“Things that were hard to bear are sweet to remember.“

-Lucius Annaeus Seneca. 4 BC – AD 65

It is true that as time passes we tend to remember the good and forget, downplay or ignore the bad in our past experiences. Nevertheless, I will take the liberty of expanding on Seneca’s premise. Looking back on the Summer of 1975, I still remember both the good and bad of my experiences with equal clarity. In life you simply have to take the good with the bad. The combination of the good and bad creates the whole. The whole is a learning experience that we should not minimize or forget.

In late April 1975 I had returned to Michigan from New Zealand. I was hoping to secure one of the 12 seasonal Backcountry Ranger positions in Sequoia and Kings National Parks. I called the park when I returned and learned that there was no turnover in the Backcountry Ranger ranks. Thus, I knew I would be assigned to the front country again and, worse yet, that it might take me years to secure a backcountry position.

Two weeks later, I was packing to leave for California when I received a phone call from Rocky Mountain National Park. My supervisor in California had given me a strong recommendation and as a result I was offered a job as a Backcountry Ranger. Although I loved the Sierra Nevada Mountains, the backbone of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, I immediately accepted the job. At that time in my life, I believed there could be no better job than a seasonal Backcountry Ranger. Two weeks later, I left Michigan for Colorado for what turned out to be an eventful Summer.

Seasonal Service

Each year the National Park Service relies on season personnel to operate during a park’s busy season. Permanent park staffing is unable to meet the increased demand at peak season. The park service adds seasonal personnel to meet the influx of visitors. Many of the seasonal hires are college students, some are school teachers. Turnover is rare as many seasonal employees come back year after year to work two to three month assignments. Rocky Mountain National Park would be my third seasonal Park Service assignment as I previously worked at Crater Lake National Park in and Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks.

Seasonal employees are public servants who wear uniforms. Seasonals are given training classes at the beginning of the season. They are expected to bring a high level of commitment to their jobs. In theory, they are expected to live up to high ethical standards, to provide polite, efficient service to visitors, protect the park’s resources and represent the National Park Service and it’s long standing traditions. To be an effective seasonal employee you must completely buy into the Park Service’s mission. I had certainly bought in to the culture and hoped to eventually secure a full time position.

Arrival

I arrived at the West Unit offices of the park near Grand Lake, Colorado on May 15th, two weeks before my official starting date. The mountains were still slammed with snow. In early May Grand Lake and the west side of the park were nearly deserted. One of the benefits of being able to start early was the opportunity to spend time in the park before the crowds arrived.

I offered to work as a volunteer for the next two weeks. The offer was enthusiastically accepted. I was assigned to bunk in housing at the Shadow Lake National Recreation Area which is located just south of the park. I shared a house with another early arrival, seasonal ranger, Dick.

A volunteer gig with the Park Service is a sweet deal if you can afford to live on $3 a day and free, often substandard, housing. As a volunteer, I worked six hours a day doing odd jobs for those two weeks. The real work began around the first of June. Since I was the first seasonal Backcountry Ranger to start, I was directed to patrol west side trails till I reached snow line. I provided trail condition reports to Trail Crew Forman (more on the this guy later). Not only was the snow melting slowly but it also snowed once a week for the first three weeks of my tenure. It was clear that the backcountry was not going to open up for a long time.

Dick

Dick was one of those unforgettable characters that I have been fortunate to meet over the years. Physically he resembled an ancient, weathered Richard Boone in appearance. He resembled Boone’s Have Gun Will Travel character, Paladin in temperament. He was a retired Denver high school teacher. He truly was a great person to introduce me to the park, its environs and its denizens. He had worked at the park as a seasonal, operating an entrance station, for 20 plus years.

Dick shared his insights about everything park related as well as his knowledge about how things worked. He described the full time personnel in stark terms which proved to be accurate. He described the seasonal personnel as “half hippy and half fraternity brothers” which also turned out to be accurate. He made it clear that, unlike my other Park Service assignments, the West Unit was riven by factions that detested the other factions.

My best story about Dick took place in late May. I was assigned to road patrol and stopped by the entrance station to deliver a box of maps. While in the station, a Cadillac pulled up. The driver, a rotund gentlemen with a western tie and a cowboy hat and a wife in a mink coat, said, “Howdy Son, I’m from Texas.” Dick responded, “Gee Sir, I’m terribly sorry to hear that!” I should digress that after Coloradans the most common tourist on the west side of the park were Texans. Anyway, this Texan made an exaggerated showing of shock, before letting out a deep belly laugh.

“Son, you had me going there for a minute,” he said. After he drove off, Dick said, “I don’t think he figured I was serious.”

An Overview of the Park

Rocky Mountain National Park is a large park encompassing 415 square miles of the central Rocky Mountains. The Continental Divide forms the park’s backbone. The rivers and streams west of the divide flow to the Pacific Ocean via the Colorado River drainage and, of course, the eastern waters flow toward the Atlantic Ocean via the Platte, Missouri and Mississippi River drainages and the Gulf of Mexico.

The park’s s elevations range from 7,860 to 14,259 feet on Longs Peak. Much of the terrain is high altitude, alpine tundra. Trail Ridge Road reaches 12,183 feet at its highest point, making it America’s highest paved through road. There are sixty or more peaks that climb above 12,000 feet in elevation.

In 1975 the park still had a few glaciers and many permanent snowfields. Rocky Mountain National Park has a cool, wet climate which is classified as a Subarctic climate. The summer of 1975 was cool with lots of precipitation. I learned that local variations of terrain, like slope and elevation were only part of the park’s climate story. The park’s location is a meeting place for cold northern and warm southern air masses. The collision of these air masses can cause all sorts of extreme weather. In the winter Arctic air often collides with warmer, moister air from the Gulf of Mexico causing massive snowfalls. As a result, when I arrived at the park it was still buried in snow. In the summer the collision of the warm air from the plains and wet Gulf air invariably lead to impressive, monsoonal thunderstorms.

The Park Service versus the Wilderness

The use of National Park backcountry areas was increasing so rapidly in the 1970s that managers had to develop management plans to protect the resource. Management plans means regulations. Different parks chose different forms of management. The first step managers utilized was to require backcountry users to secure a wilderness permit. Based, in part, on data from the permit process managers looked for strategies to control use.

Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks chose to regulate and minimize overcrowding by placing daily limits on trailhead entries. Rocky Mountain, chose to control visitors by developing a limited number of backcountry campgrounds. These campgrounds were nothing more than a place to set up a tent. I never saw a designated site that I would have wanted to use as a camp. Most did not have views and their spacing was incongruous with the freedom to explore that brought most hikers to the backcountry. This system was effective in limiting damage to the backcountry because it deterred visitors esthetically and bureaucratically. It was difficult to get one of the limited number of permits. I understood, and still understand, the need for the quota system because there were simply too many people. Weekend days would find bumper to bumper traffic on Trail Ridge Road, trailhead parking lots were overflowing and the trails close to roads were clogged with hikers.

Rocky Mountain Park Service Life

In the 1970s I worked for three different National Parks and one National Monument. Each unit had the prototypical Park Service culture as described above. Each park’s Park Service culture was modified by its own local quirks. The West Unit of Rocky Mountain National Park’s culture was by far the strangest I encountered.

Physically, the park forms a divide between the Mountain West and the Great Plains and between urban and rural societies. As a result of these physical divides, the mix of people who worked at and visited the park covers an immense spread of backgrounds, temperaments and outlooks. Additionally, the park is divided in two for seven to eight months a year when snow closes Trail Ridge Road. The closure leaves the West Unit isolated and on its own. Think of the West Unit as a backwater.

The Park Service is a bureaucracy designed to protect and serve the country’s most important natural resources. Despite its lofty mandate, it is still a bureaucracy with all of the traits of a bureaucracy. The West Unit was a real life example of what I had learned in sociology classes. Like all bureaucracies different parts of the same organization have their own goals and pursue them often at the expense of the organization’s overall mission. Additionally, bureaucrats have a strong preference for maintaining the status-quo. Given the existence and necessity of a bureaucratic hierarchy, there is a tendency to find many employees with low job satisfaction and low morale which results in poor job performance.

There were permanent employees in the West Unit who wanted to advance their careers and those who were satisfied with their lot in life and who desperately wanted to protect the status-quo. The surest way to advance your Park Service career was, of course, to secure promotions. The easiest way to secure a promotion was to apply for a more important job in another park. Thus, the upwardly mobile were always transferring from park to park. This dynamic created two types of employees: the go-getters and stick-in-the-muds. The stick-in-the-muds at best tolerated the go-getters and at worst hated them.

The West Unit had its own manager, Jim Liles. He was clearly a go-getter. He grew up in the National Parks. His dad was a Ranger. Liles was a good natured, tradition based employee who in my opinion embodied all of the good qualities that the Park Service represented. The Administrative Officer for the West Unit was a Native American, originally from Lone Pine, California. She was another go-getter and the most helpful government employee I ever met.

My boss was the West Unit Backcountry Ranger. As I soon discovered, he was disinterested in his job and the backcountry. He was the consummate “hands off” manager. He did not want to supervise. He was not interested in your concerns or ideas. He absolutely did not want to hear about any problems. His best buddy was the Trail Crew Foreman, a retired policeman who never would be found on a trail or far from a six pack. My boss’ worst enemy was the District Ranger who had just transferred to the park, arriving the same week as I. Why did he hate the District Ranger? Simple, because he was a go-getter.

Working under the full time employees were the seasonal employees. The West Unit’s seasonal employees encompassed a wide variety of personalities and backgrounds. Many of the West Unit seasonals, like Dick, had spent many Summers working on the west side of the park. Others, like me, had moved around. So, like the full time employees, there were seasonal stick-in-the muds and seasonal go-getters. As with the full time stick-in-the-mudders, the seasonal stick-in-the-muds didn’t like the seasonal go-getters upsetting their status quo.

Fortunately, with a few exceptions, the seasonal maintenance employees were much more open minded and I made several good friends who were in that faction. Foremost of these friends was Larry Lewis. Larry was a Vietnam veteran who also grew up in Michigan. He was a unique character. He drove a 1950s era Dodge Power Wagon van that he rebuilt. He still suffered from an intestinal infection he caught in Vietnam. As a result of complications (gas) from this malady, he had acquired the nickname, Captain Filth. Larry would give you the shirt off his back. He was the center of normalcy in West Unit’s work force.

Unfortunately, I also made enemies. The Trail Crew Foreman took an immediate dislike to me. Early on he called me a “stinking wet back.” Another time, I walked into his shop looking for my boss. I heard a bunch of people talking and laughing and figured that was his likely location. The Trail Crew Forman, saw me, stood up and, in front of the trail crew and the other Backcountry Rangers blurted out, “who the f$&k do you think you are coming into my shop?” He frequently told his buddy, my boss, that he should get rid of me. A fact that my boss mentioned to me with a deadpan look on his face more than once.

I remembered my Italian relative, Joe DePaulo, telling me stories about the abuse he experienced when he first moved to America in the early 1900s. If he could take being called a “stinking wop” and being assaulted with snowballs and fists, I figured I had it much better than a true immigrant.

The trail crew, composed stick-in-the-mud fraternity brothers/ski bums types, followed their boss’ lead and ostracized me out of their consciousness. While this might sound emotionally distressing, I found it reassuring as I had little respect for or interest in sharing their party-hard lifestyle. Still, the closeness of the Trail Crew Foreman and my boss was distressing. First, the animosity was unfair and, second, it was potentially troublesome. I would need a good recommendation from my boss at the end of the season if I had any hope of securing a seasonal job next year.

Backcountry Rangers a Community of None

I was one of five seasonal Backcountry Rangers assigned to the West Unit. Each of us was assigned to patrol in a different drainage for the Summer. Three of us were in our early twenties and two were in their fifties. The job description required us to spend five days a week patrolling our backcountry area. This invariably required us to spend four nights a week in the backcountry.

My first experience with Backcountry Rangers was at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. The Backcountry Rangers in those parks had established Ranger Stations that ranged from comfortable cabins to wall tents on platforms with screen doors and wood stoves. The Backcountry Rangers spent from three to four months at their duty stations. Many of those Rangers came back year after year to man their posts. They were supported by the Sierra Ranger District staff, supplied by helicopter and treated as the cream of the park’s seasonal employees. They were top line professionals. When I accepted the position, I expected no less support at Rocky Mountain and that my fellow Rangers would also be top notch professionals.

However, it became clear almost immediately that things were different at Rocky Mountain National Park. The backcountry crew was not the cream of the crop and the support they received was nearly nonexistent. Three of my fellow Backcountry Rangers did not have my romantic expectations. For them, it was just another annoying job, albeit a job with little supervision from above which allowed them to do as little as they wanted. For example, they really had no interest in spending their evenings in the backcountry. In fact, one, a Saint Louis school teacher, was deathly afraid of bears and never spent a night out in the backcountry that summer to my knowledge. I dubbed him and his two compatriots the “so-called” Backcountry Rangers. The so-called group despised the two of us that spent our duty weeks in the backcountry because “you make us look bad.”

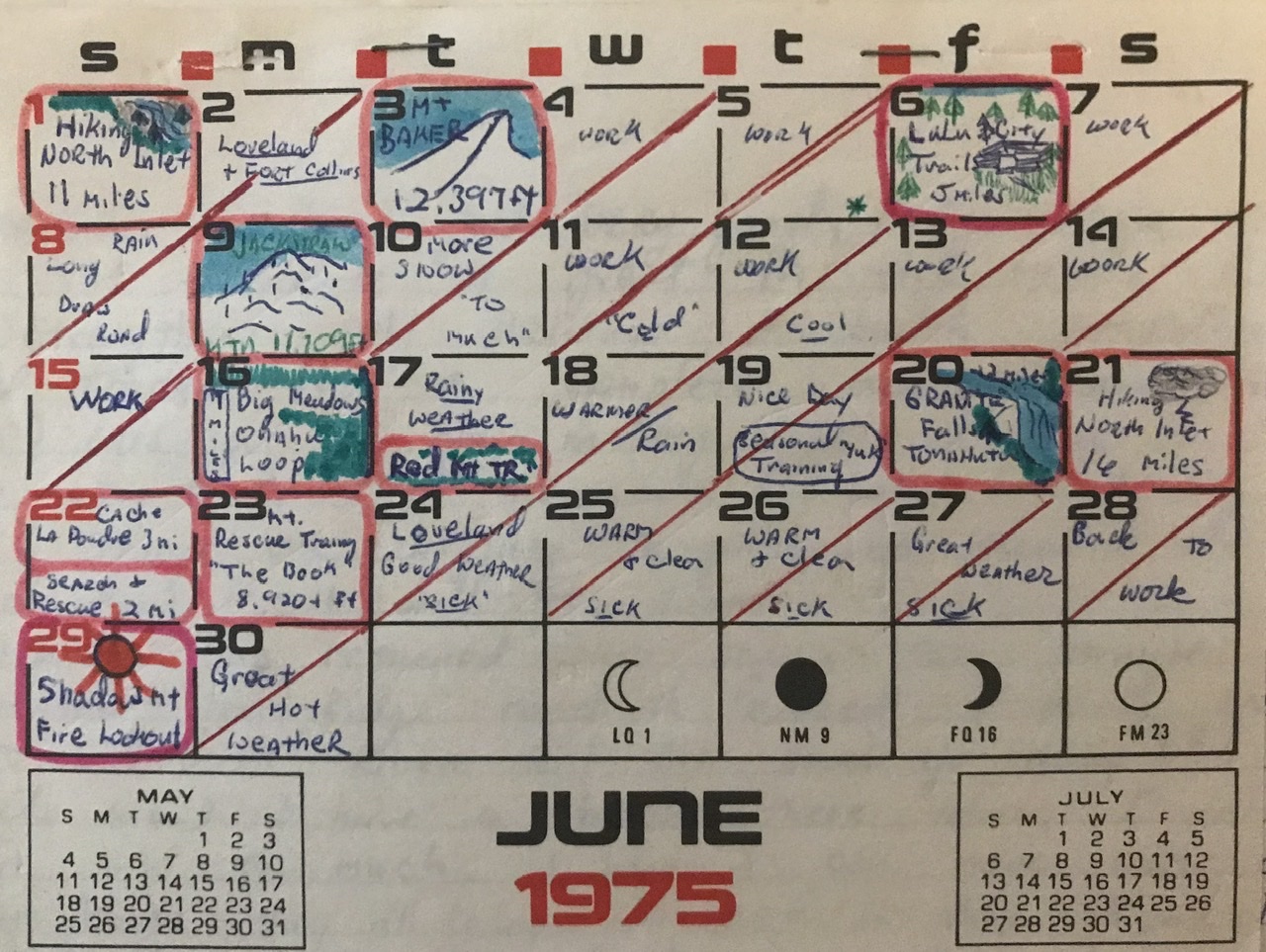

June—This and That

June was a mixed bag. The weather was mostly good but it did snow a couple of times. Trail patrol work was limited to lower elevation, snow free trails and impacted by training sessions and other work commitments. Additionally, I caught a nasty head cold that hung on for a week or more. I managed to climb a few peaks on my days off. Baker Mountain, 12,397 feet, in the Never Summer Mountains, was the most notable of these climbs. It was a windy day and the route involved suffering through lots of deep, unconsolidated snow. Jackstraw Mountain was another snowy climb on a snowy day. I also took part in a search and rescue operation which involved carrying an injured hiker out on a stretcher. It took eight of us to complete the task. The next day we all attended search and rescue training on the east side of the park. Timing is everything. All month I longed for the backcountry to melt out so I could move to my patrol area.

My Patrol Area

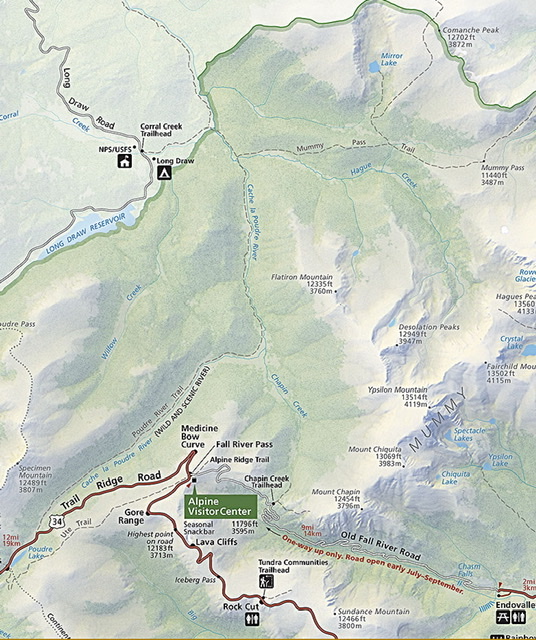

My backcountry patrol area was known as the Mummy-Milner backcountry area. It was the biggest patrol area in the park, comprising the entire northwest corner of the park. The Mummy Range formed the area’s eastern boundary. The Mummy Range is a high, windswept range that reaches above 13,000,feet. The range has a number of thirteen thousand foot peaks, including Mummy Mountain, Fairchild Mountain and Ypsilon Mountain. It was a big, exposed land capped by alpine tundra. The trailess Desolation Range, a small offshoot of the Mummy Range, and Trail Ridge Road formed the area’s southern boundary. The park’s northern and western boundaries formed the other two sides. These boundaries encompassed the Cache LaPoudre and Hauge Creek drainages. The Cache la Poudre River drainage was a long, wide valley with meadows, abundant willow thickets, beaver dams and thick forest. The Hague Creek drainage transitioned from meadow to forest to tundra as it ascended from west to east. Unlike the east side of the park, Trail Ridge Road and the area near Grand Lake, Colorado, my patrol area was lightly visited.

My patrol area was the largest in the park. It covered the Cache and LaPoudre drainage which was essentially all of the northwest corner of the park.

My area contained only three trails, two of which were seldom used. The Cache La Poudre River trail begins where Trail Ridge Road crosses Milner Pass. From the pass it descends down the Cache la Poudre River valley to the Mummy Pass trail junction. The Cache la Poudre River Trail saw so little use that in 1975 much of its tread had disappeared. This fact was unknown to my boss, the West Unit Backcountry Ranger, because he had never traveled its length.

A second access route was via the Chapin Trail. This trail descended from Chapin Pass to the Cache la Poudre River. The trail was accessed from the Old Fall River Road, a one way, gravel road, that made trailhead access difficult. Additionally, anyone interested in starting and ending from Chapin Pass would face a stiff uphill climb on their return. So, few people used this trail (and, as of 2020, it appears that it is no longer maintained).

The Mummy Pass Trail was the main thoroughfare through my patrol area. It started at the Corral Park Trailhead on the northwest corner of the park. This trailhead was located on a dirt road that lead from the Front Range’s eastern slopes to La Poudre Pass. From the trailhead, the trail descended down to the Cache la Poudre River and ascended up Hague Creek to Mummy Pass. A side trail left this trail and provided access to Mirror Lake. Since there was no Park Service office situated on the northwest corner, people entering the park from that trailhead often did not have a permit. Mirror Lake, which in 1975 was not part of the park, was the destination for the vast majority of hikers using the Mummy Pass trail. In fact, I rarely encountered hikers between the Mirror Lake junction and Mummy Pass. Since Mirror Lake was managed by the Roosevelt National Forest but was only accessible by traveling through the park, it was a management problem which was delegated to me.

July—The Backcountry Opens

Finally, after six weeks on the job, the majority of the snow melted and I was able to take my first patrol into my area. On July 2nd, I hiked from Trail Ridge Road at Milner Pass down the Cache la Poudre. I was surprised that the trail shown on the map did not exist for much of the first four miles as lack of maintenance, the lush meadows and lack of use were not amenable to the trail’s tread surviving. This was not a navigational problem since the route simply linked up open meadows. When I reached the point where Chapin Creek joined my route I finally found a good tread.

My Cache La Poudre Camp

It was determined that I would set up a camp at the confluence of the Cache la Poudre River and Hague Creek. My camp was only four miles from the Corral Park Trailhead. It was nine miles to my camp from the Milner Pass Trailhead on Trail Ridge Road.

The next day the park’s outfitters arrived with a pack string with my camp equipment. After helping me set up the tent, the outfitters rode away, vaguely promising to come back someday and build a pit toilet.

When I was hired I was promised a backcountry camp with a wall tent on a wooden platform and a picnic table. The promise was not kept. Instead I was given an old, medium size, circular canvass surplus army tent. The tent had one zipperless door, no windows and no mosquito netting for the door. While I could have complained, I was able to fashion a comfortable, albeit cavern-like weather tight camp. After six weeks stuck in the front country I was delighted to be on my own. A month late the outfitter returned and built a pit toilet.

Backcountry Ranger Job Description

I was told my first duty as the Mummy-Milner Backcountry Ranger was to enforce the law. “The West Unit Manager wants hikers in your area to obey the law.” my boss explained as he leaned back in his chair cleaning his finger nails with a pocket knife. “You’ll be rated by how many tickets you write,” he added.

Yes, as a backcountry ranger I had to carry a ticket book and enforce the law. I was expected to ensure hikers had a wilderness permit. If they did not, I had to turn them back. If they gave me trouble I had to give them a Federal citation. If they had a dog, I had to ticket them and turn them around. Although I was required to carry a heavy, bulky walkie talkie at all times, there was no radio coverage in my patrol area. I was truly off the grid. The radio proved to be useful for bluffing irate recipients of citations as I could threaten to call in backup. Fortunately, no one ever called my bluff. That was the downside of my job.

The good side was that I was able to spend most of July in the backcountry, hiking many miles and occasionally climbing a peak. Fall Mountain, 12,258 feet, in the Mummy Range was just outside of my patrol area but was close enough that I continued on to its summit. I figured I could justify it as an effort to find radio coverage. In sum, I spent 19 days at my backcountry camp. The July weather was the best of the entire summer.

I also managed to hike on one of my days off and climbed Specimen Mountain, 12,489 feet. Of course, I had to spend some time each weekend doing laundry and buying food for the next week. Grand Lake, Colorado which is just south of the park’s southwest boundary was a typical resort town with lots of gift shops, restaurants and tourists. Everything cost a lot more, so I often drove to Boulder or Fort Collins for supplies.

The Mirror Lake Troll

As I mentioned earlier, in 1975, for some unexplained reason, Mirror Lake was not included within the park’s original boundaries. The only way to get to the lake was to hike through the park. The lake was the pristine mountain lake and a popular destination, especially for college age citizens of Fort Collins, Colorado.

As most people know, the Park Service does not allow dogs on its trails. Since Mirror Lake was on Forest Service land and the northwest corner of the park had a reputation of being infrequently patrolled I found myself in the position of having to enforce the no dogs allowed rule too often. At first, I would simply turn hikers with dogs around and suggest they hike someplace else. Eventually, I had to follow orders and start writing tickets for each offender. After writing two dozen or so tickets, the hikers with dogs became a thing of the past.

I was down in Fort Collins on my days off buying groceries when I overheard the following conversation in the checkout lane.

Clerk: “Jill what are you doing this weekend?”

Customer: “We are going to hike into Mirror Lake.”

Clerk: “Don’t take your dog, the Mirror Lake Troll will write you a ticket and send you home.”

Customer: “That sucks!”

Although I recognized the clerk who I had busted earlier, she did not recognize me. I was glad the “no dogs” word had spread. It was one less unpleasant confrontation I was spared.

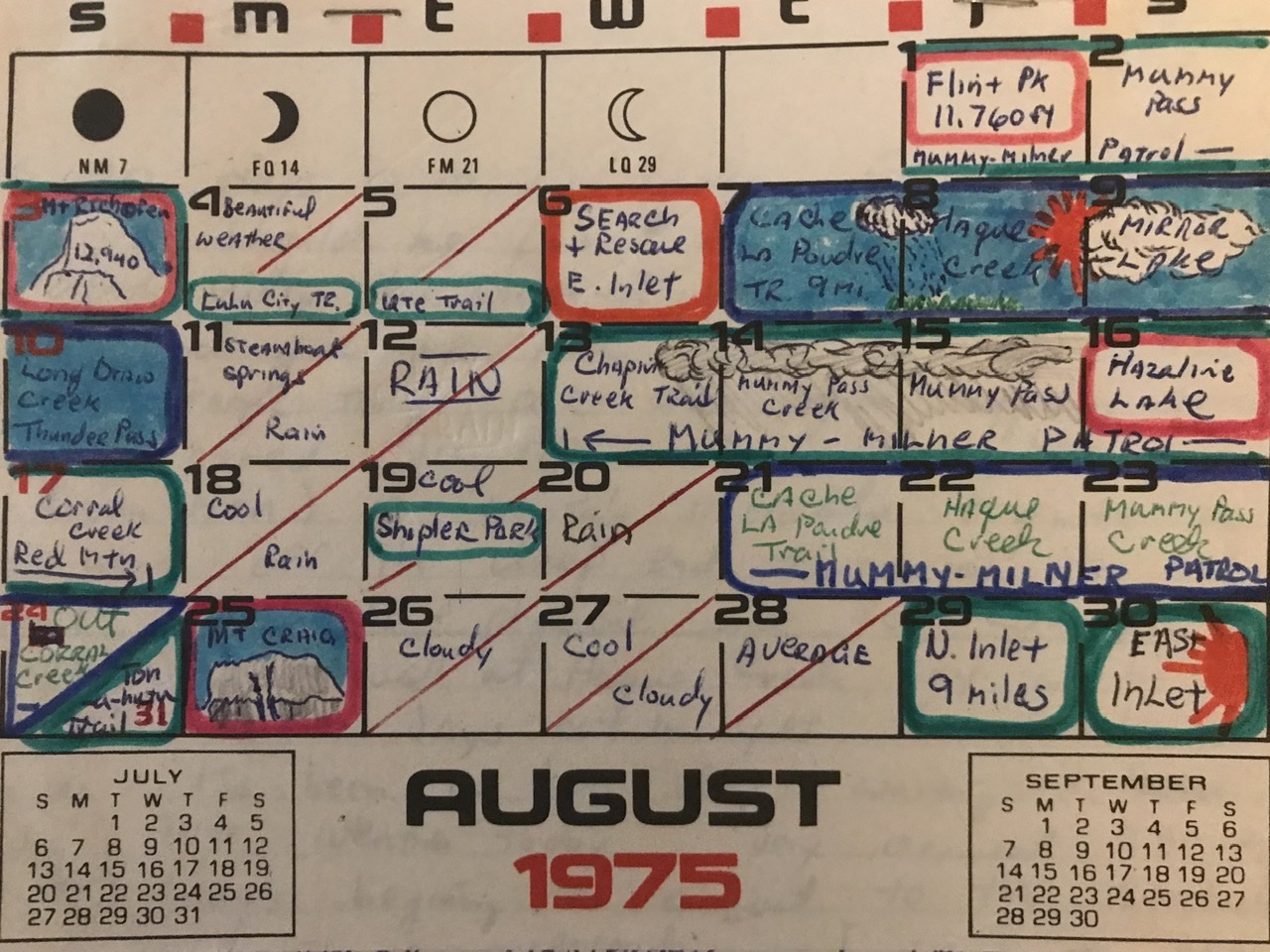

August

It rained almost every day in August. Somedays the rain was limited to afternoon thundershowers but often it just rained most of the day. The Monsoon season was new to me. I learned that the Colorado Monsoon season varies in intensity and length from year to year. It can occur any time from June through September. In 1975 there were only a few thunderstorms in July but the Monsoon really fired up in August. The Monsoon is powered by solar heating in the Midwest and Southeastern United States which causes a clockwise circulation pattern to form. This circulation draws moisture to Colorado from the south. The moist air rises up over the mountains and builds into towering thunderheads. The incessant rain did knock down the swarms of mosquitos that plagued the park in July. The rain also deterred hikers from venturing into my patrol area. The storms frequency made it difficult to patrol above treeline as it often stormed by 10:00am.

I managed to climb Peak 12716 (Comanche Peak Wilderness HP), in the Mummy Range early in the month as well as Mount Richthofen in the Never Summer Mountains two days later. At the end of the first week of August I was surprised when a voice came out of my radio. Wendy, the La Poudre Pass Backcountry Ranger, had driven to the Corral Park Trailhead to make radio contact. He requested my help. Early the next day, I hiked out to the road where Wendy picked me up.

Wendy, who was a long time seasonal, manned the La Poudre Pass Ranger Station which was located on the Continental Divide at La Poudre Pass in the Never Summer Mountains. He was responsible for patrolling the Never Summer Range backcountry. He had a nice cabin and a pickup truck. He managed a truly unique type of backcountry.

The Never Summer Mountains are a small, extremely scenic Continental Divide mountain range which forms part of the western boundary of Rocky Mountain National Park. There are 17 named peaks in the range. Mount Richthofen at 12,951 feet is the highest peak. It is part of the Continental Divide but a bit confusing physically because the east side of the range drains west into Colorado River Basin.

Thanks to human intervention water is collected from the range and transported across the Continental Divide at La Poudre Pass and deposited into the Atlantic Basin. This irrigation project to kidnap the water began in 1890 when a project named the Grand Ditch was started. The ditch is a scar that runs across the Never Summer Range’s eastern slopes from north to south at 10,000 feet for 16 miles, collecting water from the streams that drain the range’s peaks. The ditch was finished in 1936. A road, only open to the canal company and the Park Service, follows the canal for its entire distance.

Wendy’s message did not mention why I was needed. When he picked me up, he explained that my help was needed to guide a group of boy scouts up Mount Richthofen, 12,940 feet. It did not sound like an authorized task but I was always up for climbing a peak so I asked no questions. The scouts were tame by scout standards and we had a nice climb to Richthofens’s airy summit. We climbed the peak from Thunder Pass climbing over Static Peak, 12,580 and The Electrode, 12,018 feet.

My next patrol started late as I took part in a search and rescue operation in the East Inlet drainage. Once I was at my camp, now that ‘no dog” rule was fully implemented, I was tasked with marking the park boundary around Mirror Lake. This was a rather mundane task which allowed me to hang out at the lake for a couple of days.

Mid-month I was offered a position with the Peace Corp in Costa Rica. If I accepted, I would he assigned to the Costa Rican National Park Service. I would be a training instructor for park rangers. Based on the mixed bag of my experiences at Rocky Mountain, I thought a major change was in order. I accepted the position which would start in November. I quickly developed a “short-timer” attitude that would dog me the next four weeks.

The most enjoyable climb of the summer was an ascent of Mount Craig which is located up the East Inlet. I climbed the peak with Larry Lewis via the big gully on the north side of the peak’s west face. This route turned out to be more difficult than we bargained for as it included several Class 4 moves in the lower sections of the gully. On our descent, to avoid descending the Class 4 moves, we decided to try a different route. We started down the large cirque on the peak’s northeast side. The climbing was considerably easier but the route finding was time consuming. It made for a long day. We got back long after dark. It was on this climb that Larry and I planned a long backpacking trip in the Sierra Nevada Mountains which would take place as soon as our appointments ended but that is another story (A Sierra Fall Backpack).

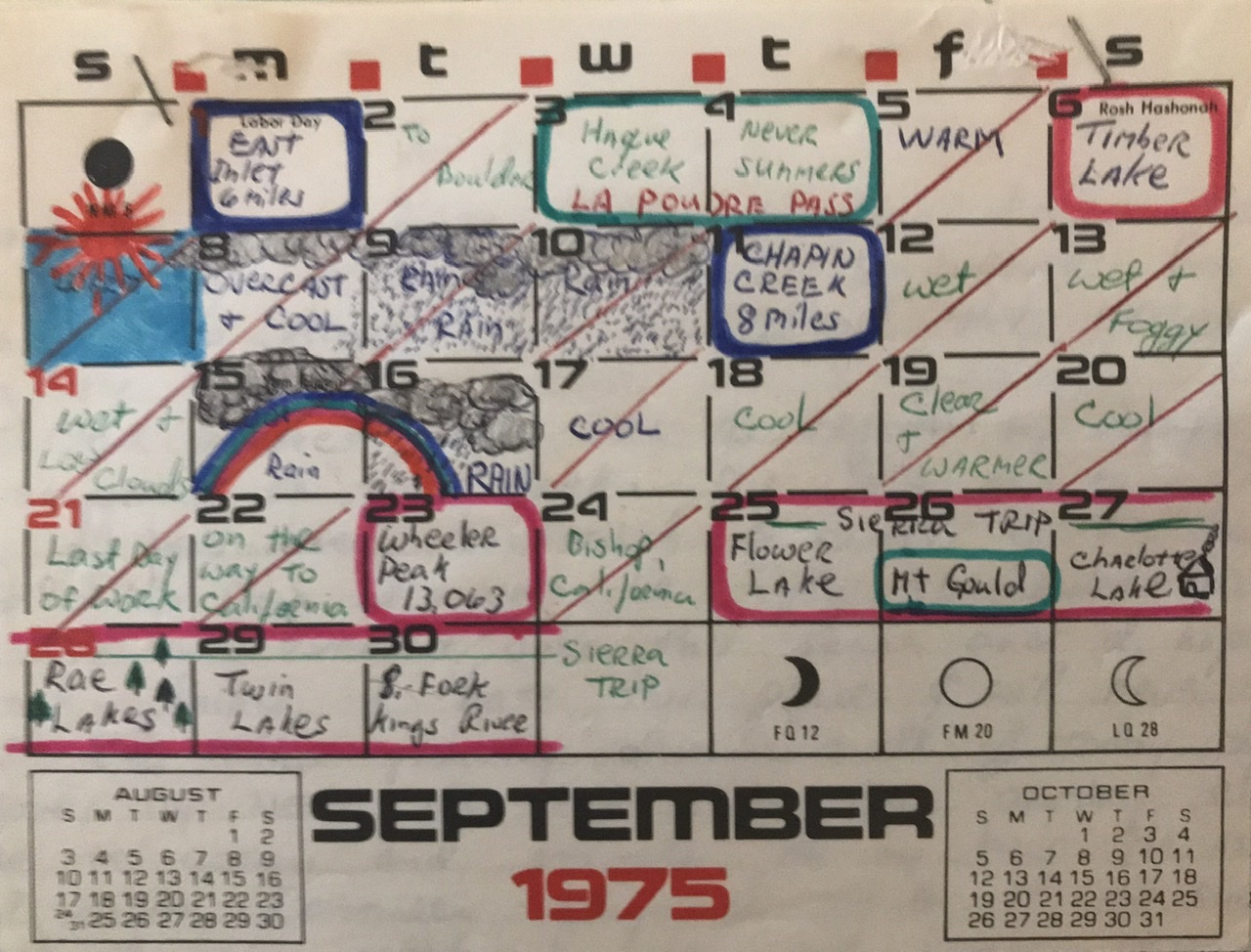

September

September 14th was my last scheduled work day. Wendy and I were the only two Backcountry Rangers still on the payroll when the month started. I was directed to close up my camp after Labor Day. As usual, I was not provided any help. I packed the tent and tarp into a storage container that an outfitter had dropped off earlier. It wasn’t waterproof or mouse proof. I suspect the 1976 Backcountry Ranger found the tent destroyed. I loaded up the remaining gear as directed and lugged the hundred pound plus load out to the Corral Creek Trailhead. Wendy picked me up and drove me back to the front country. Just like that, my Mummy-Milner gig was over.

I still had a few work days left but my heart was not in it. I was anxious to get on with a planned trip with Larry to the Sierra Nevada and then to prepare for my Peace Corp assignment.

Tommy of Mayberry

The most notable September event occurred during my last week. I arrived at the backcountry office at 7:00am packed and ready to head out to patrol the East Inlet trails. My boss was sitting in his usual position behind his desk, feet up on the desk top and his hands clasped behind his head. His boss, the District Ranger, was looking out the window and talking stridently. “Liles wants this stopped today,” he said.

The seasonal Road Patrol Ranger who usually started his day at Noon was sitting in the corner. My boss, had a smirk on his face. Although everyone knew my boss despised the District Ranger, the District Ranger was clueless of this fact.

When I said “good morning” they both turned and looked my way.

My boss sat up, “You’re not going out today,” he said.

“What’s up?” I asked.

The District Ranger chimed in, “Have you had fire arms training yet?”

“No?” I had received law enforcement training at both Crater Lake and Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks but my training never included handling firearms or making arrests.

“Well, no time for that now,” he responded handing me a pistol. He then proceeded to explain the situation ala Jack Webb’s Joe Friday character from television’s Dragnet police show. My boss put his head in his hands, face looking down at his desk top.

It seems that while I was busting backpackers with dogs, bigger crimes were roiling the front country. A gang of “car clouters,” the Park Service’s slang for criminals that broke into visitors’ cars at trailheads, was wreaking havoc on front country parking lots. This problem is endemic to National Parks parking lots. This particular series of thefts had been occurring regularly for the last two weeks.

“He is tired of filling out crime reports,” my boss interrupted the narrative.

The plan was to have me stationed in the bushes at a popular trailhead. I would be armed with the pistol and my walkie talkie. Another seasonal, who normally worked at the entrance station, would be at a second trailhead about a mile away. While we were hiding in the bushes, the District Ranger and the seasonal Road Patrol ranger, both certified law enforcement officers, would be standing by in patrol cars nearby.

We were given a one word code to use to report on the radio if we observed a criminal breaking into a car. I took my radio, lunch and a water bottle out of my daypack and put them into a stuff sack. I didn’t know what to do with the gun. “Do you want me to shoot them,” I asked dumbfounded?

“Only if you want to,” my boss chuckled.

“This is serious business Lopez,” the District Ranger cautioned, “let’s take it for what it is.”

Twenty minutes later I was sitting on the ground in the trees watching the ten space trailhead parking lot which was devoid of vehicles. Remember this was a Thursday, after Labor Day in September in 1975. The west side of the park was anything but busy. By ten o’clock only three cars had stopped at the parking lot and the occupants had only momentarily stopped to use the restroom. A Park Service maintenance truck pulled into the parking lot. It was my buddy, Captain Filth, stopping to empty the trash cans and clean the restrooms.

Twenty minutes later I was sitting on the ground in the trees watching the ten space trailhead parking lot which was devoid of vehicles. Remember this was a Thursday, after Labor Day in September in 1975. The west side of the park was anything but busy. By ten o’clock only three cars had stopped at the parking lot and the occupants had only momentarily stopped to use the restroom. A Park Service maintenance truck pulled into the parking lot. It was my buddy, Captain Filth, stopping to empty the trash cans and clean the restrooms.

“Pst, Larry,” I called out from the bushes. Larry looked around confusedly at the empty parking lot. “Over here,” I said. Larry walked over to my hiding spot.

“Who you hiding from?”

I explained the stake out details and we both had a good laugh because we thought it was unlikely we would catch anyone breaking into cars when there were no cars in the parking lot. Additionally, the thought of me pulling a gun on a gang of thieves was as comical as it was potentially dangerous.

“Did they give you a gun with bullets,” Larry asked.

“I don’t know, I better look,” and we both laughed. There were bullets in the pistol.

“Well, they trust you more than Sheriff Taylor trusted Barney Fife,” Larry dead panned.

About this time, we decided Larry’s Park Service truck in the parking lot would deter car clouters from stopping to break into the cars. Larry said “I hear Aunt Bea calling,” and he walked off to finish his maintenance work.

“Bye Opie,“ I said.

I resumed my watch. Around Noon while I was eating my lunch, a couple of cars did pull into the parking lot and the occupants got out and started up the trail. Finally, there was bait to tempt the criminals. I became more attentive as well as concerned. A few more cars pulled in and out over the next hour or so. None of these visitors were interested in anything other than the restrooms.

Around 3:00pm the seasonal road Patrol Ranger pulled into the parking lot with red lights flashing. This was the signal that they had caught someone at the other trailhead. I came out from my hiding place and got in the patrol car.

“They caught em,” the Ranger said excitedly. We drove to the second trailhead where we found the District Ranger and three culprits as well as a car with its passenger side window smashed.

The culprits were all handcuffed. One was a young girl who looked to be sixteen. The second was an out-of-shape guy of maybe thirty, droopy mustache and scraggly hair. The third was a woman with a hard, defiant look on her face which was directed at her scraggly accomplice. None of them said anything as they were questioned but her face expressed her unhappiness with the guy.

“Put him in the back of my car,” the District Ranger directed me. I took a hold of the guy’s arm and as we passed by the woman, she stepped toward me and yelled “boo.” I nearly fell over I was so startled.

Later, back at the backcountry office, the District Ranger was elated as he recounted the day’s events to my boss, who didn’t look like he had moved an inch since we left him in the morning. I returned the pistol, hopeful that my stake out days were done forever.

This is the End—Finally

All told between May 15th and September 11th I spent 60 days patrolling trails, covering 458 miles in the park and climbed 12 peaks. I also issued 25 citations and chased numerous permit-less hikers out of the park. The backcountry experience was not what I expected when I took the job. Nevertheless, it was a good experience which increased my self confidence and wilderness skills. The front country duty was a learning experience that I did want to repeat at Rocky Mountain National Park.

NEXT: A Sierra Fall Backpack, 1975, California