Glissading firm snow and going “way too fast,” I tripped and did a couple of fast-forward somersaults. Rolling out of the second somersault, I planted the pick of my ice axe deep in the snow. It was a perfect “ice axe self-arrest” for about a second–then the axe ripped out of my hands but stayed attached to my wrist.

As I started somersaulting again, the ice axe became a flail. It first smacked a hard blow between my eyes then in mid-roll, the spike got very close to my stomach. Somehow I grabbed the shaft again, planted the pick a little less firmly and managed to stop.

I had a minor scalp wound that bled wonderfully but otherwise was uninjured. Wow, I thought, my first climbing accident! It was mid-June 1971. Gordon Williams, Harry Bowron, a tough little blond named Janet and I were descending miles of snowfields. We had just spent 2 days approaching and climbing an easy route up the back side of Thompson Peak (10,776 feet), the highest pile of choss in Idaho’s Sawtooth Range.

From near Thompson Peak, some of the more interesting technical peaks of the Sawtooths dominate the southwest skyline. We only knew the name of one–Warbonnet. Worse yet, we didn’t know which peak was Warbonnet but we had a new “must go, must climb” objective. I loved them all!

Soon there was a second reason for me to climb in the Warbonnet area. It was the home of the “lost crystal cave.”

During Summer, I worked for the Forest Service in the Sawtooth National Forest in my college years. Just after the Thompson Peak climb, the Forest Service had me haul some supplies (and a requested bottle of whiskey) up to an isolated Forest Service “Guard Station” for an old employee named Jim. I got there late and after unloading supplies, Jim invited me to have dinner with him. After food and a little whiskey, I asked him what he knew about the Warbonnet area. He was a little reluctant to talk at first but, with a “wee bit” more whiskey, he shared some very interesting information.

His father had been a horse-packer and guide for some 1930s Sawtooth climbers.

Jim explained that his father had gotten a taste for climbing but also had found crystals. “Crystals”? I said, leaning forward. Jim straightened up and nearly shouted, “Yah, quartz crystals, certain spots are full of them: big ones—-some are huge! There’s a bunch around Warbonnet.” Jim’s voice got lower. “Give me some more of that ‘nerve tonic’ and I’ll tell you a true story about my old man and Sawtooth crystals.” After taking a long deep sip of whiskey, Jim told the story. “During World War II, quartz crystals were worth good money as radio crystals. I got drafted but my father hiked the Sawtooths and brought out a lot of those crystals.”

“Late one Fall, my father was crystal hunting up in the Warbonnet area. He had to do some pretty hard climbing but finally fetched up below a cave full of crystals.” Jim shook his head ruefully. “Dad told me, there was a big snowstorm coming but he climbed up into that cave anyway, even though he wasn’t sure if he could climb back down to get out.” Jim explained that the cave had many beautiful crystals but they were too big to carry out. All of the quartz crystals were 2-3 feet long and weighed hundreds of pounds. His dad anchored a rope around a big one and rappelled out of the cave into a blinding snowstorm. After many close-calls in the heavy snows, his father stumbled through the front door of his cabin 3 days later.

“Dad never went back to the Sawtooths again and I was always scared of heights,” Jim added. Jim clapped me on the back! “That crystal cave is still up there youngster—right near Warbonnet!” The next morning, as I was leaving to go back to my ranger station, Jim shook hands and said, “You be careful up in that Warbonnet area. My old man thought the storms up there were the worst he had ever seen.” Please note: collecting mineral specimens has been illegal in the Sawtooths since 1990 and quartz crystals now have no industrial value.

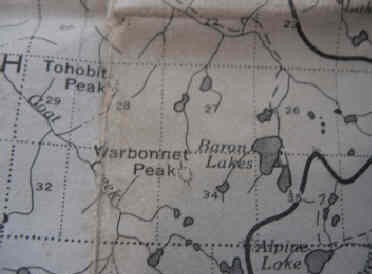

Later that Summer, Harry Bowron and I made a 12-day climbing trip into the Warbonnet area. We had some handicaps unfamiliar to many climbers these days. The only maps available did not show any details of the mountains in the area. There was no guidebook or “topos.” On the plus side, there was a good Forest Service trail and Harry (a NOLS course graduate and fearless leader) had gotten me “up to speed” (for 1971 Idaho) on technical rock climbing.

The first part of our 12-day trip was 2 1/2 days of hiking into, exploring possible routes and then climbing Mount Heyburn near Redfish Lake.

Ray on the North Face Couloir of Mount Heyburn. Millet pack, REI Helmet, Stubai “Nanga Parbat” axe and a 120-foot rope. We didn’t want to get the rope wet on snow so we didn’t use it until we got on rock.

We then took a day to trudge the long way into Baron Lakes up the Redfish Lake Creek Trail. It was “a grunt” with 65-pound loads which were dubbed “Sawtooth Overloads.” No freeze-dried food for us. We were laden with rice, macaroni and beans, along with Harry’s beloved aluminum pressure cooker.

Ray and Harry at the Baron/Redfish Divide in July 1971. From that divide, we had a close-up view of the many crags north of Baron Lakes.

We hiked down to the Upper Baron Lake and, the next day, began our climbing. For our first ascent, we picked a striking tower with a pronounced hook.

We scrambled up toward the overhanging spire and finally roped up 30 feet below the summit. Harry made me give him a shoulder stand and later employed a RURP (postage stamp-sized piton) for an aid move. From the summit register, we learned that our pinnacle was called Fishhook Spire (now El Pima).

Looking up, I saw another tower that captured my imagination: the inaccessible monolith that was later named Bluebonnet Tower. I might not have known its name, but I wanted it–badly!

Harry on Fishhook Spire/El Pima with Bluebonnet Tower (on left at top) and Cirque Lake Peak (right).

First we had to deal with what we thought might be Warbonnet. Our candidate didn’t match where the Forest Service map said Warbonnet was, but it looked like a warbonnet. We smoked a little stuff, thought on the subject and decided that the map sucked. Damn it, this peak must be Warbonnet.

The next day, we worked up to the South Face of what we thought was Warbonnet and Harry picked one of the several steep shallow chimneys available. We scrambled to a belay platform up about 20 feet and then he grunted up about 70 feet, fighting his way past several evil little thorn bushes. At this point, a thunderstorm moved in. As the rain started, we retreated.

After that storm moved off, we worked ourselves along the base of the spire toward the East Side. After awhile, we found a steep ledge system that went up a line of weakness on the East Face. With careful route finding, we were able to think, scramble and occasionally stroll all the way up to the flawless summit block without roping up. I looked at the start of this route again in 2007 and could not believe that we climbed it unroped. At the top, we discovered a flawless and crackless 110-foot high summit block with some ancient, bent, hangerless ¼” bolts leading up it. We did not have the tools to climb it and scrambled back down as the sun was setting. I did demand the rope in a couple places on the way down.

The next day was a thunderstorm day. We alternated lazing about with hiding from lightning then pursuing more food by fishing and hunting mushrooms. We had now been out for 7 days and our low-calorie diet was starting to affect our energy. We were definitely losing weight and it was hard to think about anything but food. My journal notes that the fish were spawning and did not seem interested in our flies or lures. The next day we addressed a challenge to our west (Verita Ridge we learned later). The 3 towers of a buttress dominated our western horizon and we worked our way up their South Side to a long ridgeline.

At the Easternmost High Point on the ridge, there was a cairn with a mustard-jar summit register. It informed us that we were on the West Summit of Cirque Lake Peak. The Cirque Lake Peak name now applies to the next peak to the north. We worked west up the spiny ridge to where we could look west into Bead Lakes Basin. Pinnacles were everywhere and we soon found a photo opportunity.

Harry posing atop Verita Ridge.

After photo posing and some “boulder trundling,” we turned south toward the highest summit on Verita Ridge. Along the way, Harry down-climbed unroped into a notch in the ridge and took a little while figuring out moves down to a chockstone that bridged the gap. He then stood on a car-sized chockstone and gave directions as I down-climbed. The final direction was, “Don’t put too much weight on that handhold: it’s loose!”

There was no other handhold and little for my feet. Of course I pulled it out and dropped 6 feet butt-first onto the chockstone. The handhold followed and hit me on my helmet. Other than some butt bruises, no harm was done. I was a little jumpy the rest of the day and we got back to camp earlier than expected. Still thinking of nothing but food, I went fishing. Eureka! Two 20-inch Cutthroat Trout for dinner which helped a lot with the “calorie deficit.”

Full stomachs improved our morale a great deal and we decided to try another route on “our Warbonnet” early the next morning.

We were out of camp at first light and hiked/scrambled up lines of weakness on the Northeast Corner of “our Warbonnet” (Big Baron Spire) until we found a wide ledge that took us well out onto the North Face. Along the way, I found a perfect 4” x 8” quartz crystal. It was a ‘good omen’ and we carefully buried it then hiked on up. Maybe the “Crystal Cave” was above us?

We had scouted the start of this route 2 days previously and we were both impressed by the possibilities. Our rope-up ledge was about 500 feet above the start of the steep North Face and above us stretched an invitingly low-angled area that led up to vertical headwalls. We enjoyed 7 120-foot leads to the summit block. After 4 leads of lower-angled rock, the route took off up steep cracks. Harry improvised aiders and aided up part of one pitch. I couldn’t clean and follow it free but he felt bad that he had not “gone for it” and led it free. After we arrived at the “flawless summit block,” once again we stared up at the bent, hangerless bolts. An approaching thunderstorm chased us down before we could think of how to try the ancient bolt ladder.

The Warbonnet/Baron Lakes area is notorious for frequent and vigorous Summer thunderstorms. On the 1949 first ascent of the Big Baron Spire bolt ladder, Fred Beckey, Pete Schoening and Jack Schwabland had major problems with thunderstorms for 3 days. The climax storm nearly killed them during an epic retreat (through rain, hail and very close lightning strikes) from the “work in progress” summit-block bolt ladder. Although both Pete and Jack were injured as rain sluiced them off the mountain, they climbed back up the next day. They eventually placed 20 ¼” bolts on their way up the summit block.

On both of our ascents, we kept our eyes open for “the crystal cave” but never found a clue around our route other than the one perfect crystal and some broken fragments.

Approximate locations of our 1971 routes on Big Baron Spire (our Warbonnet). On the left is the route we scrambled to the summit. On the right is the “North Face cutoff.”

The next day we departed for another 3 days of Sawtooth Adventures to the south and east. However, that Winter we learned that the true Warbonnet was several miles north of our “imitation Warbonnet.” The peak that we had done 2 new routes on was “Big Baron Spire” and was also called “Old Smoothy.” Where could the “Crystal Cave” be?

I was not able to search for it again until August 1972. In 1972, Harry Bowron and I had planned on climbing in the Sawtooths during July and August. However, in mid-June, Harry was offered a job as a Middle Fork Salmon River boatman. He explained to his would-be employers that he would love to take the job. But if he accepted, his climbing partner would hunt him down and kill him. No problem. They would also train me to be a river guide too. We accepted and I never regretted the lost climbing time.

After the float season was over in late Summer 1972, Harry Bowron, David Thomas and I went into upper Goat Creek on the Southwest Side of Warbonnet in the Sawtooth Range. No trail goes into Goat Creek. On the way in, we climbed another big peak in the area–Packrat. From its summit, we were able to figure out where Warbonnet was and how to approach it.

Harry Bowron and David Thomas looked across at the East Ridge of Packrat. It was a scramble with the rope used only on the steepest part. This time we had no problem figuring out what peak was Warbonnet. We knew that there were climbing routes on it, but beyond knowing Warbonnet was within our capabilities, we had no idea where the established routes were.

This time we had no problem figuring out what peak was Warbonnet. We knew that there were climbing routes on it, but beyond knowing Warbonnet was within our capabilities, we had no idea where the established routes were.

This view is northeast to Warbonnet (upper right center) and Cirque Lake Towers (right).

At the time, Warbonnet (10,200 feet) had a reputation as one of the most remote and difficult peaks in the Sawtooth Range. It is still considered a remote technical climb, with the easiest route to the summit rated Class 5.4. The next day we climbed up to the high saddle on Warbonnet’s Southeast Side and decided to climb directly from there towards the summit. After scrambling up a ways, we had 2 leads of easy roped climbing with the route finding taking us out onto the East Face. We went diagonally up and north toward the huge summit overhangs until we finally came to hard climbing.

The East Face of Warbonnet with our “approximate” 1972 route in white. The white line ends at the chimney that splits the peak.

Ray on an early lead.

We arrived at a good ledge with much steeper rock above us. Harry was convinced that 2 jam cracks that went up a very steep slab would take us somewhere. He tried climbing the slab free and backed off, then aided up the cracks to where the angle eased. He went back to difficult (5.8?) free-climbing up to a cave right under the huge summit overhang. The cave turned out to be a giant chimney that splits the summit of Warbonnet. I remember some difficult free climbing with a pack on, getting off the slab and into the chimney. After that, it was no problem.

Harry’s aid lead onto easier slabs below the cave.

Harry leading in the giant chimney that splits the top of Warbonnet.

A view out the West Side of Warbonnet from the “giant chimney.”

The chimney took us to a big belay platform, just before the final lead to the summit. Ah yes! Was the chimney—the crystal cave? Unfortunately, there was no sign of crystals, although we did not descend into the much deeper West Side of the chimney. The summit lead was a “little bit airy” but I led it without difficulty. My old notes mention that there was one bolt for protection in 60 feet of climbing. I disapproved of the bolt but clipped into it. I would rate our route as 5.8 A1, but I think it would go free at a 5.9 or a low 5.10 level.

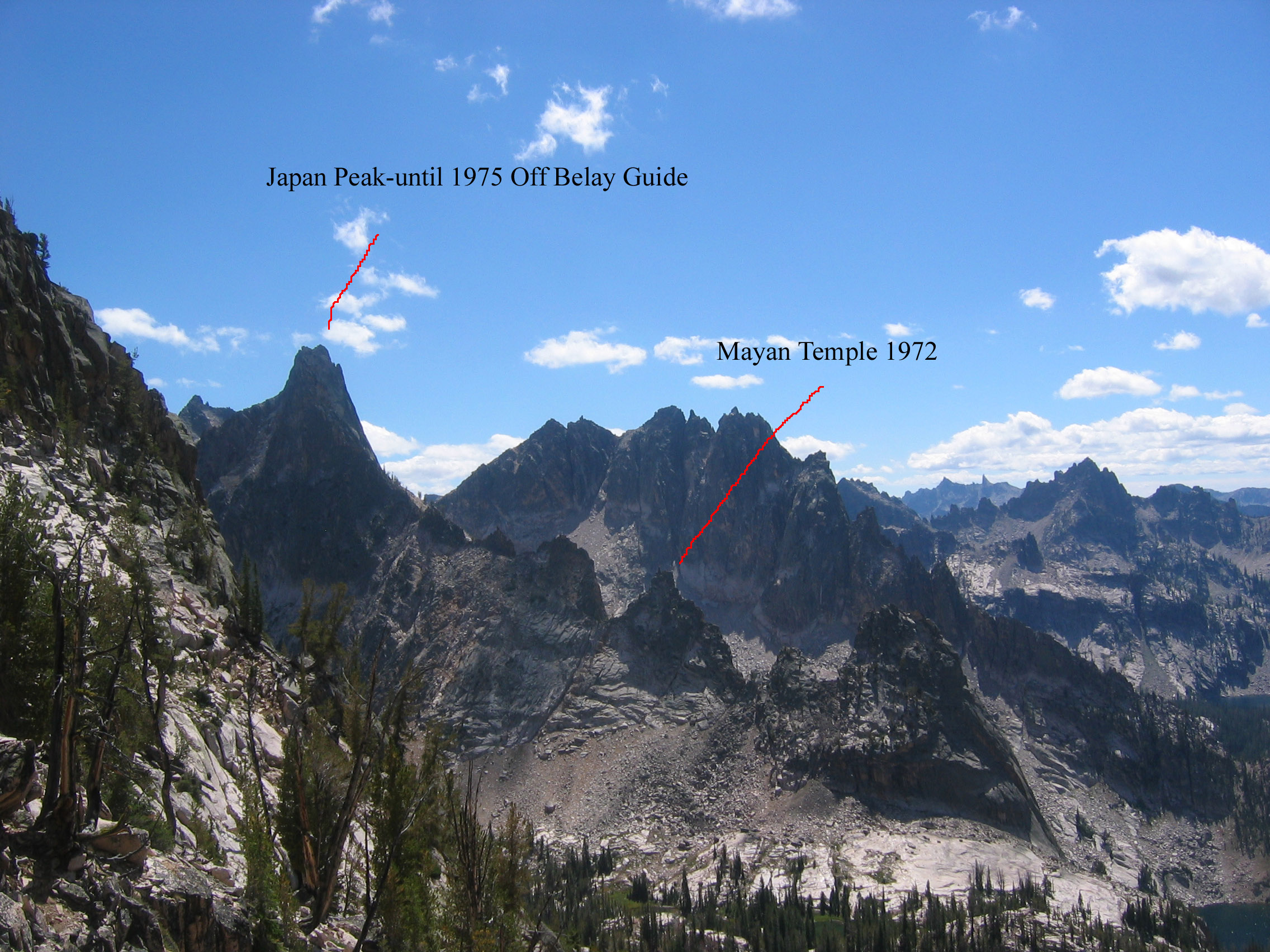

The next day Harry and I climbed a nice route on one of the minor pinnacles on the west side of our valley. I mention it because we thought it was a “first ascent” and we named the pinnacle “Mayan Temple” since it looked like one. We scrambled some of its East Face and then enjoyed 3 pleasant leads to a striking 15-foot high summit block.

On our way out, we ran into Louie Stur who was the “Godfather” of Sawtooth climbing. We told him of our adventures and he made note of the “First ascent of Mayan Temple.” Unfortunately, when the climbing magazine (Off Belay) did a Sawtooth Guidebook article in 1975, “Mayan Temple” was the new name of a nearby and much more formidable mountain previously named Japan Peak.

During 1973-76, I did not return to the Warbonnet area. I was running an outdoor shop 300 miles away in Northern Idaho and discovering climbing in Northern Idaho, the Cascades, Canada and even Yosemite. My mentor Harry had married, spawned babies and was “a pale shadow of his former climbing-whiz self.”

What about Bluebonnet Tower and the Lost Crystal Cave? They both gnawed at my soul. Would I ever find them? Finally, in Summer 1977, I was back with 2 friends. Mike Paine was a very good climber and Frank Michaels was always willing to give it a try. We packed “Sawtooth Overloads” up from Redfish Lake into Baron Lakes on Day 1. On Day 2, we examined options and decided that the first order of business was to free the 1971 route that Harry and I had done on what we now knew was Big Baron Spire. We now knew about the Beckey bolt ladder on the summit block and were ready to deal with that as well.

The North Face Bypass Route on Big Baron Spire. Follow low-angled slabs up to the steep area then escape up cracks to the right.

We fired up the route. To start, Frank led a steep slab with a grassy crack up the middle with the help of his Chouinard Alpine Hammer Pick placed firmly in the sod crux. A very stinky dead marmot nearly forced a retreat but we solved the problem when Frank grabbed it and tossed it off the North Face. Mike danced up the aid pitch free. I followed and cleaned while Frank happily jumared. Mike and I later agreed it was a 5.9 fist crack. More steep but well-protected leads followed.

All too soon, we were at the overhanging summit block with Fred Beckey’s bolt ladder. I had time to open my pack and get out the ¼” hangers and nuts and strap on the “bolt kit.” About then, a thunderstorm filled the sky and we retreated. It was a close race off the mountain but we beat the storm back to camp.

It appeared that we had hit a storm cycle in an area noted for thunderstorms. The next day started with a thunderstorm but cleared shortly after. It was time to go deal with the tower that I had seen from Fishhook Spire in 1971 and to search a little more for the “Crystal Cave.” We worked our way high up to the west through swollen streams and areas covered with rockfall from recent storms. Then I saw it.

Mike, Frank and I climbed higher and worked our way through route-finding difficulty. The top part of the climb was on unusually choice choss. 2 poorly-protected leads with some 5.9 got us to the summit. Another difficult, obscure but highly insignificant Sawtooth first ascent was mine! Climbing higher, the improbable began to look possible.

From the summit of … wait, this was a first ascent right??? We got to name it. 7 years of searching for this obscure pinnacle. I must have a name worthy of its grandeur. All I could think of was “Bluebonnet.” You won’t find it in any of the Sawtooth guides. I have not shared it publicly until now. But why, you may ask, did we name it Bluebonnet Tower? It just seemed “fun” at the time.

We then took care of the 2nd of 2 mysteries in one day. From the top of “Bluebonnet Tower,” we could see an area of reflected late-afternoon light 1/2 mile south. Could the reflections be from crystals? Within an hour, we were working our way up through an area of large loose rocks and debris. It was obvious that this area had recently broken away from the face above us. We started finding big fragments of quartz crystals.

Then we found what was left of “The Crystal Cave.” It appeared that its roof had broken and fallen, destroying most of the crystals. Some impressive but battered and dirty specimens remained in a dark tunnel that went up steeply. It was a dangerous area. Rocks were falling on us from unstable cliffs above.

It then started raining and lightning was striking higher peaks as we retreated down to camp. That night, the worst thunderstorm of my life hit our corner of the Sawtooths. The lightning bolts worked the surrounding peaks and then started hitting and exploding trees closer and closer to camp. After initial “oh shits” on every close strike, we all burrowed into sleeping bags and dealt with terror, each in our own way. I always preferred whining and shaking as opposed to a previous alternative–moaning and wetting my sleeping bag.

It then started raining and lightning was striking higher peaks as we retreated down to camp. That night, the worst thunderstorm of my life hit our corner of the Sawtooths. The lightning bolts worked the surrounding peaks and then started hitting and exploding trees closer and closer to camp. After initial “oh shits” on every close strike, we all burrowed into sleeping bags and dealt with terror, each in our own way. I always preferred whining and shaking as opposed to a previous alternative–moaning and wetting my sleeping bag.

The wind from the storm hit and started blowing over snags near our camp. Marble-sized hail slammed into us and then a pole broke on our tent. We held together the tent as the hail changed to heavy rain. In between thunderclaps, we could hear massive rockfalls off the surrounding peaks. Finally, the storm departed but we were too wet and scared to sleep well.

After sleeping late into the morning, we dragged our soggy sleeping bags out of the tent and tried to dry ourselves out. There was some minor flooding in camp but we had survived the storm. I was drawn back up to “The Crystal Cave” while Frank and Mike packed up for our hike out. I could not find the cave. Massive rockfalls covered the area that we had looked at the day before. More storm-loosened rock kept crashing down on the same area.

After sleeping late into the morning, we dragged our soggy sleeping bags out of the tent and tried to dry ourselves out. There was some minor flooding in camp but we had survived the storm. I was drawn back up to “The Crystal Cave” while Frank and Mike packed up for our hike out. I could not find the cave. Massive rockfalls covered the area that we had looked at the day before. More storm-loosened rock kept crashing down on the same area.

I finally found one small crystal that somehow survived under a large tottering boulder. It too would soon be smashed when that boulder fell, so I saved it and carried it a short distance away from the landslide. Later I did a solo trip into the same area with minimal gear, wandered around places that were significant to me and then carried the crystal to a safe home.

In 2007, a group of us went into Baron Lakes on a trip we titled “old farts trying to re-create past glories.” Our younger “rope rocket” friend hiked in a few days later. The weather “sucked.” After 36 years, you would think I would know that the weather often “sucks” there.

The “old farts” and Kim. Bluebonnet Tower, Fishhook Spire and Big Baron Spire are in the background.

Chris, Dorita and I tried the original Beckey route on Big Baron Spire and got hit by a snowstorm with a little lightning mixed in.

Chris and Ray posing on the Beckey Route on Big Baron Spire just before the snow hit. Yes, that is a 1973 Vintage Ultimate helmet on me.

We all enjoyed some high mountain exploring between storms. Finally, we “knocked off” a first ascent on an another obscure tower to the east of Baron Lakes with our “rope rocket” Kim leading the way.

Weather for our last full day looked great. Kim wanted to climb a 5.10d crack route on Big Baron Spire. No one wanted to belay and be dragged up but I hiked up there with her and Dorita. Later we hiked rough terrain over to where “The Crystal Cave” had been. Nothing remains but some large broken rocks. Nice view though! Both Kim and I then scrambled up very loose and dangerous rock to a high saddle and an awesome view into Goat Creek and peaks farther west! Danger and scenery at the same time. I still love that adrenaline fix!

“The Crystal Cave” is buried. The best new routes are all climbed. It is a long hike into the area. Lightning storms are “frequent and vigorous.” A lot of the rock is “choss.” The fish are seldom biting but wood ticks, carnivorous flies and mosquitoes are usually biting. No reason to go there anymore.

I will repeat: collecting mineral specimens has been illegal in the Sawtooths since 1990.