning that we would go after them. I even told her that very likely they were spending the night in a nice warm bed in a Stanley motel while she worried about them. The next morning they came across the lake by boat just as we were finishing breakfast. They had spent the night in a motel and were just fine.

We climbed the Grand Mogul, Elephants Perch, Goat Perch, Eagles Perch, Chockstone Peak, Redfish Point, Packrat, Warbonnet Peak, La Fiama, Thompson Peak, Schwartz Pinnacle, EeDaHow Peak, Elbert, Hortstman, Heyburn, Fishhook Spire, Underhill, Finger of Fate, Invisible Peak, Mount McGowan, Grand and Small Aiquille, Red Sentinel, Le Bec d’Aigle and Decker during this outing.

Le Bec D’Aigle

The climb on Le Bec d’Aigle was up the North Ridge and was the first ascent by that route, very impressive in a picture. We also put up a new route on Mickeys Spire and new first ascent route on Fishhook Spire. One of the leaders chose to take the new route up the West Crack. I took the rest of the group up the standard route. We were partway up the peak when he yelled he needed help. I left my group and got into a position where I could give him a upper belay over the one pitch so that they could finish their ascent.

The climb we made on Chockstone Peak was also a new route as far as we know–out on the wall on the East Side of the peak. When we came back down from the Fishhook Spire climb, the the group could not figure how I could bring them through that thick timber and underbrush back so close to the trailhead. I do know that when we broke through the underbrush and saw the creek and trail, they were mighty happy. No one had to ask them to put down their packs and get a cold drink of water. They were like a worn out herd of sheep sprawled out on the ground every which way for about half an hour.

Carol and the kids came to this camp with me and we all had a glorious time. There were some young people hired to do the kitchen cleanup and dishes. They also had professional cooks that provided the meals during the outing. I spent some time with some of the young people during the outing. They were amazed with the fact that I was willing to sit down and listen to them. There was a couple of them that were so lonely for attention, it was sad. They commented several times that they wished their folks would visit with them the way I had. I have always been a part of the church and its programs and so it was a witness to me of God’s pattern of things for his children. I have often wondered what happened to those kids when they got back home. We shed tears when the outing was over and it came time to go our separate ways.

Guiding the Mazamas in Montana’s Beartooths

The second Mazamas outing in the Beartooths near Cooke City, Montana was conducted in much the same way. I spent a lot of time in the evening chatting with the cooks and their help. During the outing, we sent a group of climbers out to do the repeat climb of Zimmer Peak. The leader got to feeling ill on the return to camp and was sent out to Yellowstone Lake Hospital. He came back and was required to stay in a motel in Cooke City. He later ended up dying from a heart attack. He had come on the outing knowing he had a heart condition and had told no one about it. Joan Shipley and her mother came to me on behalf of the group and asked if I might conduct a religious service one evening for him on behalf of the group. I was a little scared at the request but drew on my mission experiences and the truths of the gospel to conduct that fireside service in his memory.

We put up a new route on Granite Peak on this outing. We climbed up a crack on the face going in past Sky Top Lakes. My assistant leader had brought small flags to mark the route of the ascent. It rained for a few minutes when we were on the ascent and so on the descent there were periods when the fog would rise up along the face and we could not see too well. It was great to be able to look for those flags and thus find our way. The flags were a common thing with snow climbing in the northwest, but it was something I had never done on our peaks. Being in strange country, it proved to be a good thing as it certainly eased our descent problems.

We had been out climbing one day during the second week of the outing and some of us were chatting in the cook tent. The question was raised about what we could do tomorrow and I replied that I don’t think you are going to want to do any of the climbs we have scheduled because it is going to snow. They thought that comment rather strange, but the next morning we had 6 inches of snow on the ground as a testimony of my knowledge. We elected to break camp as we had come in by 4-wheel drive and, as it was, we just did get everyone out before the snow got too deep to travel the trail. I had a jeep that had been modified into a small pickup at the time and had a little difficulty getting into the camp at one spot where it crossed the creek.

I managed to get back across okay with my stuff intact, but it got really tough for the last loads with the pickups hauling the Mazamas gear out. It was a wonderful trip in spite of it being shortened. During the course of the outing we climbed the following: Courthouse Mountain, Sawtooth Mountain (11,489 feet), Wolf Mountain, Glacier Peak, Mount Villard, Granite Peak (12,799 feet), Mystic Mountain(12,073 feet), Iceberg Peak, Mount Wilse and two climbs of Mt. Zimmer (11,550 feet). Mrs Coombs flew her private plane over and landed at the Rigby Airport once, bringing her daughter Joan Shipley to see Carol and I. We stayed at their house once when we visited Portland for a Mazamas annual banquet.

Guiding the Mazams on Borah

I also guided 2 Mazamas climbs on Mount Borah. The one I remember well was camping at the Mackay Dam Campground. The participants drove in about 4-5PM the day before. There were some that wanted to drive into Mackay and get something so I showed them the way to town. We ate at the Copper Kettle which was always a good place to eat.

The next morning, we were up early and climbed to the summit without incident. The afternoon sun had heated up the snow on the mountain by the time we got to Chicken-Out Ridge on the way down. It was tedious to break through in places to mid-thigh and it got to be quite a grind getting back to the base. There were times that choice words could be heard about the snow conditions. I am sure that was long forgotten on the way home to Portland having achieved their wanted peak. The evening after the climb was spent savoring a steak dinner and good conversation between all who were there. I gained some great friendships with members of the club over the years. Peg Oslund, Don Eastman, Joan Shipley, her mother and sister, and Bill Pratt were the choicest.

Mount Heyburn

The first time we did Mount Heyburn was part of a scout activity from the Arco Ward. Wayne Boyer and I left the rest of the boys doing their things during the day and he and I decided to climb Mount Heyburn. We went up Redfish Creek beyond the inlet campground to the slide area below the Heyburn Basin. We went up into the basin and took a look at the cliff formations to the south of the summit.The higher we got up to the ridge, the more rotten it became. I found out later that was the route of the early ascents. On what has become known in the Sawtooths as “ball-bearing granite.” We didn’t like the look of things above us, so we crossed over the ridge onto the West Side and saw the large crack in the wall known as Stur Chimney. This chimney is about 300 feet in length and has a couple of boulders that seem to block the ascent, but can be traversed out on the wall or working over.

Another closer view of the Stur Chimney from the base of the slabs that lead up to it.

I took a prospective guide and a client up Mount Heyburn one time, made the ascent and rappelled down the East Side. In the Summer time, this is a loose scree slope and one needs to be very careful. There are places the loose scree is laying on top of smooth slabs and you can really go for a ride. I warned the two of them as we were going down the basin. They seemed to be trying to race each other and I yelled at them to knock it off. They came to one of those loose spots and the client went down in a heap. We got him up and assisted him out to the boat and later to the hospital, where it was determined he had indeed broken his leg. He did not lay a claim against the guide service because it was his fault as he had been warned.

One time, Art Barnes and I had climbed Mount Heyburn and came down the same way only in the Spring. The snow was beginning to sluff off in surface slides and we were careful as we descended. We came to the notch out of the upper basin and could see that there were several funnels feeding into the notch and then fanning out after they got through the notch. These slides were coming down about every 10 minutes. We decided I would jump in the main slide ditch after the next slide went through and then Art would jump in after the next one. I jumped in and had gone about 30 feet when I got hit from behind with a powerful force of snow. I tried several times to put my ice axe in the side of the ditch and pull myself out of the trough before I finally got out. I shook myself off and looked up the slope to see where Art was. He finally came.

Stumbling down the runout. When this massive slide had come through, it had knocked him off the mound he was standing on and he finally swam out of the swarming mass. He lost his wrist watch and ice axe in the process. We were glad it had not been anymore detrimental to us than it was. When we got back home to Arco and reported the losing of the ice axe to my wife, she thought we said Art had losts his eyesight. She was really concerned for him. One time we went to climb Heyburn up that East Basin and crossed over to the West Side and decided we didn’t have time to do it before we needed to get back to camp. We had been roped up and, rather than take the time to coil up the rope over my shoulder, I decided to pull it for awhile over the snow. I got partway down the slope, hit a hard ice spot, lost my footing and started to slide. Every time I planted my ice axe to self-arrest, it seemed the rope hung up and pulled the axe out.

Wayne yelled that he would grab the rope and stop me, but I told him no because I was afraid that if I went over the cliff below that it might slam me back into the cliff. I went over the cliff of about 15-20 feet back out onto the snowfield before I got stopped. I learned from that experience it is wise to take the time to recoil the rope, it is safer. One time while the others were resting on the summit I down-climbed out on the North Face to see what it looked like from the upper end. I moved around this boulder on a ledge it looked like it was part of the ledge and so I was not concerned. I worked around it and went down about 100 feet and then came back. When I came back around the boulder from below, I guess I was holding on to the boulder more than on the descent because it swiveled with me as I moved around the corner. I took that as a wise lesson to be attentive always no matter what your climbing around or on.

It was a rather discomforting feeling to have it move so freely on the return climb versus going down the pitch. Literally it felt like it was on ball bearings and it would not have taken much for the two of us falling off the ledge embracing each other. Later that Summer we decided to do the North Ridge and put up a new route on Mount Heyburn, just around the corner where I had down-climbed. We ended up moving west of the North Ridge partway up the face and into a crack to the north of the Stur Chimney. The rock was fairly solid but there were places where it got rather thin. It was an exhilarating climb and one of the most enjoyable on Mount Heyburn.

I have only repeated that climb once since. On one of the early climbs we did on Mount Heyburn, we went up the North Couloir between the two summits on snow. There was a large cornice in the saddle above us that caused us some concern as we climbed. We had to carefully chop our way through to get into the saddle. We finished up on the East Side we would normally rappel down when climbing the Stur Chimney. We duplicated the route used by the Iowa Mountaineers when they made their first ascent with Paul Petzoldt. We however did not find it necessary to do a shoulder stand as they had done to get started on the wall.

Thompson Peak

The first time we went in to climb Thompson Peak, it was early Summer and there was still quite a bit of snow in the upper basin. We went up Fishhook Creek farther than we needed to have before we turned to the west to make the ascent. We encountered some slabs that gave us a chance to practice our friction-climbing abilities. We passed Mount Bush on our left and Anna’s on our right and headed up to the East Ridge of Mickey’s Spire. We climbed to the saddle between Mickey’s Spire and Anna’s and the looked off to the northwest to see the summit of Thompson Peak.

The snow across the North Face of Mickey’s Spire was as smooth as could be, not a track. We turned and looked back across the snowfield several times to see our tracks. That is one of the wonderful sights a climber sees as he breaks trail in virgin wilderness. I have never ceased to thrill at seeing my tracks after crossing a virgin snow slope. The slope was not that difficult, but it did make one think of the dangers of crossing that slope. We worked up to the summit and enjoyed something to eat.

Thompson Peak. Lyman Dye Photo

I think there are about 3 terraces in that basin and it only took us about 30 minutes to glissade down from the saddle to Fishhook Creek. We would go zipping down the steep section then run across the flat and take on the next steep section. We had to stop and rest our legs several times because we were not used to that kind of exercise. What a wonderful day!

We generally would take the Marshall Lake Trail up the ridge to the north of Thompson Peak and then contour out across the upper basin to the headwall, when we took people on a one-day climb of the peak. We used this approach into the upper valley the same as when we would take a multi-day expedition in. I took my Explorer Group in once to climb Thompson Peak and, when we got above the headwall, I decided we should try to climb the prominent crack on the West Face. I figured it would be better than the slog up the West Slope on scree and talus. I felt it was moderate enough that the boys could handle it. I later took parties up this same route because it gave them more of a challenge and a true climbing experience.

I think it was the second pitch up this crack that one of the boys kicked a rock loose and it fell down among the group. I asked one of the boys to check the belay rope to see if the rock had hit or cut it. I was told that it was okay. When the first climber got to me, I checked the rope between him and the next climber where I thought the rock might have hit. The rope was cut about halfway through the diameter at that point. I took out my knife and immediately cut the upper 70 feet out of the length. When I got the group up to me, I had a serious talk with all of them about rope safety and the need to check things as the rope passed through your hands while on belay and coiling.

Mount Regan

We went in several times to climb Mount Regan. The first time, we went up the West Ridge from the lake outlet. We got up to a notch in the West Ridge and had the impression we could jump across the gap. It looked like it was a pain to down-climb and then come back up the other side. I can’t remember how long we stood there and debated whether we could make that jump. I decided we better not try it so I down-climbed and came back up the other side of the notch. I was glad when I had gotten down below and looked at how big a gap that was, that neither of us had thought it wise to jump it. I don’t think it could have been done. We were standing on the ridge up above later when we heard this screech and felt the pressure from an eagle flying over us. The “whomp, whomp” of the wings was something to behold. The concussion was something I had never felt before. We made the ascent and returned down the snowfield on the north side of the peak. Another time we went back later in the Summer and climbed up the North Couloir Crack to the summit.

Mount Regan. Lyman Dye Photo

Carol, the kids and I went in on a family outing one time, camped at the lake and had a good time. One time, we camped there and the weather turned bad just after we got there. We ate our supper with the rain pouring down and us sitting in the doors of our tents.

One 7-day expedition, I had a fellow from Denver as part of the group. The first evening into the expedition, a storm front moved in to the east of us and he asked me about lightning storms in Idaho. He said that the Colorado storms were something to behold. The second night there was a storm front out on the West Side of us. We were to camp the 3rd night at the lakes below Baron Pass and as we came across the pass to the north of the basin, I saw the cloud formations building up in the southwest. We got to the camping spot and had finished our supper when I noticed the thunderhead over towards Packrat.

I told the group to button down their tents and get prepared for an Idaho lightning storm. We were, of course, camped in a small cirque below the pass with ridges all around us, so I felt that they were going to get a real show. In about 10 minutes, it commenced and, for the next hour, there was hardly a blank quiet moment in the display. The lightning flashed. The thunder claps came and resounded off the ridges above us, rattled their senses and left the ground shuddering under their feet. When the storm passed, the fellow from Denver conceded he had never in his life witnessed such a display. I was thrilled that nature had come across with such a witness of Idaho nature.

Teaching Survival Skills

I took a group of girls from Blackfoot one time on their Laurel High Adventure Outing. We hiked up the Redfish Lake Trail to our camping spot below Baron Pass. We did a little scrambling around on some of the rock formations and talked about survival, orienteering and wilderness survival. The final day of our outing, we headed out over the pass in the Stephens Lakes area and then back down Fishhook Creek to Redfish Lake. When we got to the pass, I told the girls I was going to leave them to work their way down to the lakes. We went over what we had discussed about cross-country travel in the mountains and that this was a test of their ability to apply what they had been taught. I knew that I could beat them down there with ease.

I was surprised when I got to the lake to find a group of boys from the Northwest Outward Bound Program just coming off solo survival. They were a pretty dirty-looking bunch. I told them in about 15 minutes, there were going to be about 20 girls coming out of the timber and they might want to put on their best behavior when they showed up. I believe they thought I was pulling their leg. There were some of them that decided to clean up a bit just in case. I am not sure who was the most surprised–the boys or the girls–about that chance meeting out in the wilderness. The girls and their leaders handled it very well. I had not planned that meeting but it was an interesting experience. We hiked on down through the timber and underbrush and, on occasion, I took the time to stop and point out to them things to look for so that they would arrive where they wanted to. Fishhook is not the easiest drainage to travel in and find your way, but we made it in good shape. We found the trailhead, fresh water and lots of laughing and giggling along the way.

Horstman Peak and Adventures with Wildlife

I took my son Gregory in on a little climbing trip once up Fishhook Creek and up between Mount Heyburn and Horstman Peak. When we crossed the creek, there was a big decaying tree there we walked along. When Greg stepped down, he dislodged part of the log and out came a group of bees. They were hopping mad and got him with a sting or two before we got away from them.

We went on and climbed Horstman Peak then moved on up on the flank of the Monolith, Braxon and Splinter Tooth. Greg did not want to have anything to do with the Splinter Tooth. There was a fire over in the Payette Forest at the time, so the Sawtooth area was pretty smoky and we didn’t get any good pictures during our trip. We spent the last night camped above the Aiguille’s in the upper basin. One Spring, several of us went in on a little overnight trip up Redfish Creek to see what the snow conditions were like. We camped just above the switchbacks, below Alpine Lake. The trail was pretty much covered above the Garden of the Gods.

We spent the night on the snow and, after breakfast the next morning, were on our way back and found fresh blood signs on the trail. We had not seen it going in the day before and decided to keep our eyes open. We came on more tracks and bloody areas as we descended. We came to the conclusion that two Lynx cats had jumped a doe and been chasing her. The Lynx seemed to change places with each other one on a high track and one on a lower one. We figured they would chase her and then jump down land on her back or flank until she fought them off.

We could see where one or the other of the cats would knock her down and there would be a bloody messy spot on the trail. We finally found where they had worn her down and killed her just above the Garden of the Gods. We apparently were not that far behind them because we found her carcass and some distance away her head partially eaten. You could see the claw marks on her back and rump where they had attacked her coming down the trail. That was the first and only time that I had been that close to a kill in the wilderness. I have found decayed bodies and hides from death or killing in the woods before, but never had I been that close to the actual event.

I was out on a morning climb above Iron Creek one morning keeping in shape and came upon a mountain goat and two kids laying in a pocket about 20 feet from where I was climbing up the ridge. The mother arose and came within about 15 feet of me and stood and looked. I, of course, stopped and watched her as well. I wished I had brought my camera but didn’t think I was going far nor would see anything of interest. I tried after that to take my camera whenever I was in the mountains. I was surprised that she let me get that close to her and the kids. Normally they scoot as soon as they hear sound.