Carl Sheets and I had made several Winter climbing attempts before the Spring of 1974 including Mount Borah, Mount Heyburn and Grandjean Peak. On all 3 peaks, we encountered deep, unconsolidated snow that made travel slow and greatly increased the risk of avalanches. We did not have avalanche gear and snow science was in its infancy, so good judgment and knowledge of snow conditions were all that we could rely upon.

The Winter approach to Mount Heyburn was around 7 miles and Grandjean Peak over 15 miles, which we did on skis. Although we were unsuccessful in bagging a summit on these trips, we gained valuable experience with Winter camping and snow travel. Tired of the long, trail-breaking slogs and the cold of mid-Winter, we decided to wait until Spring after the snow had consolidated before making another attempt at a summit.

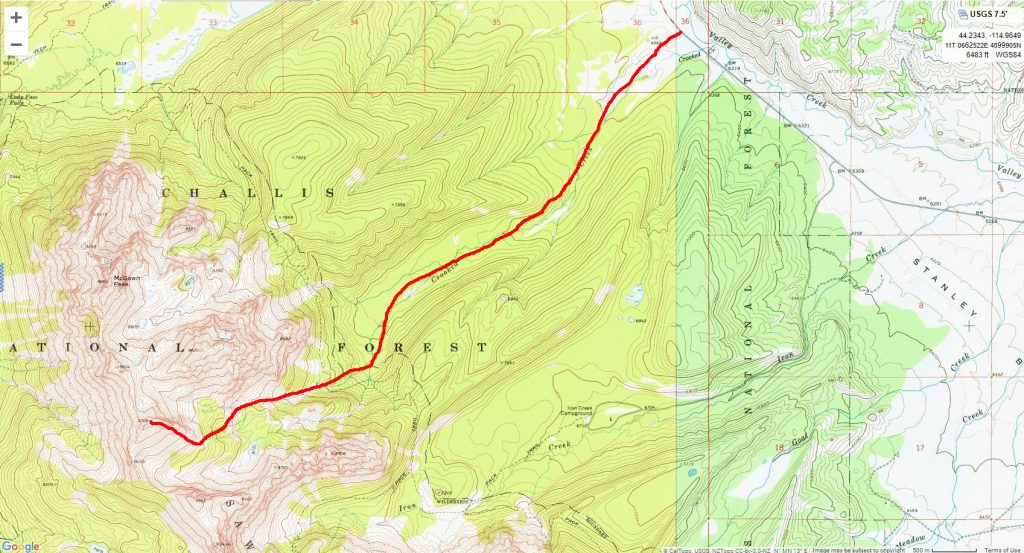

ID-21 over Banner Summit was closed in Winter and was not usually plowed until Memorial Day weekend. Thus we made the longer drive through Ketchum over Galena Summit to travel to Stanley. We didn’t have a specific starting point or a summit in mind on this trip. Finding a parking spot along with a safe and reasonable approach to the mountains were our primary objectives. After leaving Stanley, we drove north on ID-21 surveying the Sawtooth front and watching for a plowed turnout. We found what we were looking for at the Crooked Creek turnout. We parked my 1959 Ford Wagon at a wide spot, loaded up our gear, strapped on our skis and began the long climb to the peaks.

Before climbing skins became popular, klister wax was the standard for snow that had transitioned. Some people hated klister. It was a semi-liquid, glue-like material that would adhere to absolutely anything it touched. However, through experience, we found that the right klister (properly applied) was like magic. It allowed one to walk straight up without fear of back-slipping, yet released and glided with ease on flats and downhills. On this trip, we nailed the wax combination so up we went.

On the steep sections, we side-stepped and traversed. We steadily climbed about 5 miles on our first day–good mileage considering that we were carrying 60+ pound Winter-equipped packs each. Our Winter climbing strategy was to set up a base camp and, from there, make lightweight day trips to the nearby peaks. We scouted and found a relatively flat spot with firm snow and erected our temporary Winter home. The weather was still Winter-like the first day but the next morning brought beautiful clear skies and little wind.

The hardest part of Winter camping is finding the desire to climb out of a cozy, warm, goose-down sleeping bag early on a bitter cold morning. To make it tolerable, we freed only our heads and arms and lit both of our Svea stoves until the tent had warmed up a bit. Then we would cook and eat breakfast in our bags and only emerge when we were ready to dress and go. Try as we could to keep our leather boots warm all night, they always seemed frozen in the morning. In a final act of defying the cold, we got up, stomped on our frozen boots and started our approach to our objective.

The Sawtooth Range was heavily corniced this Spring so we picked Peak 9709, which was clear of the fall line and had a reasonably safe-looking approach. Traveling with little weight, we made good time getting to the bottom of the East Ridge of the peak that we had picked to climb. We climbed as high as we could on skis and switched to boot travel and ice axes where the ridge steepened. The snow conditions were firm, and we made good time climbing the ridge. Soon after, we were both standing on the summit. As if to be rewarded for our persistence, we had a bluebird Spring day in the Sawtooths with the ski run back to camp as the icing on the cake.

Carl surveying the route on our approach to base camp. We had state-of-the-art JanSport aluminum-frame packs that were a vast improvement over the wood-framed Army surplus packs that were still in use in the 1960s and early 1970s. I had the standard workhorse of backcountry skis–the Bonna 2400 with lignostone edges. Our bindings were the Silvretta cable bindings with a universal toe that allowed for the use of any stiff-soled mountain boot. Some people reported cable breakage with the Silvretta bindings, but we never had any problems. Bob Boyles Photo

Our base camp high above Stanley Basin. High-quality outdoor gear was limited and expensive in the early 1970s so we got some of ours from Frostline, a company that offered sew-your-own kits. The tent is a Frostline Kodiak that came with instructions for 2 different methods of sewing. The one we choose was the more difficult. We somehow talked my sister into sewing the tent. It took the 3 of us a month to complete. It turned out to be the best Winter tent I’ve ever used due to good ventilation and the low snow shedding profile. We ended up using it for the next 10 years. Bob Boyles Photo

Carl and Bob decked out in the standard Winter gear of the time–wool and down. I used a tripod and a timed exposure to produce this early version of a “selfie.” Bob Boyles Photo