I hiked the Inca Trail in February 1977. The article below was originally written in 1977. In celebration of the hike’s anniversary, I rewrote the article updating it a bit. Enjoy.

“Senor, llegaremos pronto a kilometro 88.”

“Gracias,” thanking the conductor, I said goodbye to the 2 Germans sitting next to me, grabbed my backpack and worked my way down the narrow aisle toward the door. The train lurched to a stop and I soon found myself standing alone next to the track as the train crept away. After weeks of traveling, preparation and a fair amount of hassles, I was at the beginning of the hike that I had dreamed about for 2 years: El Camino Inca, Peru’s now-famous Inca Trail to Machu Picchu. The scene from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid where Butch, the Kid and Etta are standing in the ruins of a train station in Bolivia, quickly flashed through my head. I briefly sympathized with all 3 characters. The Kid know ing the idea of coming to South America was idiotic; Etta, tied to her destiny for better or worse; and Butch, ever the optimist, trying to put a positive spin on the decision to travel to Bolivia.

ing the idea of coming to South America was idiotic; Etta, tied to her destiny for better or worse; and Butch, ever the optimist, trying to put a positive spin on the decision to travel to Bolivia.

A light drizzle and the roar of the Urubamba River behind me brought me back to the present. It was 1977 and the Inca Trail was not the popular tourist destination that it is today. In fact, there were no Adventure Travel companies or local guides leading hikers across the trail. I would soon find out the trail was going to be a wilderness experience on steroids. Although the long gone Incas were the last people to inhabit the high terrain along the route, their spirit lived on in the ruins and souls of the Andean Indians.

I spotted the narrow suspension bridge crossing the churning Urubamba. The shaky bridge was of recent construction but was built on foundations constructed by the Incas more than 500 years earlier. The time for reflection was over. It was dusk. It was starting to rain harder. I needed to find a campsite. I found my parka, put on my pack and crossed the swaying bridge. On the other side of the river, the trail turned up stream and worked its way through a Eucalyptus forest. As I walked, in addition to feeling that I had bit off a little too much, a lot of thoughts crossed my mind. Up until this point, my journey had been somewhat tame. Reality was now staring me down and inexorably drawing me along.

I suspect that it is a lot easier to travel in South America in 2016. In 1977, my trip took me to Miami, Quito (Ecuador), Lima (Peru) and then Cuzco, the center of the defunct Inca Empire. Flights were usually behind schedule and airports were filled with crowds of jet-lagged passengers, noisy taxi drivers, sneaky pickpockets and aggressive vendors. Couple these elements with the inevitable late-night arrivals, traveling in South America was both challenging and exhilarating. Had the adventures and hassles along the way prepared me for this hike?

Following the trail, I soon came to the Llactapata ruins at the mouth of the Cusichaca River at an elevation of 7,500 feet. I made camp, fired up my kerosene stove and started to cook. It was dark, cool and damp. The sound of the stove was reassuring. Pulling off my pants, I discovered that both of my shins were scraped raw. I was at first puzzled. Why had I not noticed these injuries earlier?

Traveling the rails . . .

Five hours earlier, I was standing in Cuzco’s San Pedro train station for the Cuzco-Santa Ana railroad line. There was a tourist train to Machu Picchu but it did not make stops, so the previous day I bought a first-class ticket on the local train. The next day I arrived at the station early. There was no train in the station but plenty of passengers of every size and description, many carrying chickens, one carrying a side of beef, one was leading a goat and many had baskets full of the bounty of local markets. This mass of humanity was a colorful composite of the regions native inhabitants.

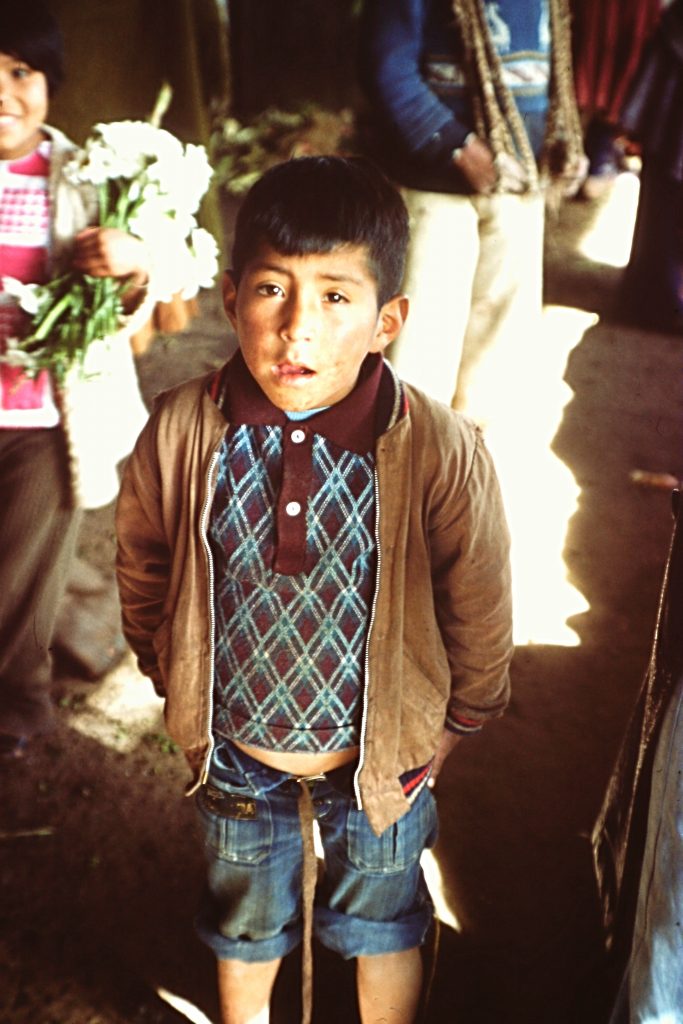

The inhabitants of the Andes highlands at a market near the train station. Many of these people were doing last-minute shopping before boarding the train.

As I waited, a small boy came up to me and asked me the time. I checked my watch and told him. He thanked me and then warned me to be careful with my camera, watch, wallet and pack. “Hay muchos ladrones aqui,” he said. “There are many thieves here.” Well, as you might expect, with the unfounded wisdom of a 25-year-old Gringo, I thanked him, told him the whole world was filled with thieves and I was not worried. He shrugged his shoulders, shook his head and walked away quite disdainful of my response. Soon thereafter, the train backed into the station.

This is the boy who warned me about the thieves. Sometimes we are just too smart for our own good.

The people waiting for the train suddenly were on their feet, rushing for the train. Although I had a reserved seat, I was caught up in the frenzied crowd and swept along toward the train. When I reached the coach assigned on my ticket, it seemed the protocol was every person for themselves. The doorway was narrow, I took off my overloaded backpack, held it tightly to my chest with my left hand, put my right hand over my wallet in my right front pant pocket and stepped up onto the first step. At the same time, 2 Peruvians were shoving and crowding me as they joined me on the first step leading to the vestibule. I looked at the one on my right. He smiled and raised his eyebrows, which I naively interpreted to mean, “Isn’t this a crazy way to run a railroad.” I climbed the next 2 steps into the vestibule with my antagonist still pushing me along. I turned to enter into the coach’s seating area and was relieved to see my assigned seat in the first row on my left.

I quickly pulled the hand covering my wallet out of my pocket to use both arms to place my pack on the baggage shelf over the seat. This maneuver was accomplished quickly and flawlessly. So were the moves of one of my 2 antagonists. In a flash I felt my wallet leaving my pocket. I looked down at the small man at my side. I must say he had a Divine look of innocence and detachment on his face. I was momentarily at a loss as what I should do. I had foolishly left more than $100 in the wallet (a fortune for me at that time), my driver’s license and other keepsakes. I told him to return my wallet. He said, “No entiendo.” I looked behind me for his accomplice, he was gone. I opened the window and yelled for the police. How stupid was that? There were no police at the station and how would I prove who took the wallet?

Standing by and guarding my backpack, I was mentally ready to chalk up my loss as a valuable lesson learned. My antagonist was slowly working his way down the aisle filled with Peruvians with their chickens, canvas bags, baskets and old suitcases. When he was half way down the aisle, he looked back at me and smiled, as if to say that “I was as dumb as a tourist could be.” The smile! That damn smile? Something snapped in me. I asked the young woman in the seat next to me if she would watch my backpack which was way more valuable than my wallet. She agreed. I started down the aisle. It was still clogged with people and I couldn’t make any progress. Seeing this, the thief smiled again. In a fit of genius or insanity, I climbed up on the back of the low bench seats, using their tops as stepping stones to bypass the crowd in the aisle. He saw me coming. The smile vanished from his face, turning, he knocked a women out of his way and picked up speed. He reached the far vestibule and turned left and exited the car.

I was hot on his trail. I jumped down to the platform. I looked right. Nothing. I looked left. Nothing. As I swung my head back to the right, my peripheral vision caught movement. He was climbing between the 2 coaches. I jumped for him and grabbed his foot but he pulled it from my hand and continued his escape between the coaches, dropping down on the opposite side of the train. I climbed through the vestibule, knocking somebody out of my way and jumped down on the opposite side of the train. The thief in his haste had fallen down in a crowd of people. He stood up and started to run but did not get far. I tackled him, grabbed him by the lapels and shook him yelling “Va a morrir.” “You are going to die.” Suddenly, my wallet landed on the ground next to me. I had one of those “Oh Shit” moments as I had a vision of myself in the Cuzco jail for assault. I stood up. The thief scurried away and I suddenly felt like maybe I should have let the thieves have the wallet. Everyone was staring at me. I looked around. No police.

I gathered my wits and climbed back into the train coach. Inside, everyone was looking at me. I thought “Man, I am the ugly American.” I held up the wallet and said to no one in particular, “Tengo my wallet, I have my billitera” mixing English and Spanish. To my surprise the people clapped, several smiling slapped me on the back, one shook my hand and smiled. Back at my seat, the young woman was diligently guarding my pack. Emotionally wound up, I collapsed in my seat. A couple of minutes later, 2 Germans came into the coach and asked what caused all the excitement on the platform.

Now (5 hours later) I was alone, listening to the rain spatter on the tent at the start of my great adventure. Clearly, I had ripped up my shins when I tried to grab the thief when he was climbing between the cars. Suddenly, I was missing the train which at this point seemed like a safe, comfortable refuge with a destination certain. What next, vipers, banditos, panthers? The trip was already turning into an emotional roller coaster.

How the seed germinated . . .

Enthralled with the history of South America, I was committed to visiting the continent between seasonal jobs with the National Park Service. I learned about the existence of the Inca Trail from reading The Lost City of the Incas: the Story of Machu Picchu by Hiram Bingham, the man credited with discovering Machu Picchu. The idea of hiking the trail began to sprout. However, other than general information confirming the trail existed and that it might be passable, I could find few details that would aid me in planning the trip. I knew my visit would be during the rainy season. I had lived in Costa Rica during a rainy season and so I had some idea of what the term “rainy season” meant. I remember thinking of Ben Franklin’s quote, “Nothing ventured, nothing gained” and packed accordingly.

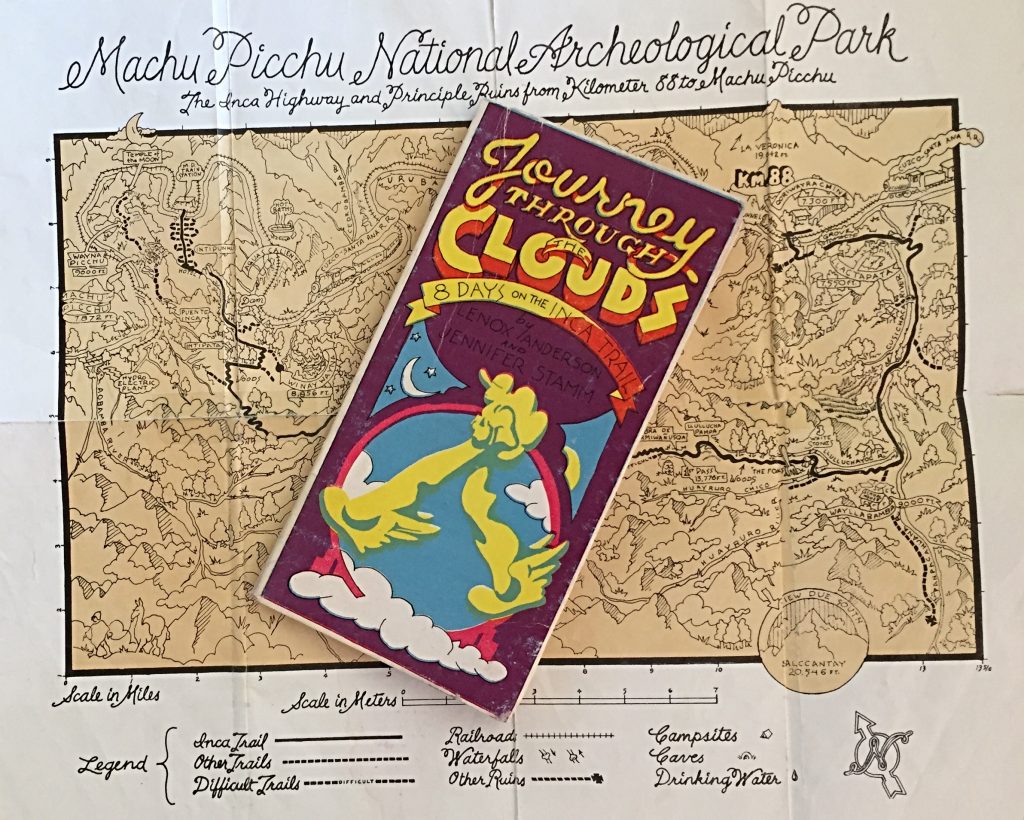

I left for South America in early January, first visiting Ecuador and then traveling to Peru. Arriving in Peru, I still was not sure that hiking the Inca Trail was feasible. In a tourist office, I managed to secure a copy of hand-drawn map showing the trail. Then, while hanging around in Lima, I stumbled into a bookstore and found my version of the Holy Grail, a guidebook entitled Journey Through the Clouds: 8 days on the Inca Trail. The book, which included a professionally hand-drawn map, was published 4 years earlier by Lenox Anderson and Jennifer Stamm. The first paragraph was encouraging:

“The following guide has been produced with the hope that well-prepared hikers will be more able to enjoy the magnificent mountain scenery and intriguing ruins between Kilometer 88 and Machu Picchu and will spend less time and energy looking for the not always clear Inca Trail and drying out drenched gear.”

Finding the book and the included map was like finding gold. I was not crazy after all. The Inca Trail was passable. I boarded a jet and flew to Cuzco.

My discovery of the 1974 Journey Through the Clouds and the accompanying map were the key to my successful trek.

Not so fast . . .

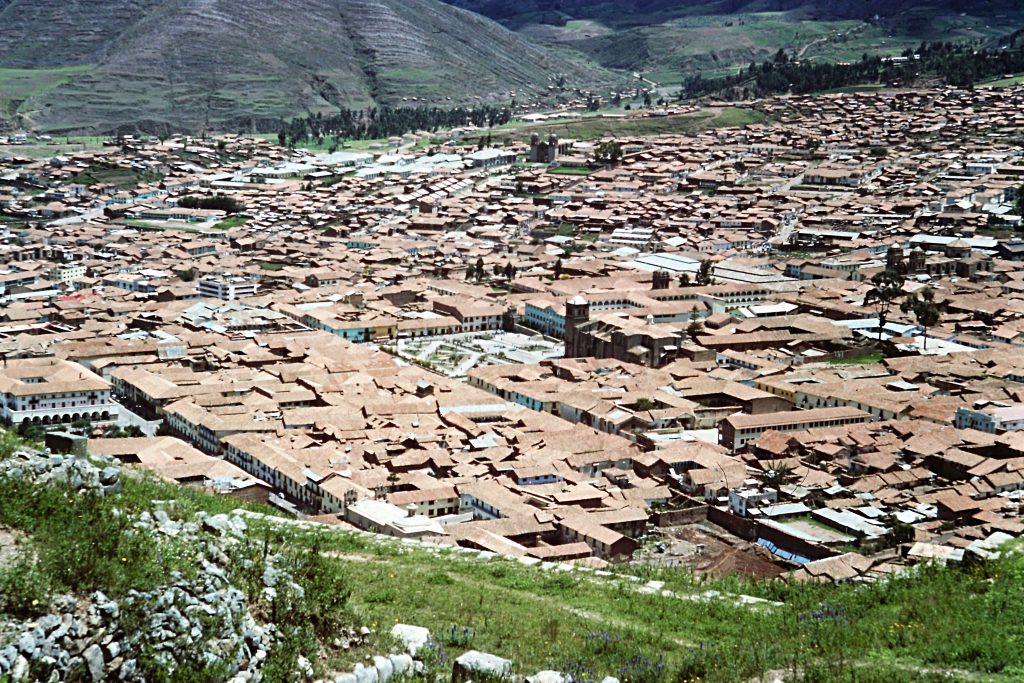

Upon arriving in Cuzco, I found that the elevation (over 11,000 feet) was going to be a problem. I felt wasted after walking a couple of blocks. My salvation was that I had lots of time to acclimatize. The first hotel I stayed at had about 8 rooms and a friendly owner who noticed and quickly diagnosed my malaise and prescribed a cure. He gave me a cup of tea made from Coco leaves. The same leaves that are processed into cocaine. The same leaves that the Indians chew. The leaves, the tea, Mate de Coco, was legal and readily available. Being almost a virgin when it came to stimulants, I was astounded at the effect of the tea. I was a new man. I went out for a walk and found a group of Peruvians playing basketball outside a nearby school. I managed to convince them to let me join in the game. After 5 minutes, I realized that the Mate de Coco was no substitute for acclimatizing.

Cuzco in 1977. The former Inca capital sits At 11,150 feet and is surrounded by the Andes.

After a couple of days in Cuzco I was fortunate to learn that a woman, Senora Flores, rented rooms in her home. Her house was located on the Plaza de Armas in a massive stone and mortar building. The living area was located on the upper floor of the building and was centered around a beautiful courtyard. Two days later I moved into Senora Flores’ home and settled into the Cuzco life. While other roomers came and went on an almost daily basis, I made this my base camp and Senora Flores came to call me her “ortro hijo.” Her real son (a doctor) seemed unconcerned by my sudden inclusion in the family. From this welcoming world, I was able to explore the surrounding highlands and to travel to Bolivia. More importantly, it gave me a home base to prepare for my Inca Trail adventure. While many of the Peruvians I met knew of the Inca Trail, none had followed its path. Nevertheless, they almost uniformly warned me against hiking it during the rainy season and, of course, February was the middle of the rainy season. The guidebook’s weather section was concise and less than encouraging:

“The weather in these high mountains changes abruptly, and storms are likely at any time of year. In the rainy season, October to March, the unstable conditions are even more severe. Cold rain, thunderstorms and hail are frequent, and snowstorms occur occasionally. Rising valley fog and low clouds are constantly coming and going often obscuring views and making orientation difficult. . . . Darkness falls quickly in the steep canyons, so allow yourself plenty of time for finding and setting up camp.”

Some days it rained so hard in Cuzco that one avenue resembled a creek in flood stage. The warnings and my observations caused me a bit of anxiety which was heightened by my inability to find a hiking partner.

Who were they . . . and where did they go?

The Inca Trail has an interesting but tragic history. When the Spanish arrived in Peru in the early 1500s, Cuzco was the capital of an Inca Empire that stretched from present day Central Chile north to Columbia. The Incas, much like the Romans, ruled over a disparate group of cultures that they had subjugated. The Incas had divided their empire into 4 administrative zones and Cuzco sat in the center. Like almost all indigenous populations of the Western hemisphere, the Incas had a complex and orderly society. The empire was tied together by a road system estimated to encompass 40,000 miles. Many of these roads are now the routes of modern highways and railroads. Many of the remaining sections of these Inca routes still survive in varying states of repair. The Inca Trail which was at the heart of my itinerary was and is the most famous section of the Inca road system.

The Spanish employed the familiar and deadly European colonial strategy of divide and conquer, coupled with a healthy dose of genocide to overcome the Incas. The empire essentially fell apart when the Spanish captured Cuzco. The surviving Incas retreated into remote areas of the Cordillera de Vilcamboma and the headwaters of the Urubamba River. The survivors waged a guerrilla campaign from their mountain hideaways until 1572 when the Spanish captured the last Inca leader Tupac Amaru. He was executed in Plaza de Armas soon thereafter. With their leader dead, their subjects dead or under Spanish control, the Incas disappeared as a society. Remnants of the Inca culture can be found everywhere in the highlands around Cuzco from the many ruins (some of which were converted into Spanish buildings) to the culture of the surviving indigenous population that inhabit the mountains and towns.

Time to hit the not-so-dusty trail . . .

While acclimatizing, I started to accumulate food for the trip. Nothing light was available other than dried soups. I would have to live on the soups, cans of tuna and a healthy supply of Mate de Coco. By the time I was acclimatized to the elevation, I had ample time to read the guidebook 100 times. It was a godsend for strengthening a solo hiker’s confidence but it also presented a cautionary tale.

“The Inca road varies from dirt paths worn by local compasinos to a wide, level stone trail. In some places, all traces of the Inca trail have been obliterated; in others, the white granite blocks lie scattered in the bunch grass. The trail climbs steeply, particularly over the first and second passes and is rocky and uneven over these sections. In the more level portions of the trail, between Sayajmarca and Phuyupatamarca, the trail is a quagmire during the rainy season. In some places, the trail is narrow and drops off precipitously.”

Now that I was a mile into the hike, dry in my tent, these cautionary words were forgotten for the moment.

. . . lost but then I was found . . .

The entire length of the Inca Trail was already designated as a National Archaeological Park albeit with no government management of the trail or its ruins outside of Machu Picchu. From Bingham’s book and the guidebook, I knew that remnants of Inca civilization were strung out along the trail. The first of these ruins was at my campsite, Llactapata. Arriving in near darkness, I could not see anything. When morning dawned, I found the ruins to be impressive. The most prominent feature of Llactapata are the terraces which start on a bluff above the river and rise up more than 100 feet above the trail. Although the terraces were no longer used, they demonstrated that before the Spanish destroyed the culture, this village was large and agriculturally important. The remains of the houses are located in the upper sections of the terraces. The Incas used thatched roofs and, although they were gone, I remember marveling at how similar the construction of the Llactapata walls were to the construction of the homes that many Peruvian compesinos lived in 1977.

After exploring the ruins, I broke camp and dropped down to cross the Cusichaca River which was flowing into the Urubamba below the ruins. The rickety bridge was constructed of logs and mud. The trail skirted around a gorge by climbing up an open slope to a hill top that gave me a good view into the valley ahead. This valley was under cultivation and I knew from the guidebook the trail would wander 5 miles through the valley to the village of Wayllbamba. The trail is routed roughly 500 feet above the Cusichaca for the first 3 miles. To the north, I had a great view of glaciated Mount Veronica (19,367 feet). The small farms that I passed were primitive. Growing corn and potatoes, 2 staples in the Andes, appeared to be the primary occupation of these farmers. I met several of the inhabitants along the trail and every one of them had time to pass a word or two. Several wondered why I had such a heavy pack, likening me to a horse. “Como un caballo,” was a common theme. None of them warned me about hiking the trail alone in the rainy season which was a welcome relief.

The first bridge over the Cusichaca River. This was the first of 2 bridges maintained by the valley’s farmers. Crossing the Cusichaca would have presented problems without the bridges as the water was running fast and furious.

Looking up the Cusichaca Valley toward the village of Wayllbamba.

Looking back down canyon toward my starting point along the Urubamba River.

The 2nd bridge across the Cusichaca River. My trusty Trailwise backpack is on the left. Trailwise equipment was made in Berkeley, California and was endorsed by the Complete Walker, Colin Fletcher.

After passing several small farms, I walked through a cluster of buildings that I later learned was Wayllbamba, the point where the trail left the Cusichaca River to climb into the high country. However, the trail along the river was much easier than I had expected and the village much smaller than I envisioned so I kept hiking up the canyon believing that Wayllbamba was up ahead. I had not walked far when I heard a racket behind me. Looking around, I found 5 people chasing after me. They quickly caught me and wanted to know where I thought I was going. I told them Machu Picchu and they laughed, shook their heads and pointed back to what I now learned was Wayllabamba. One of them insisted on carrying my pack. The pack dwarfed him but he put it on his back and they marched me back to the village, talking and laughing the whole way. In the village, we shared some candy while trying to communicate. Party over, they took me to a bridge across the river and pointed me toward the trail. I gave them several of the cans of tuna fish I was carrying as a thank you. I started up the trail toward the first pass which was 6 miles and 4,700 feet above me. The last thing I heard from the villagers was “Cuidado con el torro.”

The village of Wayllbamba did not register as the landmark I was looking for and I walked right past it.

A good trail climbed up the narrow side canyon toward the first pass on the route, El Abra de Warmiwanusqa. The day was sunny to this point but as soon as I entered into a lush forest, the clouds rolled in and a hard rain started to fall. The trees protected me from the deluge but the trail was soon a stream in places. After gaining roughly 2,500 feet, I reached a small meadow and the rain had stopped. I decided to set up camp before the heavy, dark clouds started to unload again. I cooked dinner watching the fog and darkness close in.

Mount Veronica as viewed from Wayllbamba. This impressive 19,342-foot peak dominates the skyline.

No bullshit . . .

My 3rd day on the trail dawned foggy and wet but the sun soon broke through the clouds. I packed up my damp belongings and started up the trail, hoping to get over the 13,799-foot pass (Warmi Wanusqa) before it rained again. Warmi Wanusqa means “Dead Women” in Queecha, the primary language of the Andean Indians. It is the highest elevation on the trail and is over 7,000 feet higher than my starting point at Kilometer 88.

I quickly climbed out of the forest, gaining altitude and swiftly powered by my never-ending supply of canned tuna and Mate de Coco. I arrived in a big meadow, which gave me my first view of the pass. More immediate was a view of a large black bull adorned with threatening horns. The words “Cuidado con el torro” now made sense. The pass looked a long way off. The bull looked very close. There were no fences. For the present, the bull ignored me although he was standing directly on the trail about 100 yards ahead of me. The villagers’ warning made me a bit nervous but I was ready for a break. I dropped my pack and started to change film. The bull continued to show indifference.

The neighborhood bully: Cuidado con el toro.

Sitting on a rock, I put on a telephoto lens and started to shoot photos of the pass. At the 3rd click of my shutter, the bull snorted loudly, shook his head and started charging towards me, its hooves throwing up mud and water. The next “Oh Shit” moment was upon me. Visions of the bull run at Pamplona raced through my head. Not being Ernest Hemingway, I grabbed my pack and started running up the hillside, running until I was out of breath. I looked down the hillside and the bull had stopped at the spot where I was sitting moments before, rubbing its horns on the rock. Relieved by my perceived escape, I crossed the side slope heading toward the trail at the upper end of the meadow as quietly as possible. Once back on the trail, I resumed my climb toward the pass. After many rest stops, I arrived at the high, barren pass.

The Bull’s Meadow safely behind me.

Warmi Wanusqa Pass at 13,776 feet looming ahead. The trail is on the left zig-zagging up the slope.

Looking down the line of my ascent to Dead Woman Pass toward Wayllbamba and the Cusichaca River.

The trail approaching Warmi Wanusqa Pass.

The sky was clear and the view was breathtaking, not that I had much breath left to spare. High mountains and steep canyons stretched far into the distance. A trail was visible descending from the pass down to the Pacamayo River and then climbing up to the next pass, El Abra de Runkaraqay. I spotted the next group of ruins (Runkaraqay) sitting below the pass. The 15-16,000-foot peaks rising up above the pass were enticing but I was not yet the peakbagger I was destined to become and did not consider climbing them. Now, optimistically, I thought my adventure was going to be successful. It is amazing how good trails ahead, clear skies above and Mate de Coco in your pack can make you feel. I had the Andes by the tail.

This pass, not on my route, is also crossed by a trail. There is a lot of country to explore off the main trail.

Resting on the pass, I thought about the people who had crossed this pass before me. No doubt people were crossing Dead Woman Pass long before the Incas conquered the region. The genocidal Spanish no doubt crossed the pass. Hiram Bingham had crossed the pass. Locals, acclimatized to these high elevations, were still using the pass. Here I was sitting on top of the world, in some ways as out of place as a swimmer in a desert wondering what brought me to this spot. Sometimes our relevance in the world is a mystery.

Clouds coming and going highlighted the entire hike.

The 2,000-foot decent to the Pacamayo River was quick and uneventful. The trail was not “Cadillac” but there was a good tread and I could see it far ahead of me. The walk down the trail from the alpine heights to jungle below continued to stoke my elation. At the river, I dipped into my supply of tuna for lunch and then resumed my hike, climbing toward the 2nd pass. The steepening trail led up to the Runkuraqay ruins at 12,464 feet. Having plenty of tuna and dried soup left in my pack and the sun shining, I decided to set up camp at the ruins rather than pressing on to the 2nd pass which was another 2 miles and 1,300 feet above me.

Water, water, water everywhere.

Runkuraqay consists of 2 buildings, one small and oblong and one large and round. Neither was in good shape. Archaeologists were debating the purpose of the 2 buildings. They were located on a knob sitting in the middle of the canyon which indicated to me that the Incas who built the structures enjoyed a good view. Looking back, I should have expected that this spot could get a lot of rain by the condition of the ground around the ruins. It was saturated and it took me some time to find a spot dry enough to pitch my tent. But it was sunny and I had dry rock walls to spread out my wet equipment. With the sun out, this spot was as delightful and welcoming as any place I have ever camped. The views were almost as good as those on Warmi Wanusqa.

My camp at Runkuraqay. This spot was well drained because the slope just past my tent dropped straight down several hundred feet.

The upper ruin at Runkuraqay showing the overgrown conditions.

Call me Ishmael . . .

The rains started again sometime during the night. I was vaguely aware of rain beating on the tent but not fully aware of how much rain was falling until morning after a cup of tea. Well, no rush, I thought. I will just wait until the rain lets up before moving on. The rain never stopped that day; only the intensity changed from time to time. Wind, hail and thunder made guest appearances throughout the day. Day 4 became a rest day.

Reading and my amazement at watching the rain come down and the clouds come and go occupied my time. Forgive me for digressing but finding myself alone in a tent in the Andes on a day under a constant deluge was an enlightening experience. I had picked up an annotated copy of Moby Dick in Lima. I was now physically in a sea of mountains and mentally out at sea on the Pequot. The book is perhaps the greatest American novel but so convoluted and dense that I had not admired it until reading the annotated version. The book’s complexities require a guide so a person can perceive the book’s many themes. Moby Dick is about so many things but in its first paragraph it captures Ishmael’s motivation for going to sea and just maybe my motivation for hiking the Inca Trail in 1977:

“Call me Ishmael. Some years ago – never mind how long precisely – having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way I have of driving off the spleen and regulating the circulation. Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off-then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. This is my substitute for pistol and ball. With a philosophical flourish, Cato throws himself upon his sword; I quietly take to the ship.”

And then again, maybe not. Reading that night, I came across Ishmael’s comment about the name of a Polynesian island, “It is not down in any map; true places never are.” I am still mulling over that statement 40 years later.

Morning on the 4th day.

Who is in charge of this place . . .

I awoke early the next morning. The clouds had lifted a bit and fresh snow frosted the higher peaks. Slowly a desire to hike the remaining 15 miles to Machu Picchu and get out of the rain-soaked mountains took over my better judgment. On paper, this feat looked doable. After the trail crossed El Abra de Runkaraqay, just 2 miles ahead, the route was for the most part downhill all the way to Machu Picchu, descending from just over 13,000 feet to just under 8,000 feet. At least that is what the route looked like on paper. Easy, I thought.

Fresh snow above 14,000 feet.

One of two small lakes below Runkaraqay Pass.

Runkaraqay Pass (13,122 feet) with a skiff of snow.

The vegetation varied widely over the route this stunted growth was near the borderline of the treeline and the jungle.

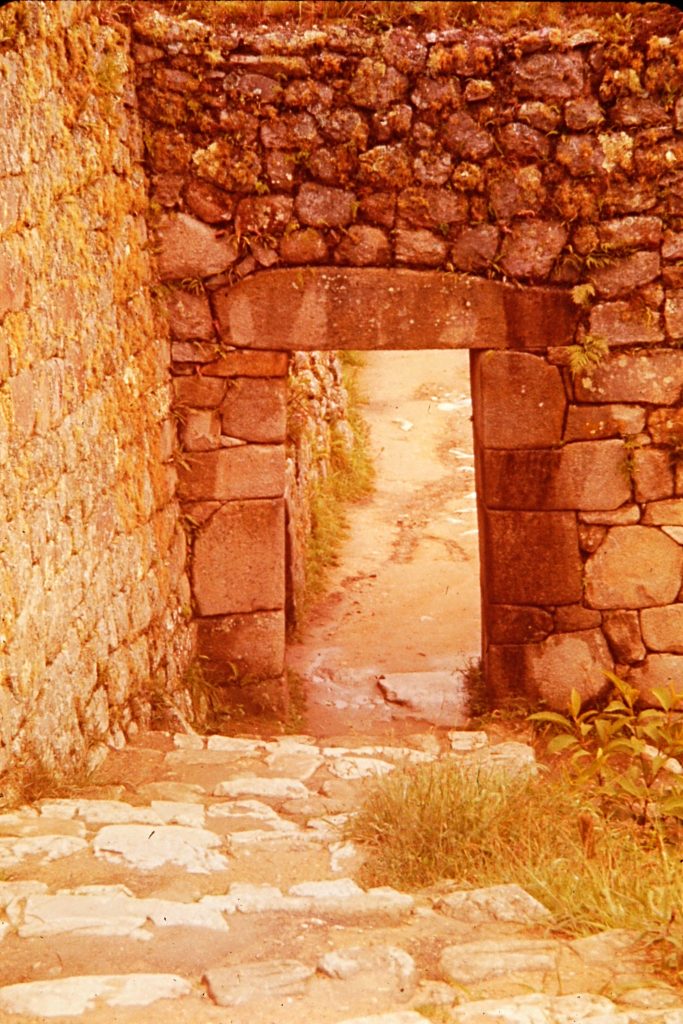

Plans made with resolve strong, I broke camp. I was up and over the cold, damp 2nd pass in no time. A light drizzle and fog cut the view to almost nothing. Dropping down off the pass, I reached treeline where the trail became a bog. Thick mud and deep water was often higher than my boots. The boggy trail reinforced my resolve to reach Machu Picchu and a warm shower. I soon rounded a corner and caught a fleeting glimpse of the ruins of Sayajmarca sitting on a ridge above me. The ruins disappeared into the mist but I quickly found a stairway cut into the stone which led to the ruins. I climbed up the steps and found myself in the most impressively located archaeological site I had yet visited. The ruins are located on a narrow ridge with only the treacherous, moss-covered stairway as access. The ancient city was built on 3 different levels. The ruins include many walls with geometrically-spaced windows. There are also remains of an aqueduct system complete with the remains of fountains. The location would have provided the inhabitant with 360-degree views and an easily-defensible perimeter.

The slippery stairway leading up to Sayajmarca.

Nearing the top of the steps.

Sayajmarca

Grinding implements found in Sayajmarca.

After exploring the ruins, I pressed on. The bad trail conditions continued to deteriorate. In many places, the muddy stretches of trail gave way to narrow, rocky sections that traversed across cliff faces with sheer drops. The Incas (or their slaves) had carved these sections out of granite. The forest grew thicker. In many places, it resembled a jungle. Bamboo, giant ferns and other trees crowded the trail’s tread. After leaving Sayajmarca, the trail began a long parallel traverse of the ridge switching from one side of the ridge to the other, undulating up and down, in its long descent to the more tropical environs of Machu Picchu.

The rain was now falling in steady sheets. The sound of the rain was accompanied by the sloshing of my saturated boots. I was wet inside and out. By noon, I arrived at the Inca Tunnel. The tunnel was constructed to bypass a steep granite cliff. It is about 60 feet long, carved through solid granite. Inside there are carved steps, a stone bench and a window. Incas, no doubt smarter than me, used the dry bench to wait out the rain. However, at this point, I could only think of a warm shower and something other than tuna for dinner. I pressed on. Soon after leaving the tunnel, I crossed a 3rd pass which is really a gap in the ridge. The elevation at this point was still over 12,000 feet. Crossing through the gap, I spotted the Urubamba River 5,000 feet below me.

The Urubamba River is 5,000 feet below me. It empties into the Amazon River.

Proceed at your own risk . . .

Continuing down the ridge, I arrived at the point where I could see the next set of ruins (Phuyupatamarca) through the fog. I had descended over 1,000 feet from the last pass to reach these ruins which sit at 11,906 feet. The ruins were 300 feet below and looked close enough to touch. However, the trail appeared to end in a tangle of vegetation. Anxious to reach the ruins (my planned lunch stop), I made the tenderfoot mistake of forging ahead without trying to find the overgrown trail’s tread. In my defense, I quickly found something that looked something like a trail. After losing 200 feet, I realized that this pseudo trail was actually an path of erosion. I had an unobstructed view of the ruins at this point and they looked closer than ever. I estimated the distance at only 200 lateral yards and 100 feet below me. Should I forge ahead? My option was to climb back up the steep slope and look for the actual trail or continue in a straight, albeit descending, direction directly to the ruins. I chose the latter. I chose wrong.

Puyupatamarca as viewed from the point where I lost the trail and decided to descend directly down the hillside.

The steepness of the slope, combined with the muddy soil, quickly turned the runnel into a mud slide. And I slid like I was on a runaway glissade. Thinking back on my descent, I realize that it was only luck that kept me from breaking a leg or worse. Nevertheless, I was at the bottom of the slope, at the base of Puyupatamarca in one piece. I caught my breath and when my heart slowed, I felt elated. Another test passed. Pushing through a bushy hedge, I took one step toward the ruins.

What looked like solid ground gave way. I began to fall. Instinctively I grabbed at the bushes and they stopped my fall. I was chest deep in a hole and only the bushes were keeping me from falling farther. Yes, another “Oh Shit” moment. My first thought was, “What is next?” Chased by displaced Amazonian headhunters? Quicksand? Snakebite? Yes, I thought, “It will be a snakebite.” Looking down to my dangling feet, I discovered that I had stumbled into an Inca irrigation or drainage ditch or maybe it was a defensive moat. Who knows? What I did know was I needed to get out and get out now. The stone walls were 3 feet apart, mostly smooth, covered with moss and the bottom was at least another 15 feet below my dangling feet. The walls were too far apart and too slippery for chimneying. The bush I grabbed was holding but for how long? My heart was racing and adrenaline was coursing through my veins. In my panic, I managed to find a slight purchase for my right boot at about knee height, stuck my foot into it, pushed off and pulled myself out. Laying on my back, I chuckle, relieved at having survived another near-death experience. When my strength returned, I jumped the now obvious ditch and walked into the ruins.

Please sir, some more . . .

Time for comfort food in the ruins: tea, soup and crackers. No, just a couple of cups of Mate de Coco. Based on the events of the last hour I was, on the one hand, more determined than ever to reach Machu Picchu and, on the other hand, thinking I should make camp before some other potential catastrophe over took me. I still had 8 miles to go and I was having one of those epic personal debates about whether to stay or go. Suddenly, a heavy rain squall swept over Phuyupatamarca pelting me with wind-driven rain and then marble-sized hail. The decision was easy after that.

The next 3 miles were easy in comparison to the last 3 miles, though I did have to stop a couple or times do dump water out of my boots and wring out my socks. At this point, the Twentieth Century intervened as I reached the next major landmark on the trail: a series of high-tension, electric power lines that cross the ridge to shorten their route from the Urubamba River to the Aobamba River. Based on the guidebook, I knew that these monuments to civilization did not mean the journey was over.

I opened the guidebook’s map. It showed that the next section of trail was downhill through what the map termed “difficult forest.” Difficult turned out to be an understatement. As I descended, the jungle forest crowded in on the trial. Bushes, trees and vines grabbed at my pack. At times I had to crawl through mud to get under low-hanging downfall. All the while, the tread was only slightly more than an illusion. I began to worry about getting lost or falling into another ditch as well as having a snake drop on my head. I decided to carefully make sure of every step. This slow progress eventually brought me to the bottom of the dense forest and into the open. It was 3:30PM. 4 miles to go.

The next 2 miles passed quickly but then the trail was up to its old tricks. Forested sections had plenty of downfall to block my way. The trail crossed another cliff. This was perhaps the most treacherous spot yet. The Incas had used their stone-working skills to build the route across the face but they had not maintained the route in 500 years and the mossy, overgrown traverse was not very wide. Nevertheless, the crossing went quickly probably due to the tea.

I soon found more Inca construction: wide steps carved in the rock. By this time, the tea had worn off and I was beaten down physically and mentally. Even these steps looked treacherous. Clearly, I thought this walk is on the verge of becoming a death march. Twice I approached what I thought was the Intipata ruins, the gatehouse overlooking Machu Picchu. The first time I climbed a long, steep stairway, only to be disappointed with only a view of the ridge continuing its descent into the clouds. The next time I pulled myself up to the ridge top, I could see the walls of the gatehouse and then Machu Picchu stretching out below me.

Machu Picchu as viewed from Intipata. The ruins sit at an elevation of 7,782 feet in the Amazon Basin.

Photos of the ruins, while impressive, did not do them justice. To my right was the Urubamba River in its deep canyon. The horizon was cluttered with sharp jungle-covered summits. The tourist hotel and the road leading up from the train station were at my feet. The trail swung off to the left, finally dropping down to the ruins a mile away. Funny but, as impressive as the ruins were, I focused on the hotel. I dragged myself into the hotel covered from head to toe with splattered mud. My wool sweater (long before the days of fleece and Gore-tex) was carrying twigs and leaves and my saturated boots and socks sloshed with every step. My luck held. There was a cancellation and I got a room. I cleaned up, found some dry clothes and headed for the ruins. The gate was locked for the night and I thought, “Back in civilization.”

40 years later, the Inca trail has completely changed. You need permits and there are lots of regulations. There are 500 permits issued each day of which 200 are allocated to tourists and 300 to porters, cooks and guides. The trail is now maintained and crowded. Nevertheless, the trail is closed in February because it is deemed too rainy for safe, enjoyable passage. Permits for each year are not available until January but it appears that if you want a guide you should book by the end of November of the preceding year. I think you can interpret this to mean that the only way to be sure of getting a permit is to go with a guide. During 2016, only October, November and December did not sell out.

The following link will provide all the information you need to plan a trip:

http://www.incatrailperu.com/

These two llamas were guarding the ruins when I arrived.

Machu Picchu is noted for its fantastic stonework and remote location.

Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu

Next: Salmon City 1978