My photographic explanation of why this mountain is called Elephants Perch.

It was love at first sight with me and Idaho’s Sawtooth Range. Rotten rock, mosquito bogs and the annual July plague of biting flies: all failed to dampen my ardor. In 1971, I discovered Elephants Perch. It is a massive dome of beautiful pink granite (Leucocratic quartz monzonite). Its very clean and solid 1,200-foot high West Face is the best big wall in Idaho.

I started technical climbing in the Sawtooth Range in 1970. I was a Ketchum native and my Summer job on a Forest Service fire crew in the area gave me weekends off. Unfortunately, 2 years after a high point in 1971 of 28 days in the Sawtooths, I found gainful employment running an outdoor store in Moscow, Idaho. After that, my time in the Sawtooths became the typical “long-distance” love affair, with short visits throughout the 1970s and early 1980s.

In 1971, I learned that Fred Beckey (renowned Seattle Mountaineer) had done a Grade V route on Elephants Perch. Rumor had it that a convenient belay ledge capped each 150-foot lead. While climbing in the area in 1973, I spotted a line of weakness on Elephants Perch that I assumed was “The Beckey Route.” It took me 2 years to find the right partner for the route. Before the mid-1970s, there was no Sawtooth Range guidebook. Other than an occasional note in climbing journals, climbing history in the Sawtooth Range was all word of mouth.

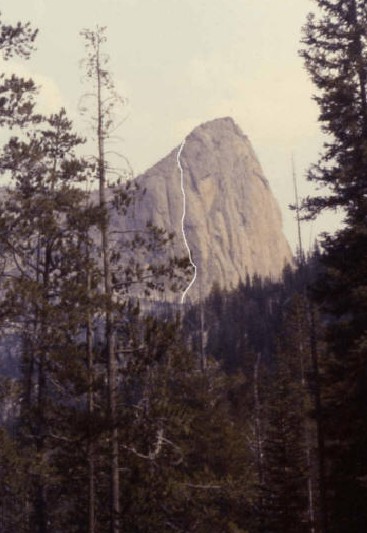

The West Face of Elephants Perch as viewed from Goat Perch. The Pacydermial Pleasantries Route is in white.

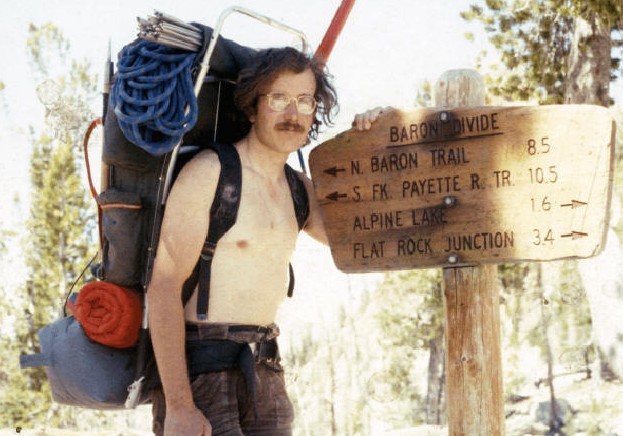

In the Summer of 1975, Chris Puchner and I decided to climb Fred Beckey’s route on Elephants Perch. Day One: we lugged large packs full of big wall climbing gear into the lakes at the base of the wall. To carry both climbing and camping gear, each of us carried two packs lashed together. These masochistic bundles of equipment exceeded 70 pounds each and had been dubbed “Sawtooth Overloads.”

At that point in my life (age 25), I had climbed one Grade V direct aid route: Leaning Tower in Yosemite. My chief background in direct aid was occasional use of it on an otherwise free climb. Chris Puchner had done a small amount of aid climbing, but he was a natural athlete and always game for anything that entailed suffering.

Following what we thought was Fred Beckey’s classic line, we proceeded for 7 slow leads up a suspiciously easy route, just north of the center of Elephants Perch’s massive face. In current terms, we were in the first major-crack system to the north of “The Mountaineer’s Route.” We mostly free climbed but, on our last pitch, Chris ended up doing some direct aid as well. At the end of Lead #7 was a nice, flat 10 x 10 ledge waiting below a slightly overhanging, very thin crack. Since we had brought bivouac gear, Chris and I decided to wait for morning before attacking the wall above.

During the short night, a cloud of mosquitoes raised unseen from the lakes below and, in our sleep, we were both savagely attacked. I remember Chris mocking my puffy face the next morning. However bug bites on a bivy were much better than a thunderstorm–always our major fear in the Sawtooths.

The next morning we discussed our growing certainty that we were on unclimbed terrain. We felt excitement about pioneering a new route, rather than depression at not being on “The Beckey Route.” We always enjoyed doing something different. Thus inspired, but stiff and bug bitten, Chris attacked the aid crack above our ledge. The crack ran vertical about 20 feet to a small overhang, then continued thin, vertical, and unrelenting for a full 150 feet to where the crack finally widened. Chris went up a ways, bitched about not having enough thin pitons and retreated. I accepted his judgment and we rappelled off the route.

In the Summer of 1977, I was back with a secret weapon and a fantasy. The secret weapon was Mike Paine, a very good climber who I suspected would be of great help in climbing Elephants Perch. I had also found more information on Elephants Perch and was certain that instead of repeating the Beckey route, Chris Puchner and I had stumbled upon an actual new route.

The plan was to do the route with Mike and my girlfriend Jennifer Jones, just before my 10th high school reunion in nearby Hailey. Ray Brooks (high school social retard and non-athlete, voted most likely to be a nuclear physicist) would show up for the class reunion having just knocked off a prestigious first ascent in the Sawtooth Range. I would, of course, have my tanned and muscular woman on my tanned, muscular, and hopefully slightly scarred-up arm.

Once again we had to haul a huge load of climbing gear to the base of Elephants Perch. However, we had stashed 3 climbing packs full of food and climbing gear at the entrance to the canyon that goes up steeply to Elephants Perch on another climbing trip into the Sawtooths a few days before.

Unfortunately, when we arrived at the place where I had hidden the packs under bark and vegetation, they were no longer there. Some searching revealed fresh bear scat with aluminum foil in it. A wider search revealed 2 destroyed packs, no food and some climbing gear scattered around. Finally we found the 3rd missing pack over 200 yards away. It had been full of only climbing gear, weighed about 30 pounds and was intact but covered with tooth marks. United with our gear, we were short of food and low on water containers, but had enough equipment to proceed.

Mike Paine and I had been climbing together a lot that Summer. But Jennifer had not climbed at all since she had been off on an archaeological dig in Washington. We humped our “Sawtooth Overloads” up the steep climbers trail from Redfish Lake Creek into Elephants Perch Valley. Then Jennifer and I spent the late afternoon on a short warm-up climb for her.

Early the next morning we were off and up, burdened with bivouac gear and water for a 2-day climb. Mike and I swapped leads, making rapid progress up the first pitches, which had taken Chris Puchner and me a whole day 2 years before. Early in the day, we unexpectedly found ourselves back on the fine flat bivouac ledge, just below Chris and Ray’s high point of 1975. We had turned the 7 leads into 5 leads with my knowledge of the route and Mike’s willingness to run out the rope. Mike had also free climbed through an area where Chris had resorted to much slower aid climbing. Directly above us in a right facing corner stretched the thin aid crack.

As the direct aid expert or, more correctly, as the only person with much direct aid climbing experience, I got to lead the long, thin, aid crack. I had brought every thin piton and nut available for the aid crack and I used them all. The small overhang was not difficult to aid over but above that the crack stayed unrelentingly thin, accepting only Knife Blades and thin Lost Arrow pitons. It finally started to widen just as I was running out of thin pitons. I must confess that my lack of aid climbing experience and the vertical wall kept me placing aid pitons more closely together than good style dictates. The “clean climbing-throw away your pitons and use nuts for protection” revolution had occurred in the early 1970s. We were fervent users of nuts, when possible. In this crack, however, it was mostly not possible.

Somewhere well up the aid crack, I ran so low on thin pitons I was forced to resort to very small wired-nuts (Copperheads) for aid placements. Some of these did not exactly fit well into the skinny crack so I resorted to bashing them into place while nervously humming that old British ditty: “When is a chock a peg?”

One well known fear of aid climbers is the dreaded “zipper” fall: where an aid placement you are standing on fails, then a number of placements below fail when your accelerating falling mass “zips” them out of the crack. I was aware that below me were a bunch of fairly insubstantial nuts and pitons. Of course, one of the nuts I had hammered on popped out of the crack just after I fully committed my weight to it. Thankfully, my “zipper” fall only pulled 2 more pieces of aid out of the crack before the rope stopped me.

I was used to taking lead falls but generally there was nut protection I trusted in cracks below me. Here the little demons inside my head were chuckling loudly about my good chance of taking a huge fall when every thin piton below me zippered. I pushed my fear into action and renewed a controlled struggle back up the crack. At almost the end of the 150-foot rope the crack widened slightly and accepted several large nuts. I felt relatively safe.

WOOHOO! I had a decent semi-hanging belay with even a slight footrest. I had vanquished the thin, vertical aid crack. Mike Paine jumared up the rope to me, shared some water that I was very grateful for and attacked the next lead. Above my belay, the crack was wider and in a much larger right-facing corner. Mike was forced to aid climb up the crack, and suffered considerably. There were 2 problems. First, although Mike was a great free climber, he had done very little direct aid climbing. Second, the suddenly wide crack demanded large nuts which we did not have a copious supply of.

I had convinced myself the worst was over after my lead but Mike’s thrashing and muttering above me indicated otherwise. However, I knew that even if Mike ran out of nuts for the crack, we had brought along “the bolt kit.” This consisted of a ¼-inch drill in a steel holder and a small supply of bolts. When a climber could not find anywhere to place a nut or piton, he could always spend 20 laborious minutes hand-drilling a 1½-inch deep hole by hammering on the drill then pound a special “Rawl” drive-in bolt into place. Although this was accepted technology for rock climbing, it was considered to be “bad form.” In theory and practice, climbers could climb almost anything by “bolting their way up.”

A possible slide into the low morals of using bolts for upward progress was taken out of our hands. During Mike’s struggles, the drill and holder (which had been in his pant’s pocket) worked loose. I heard a melodic “ding, ding, ding” and muttered “oh shit.” The bolt kit came flashing by me. We were now limited to cracks for placing our protection.

After more struggles, Mike finally called down to me that he was giving up on the crack he was in. He wanted me to lower him from a secure nut he had placed at his high point and he would pendulum to another crack about 20 feet to our right. This was a fairly normal maneuver in big-wall climbing. I started lowering Mike back down to my belay point to make the pendulum. However, when he was about 15 feet above me he started rolling his eyes and groaning.

Mike Paine had a mild form of epilepsy from a high school football injury. I had seen him have seizures twice before and the symptoms he was exhibiting now were identical to those starting a seizure. I knew he would instantly be fine if he could take his medication pill, which he always kept handy. I feared he might not be able to access those pills without my help. The consequences could be horrible.

I dropped Mike to my belay quite quickly. At that point, he looked at me with alarm (as he was bouncing up and down) and exclaimed: “Christ, Brooks, what are you doing? The nut I’m dangling from isn’t that solid.” I quietly asked, “You’re not having a seizure?” “No way man,” Mike replied, “The climbing harness was just killing my kidneys.” So with that crises over, Mike was able to run back and forth on vertical rock, supported by the rope, and grab onto the crack 20 or so feet to our right. He scrambled up some lower-angled rock a few feet, put some nuts in for a belay and I thought we were all set to go higher.

The maneuvers I would have to perform to follow Mike’s pendulum were a little complicated and put me at risk of a considerable fall onto Mike’s belay. For that reason, I asked Mike to reassure me that he had a good belay just in case something went wrong. He wouldn’t give me any mental comfort. I just wanted him to tell me it was okay. We proceeded to have a fairly loud discussion on the subject that ended with him shouting: “Christ, Brooks!” “When is a belay ever really good!” At this point, we decided to call it a day and retreat to our bivouac ledge 150 or so feet below.

By this point, Jennifer had been waiting patiently on the bivy ledge for about 6 hours. She had been alarmed by increasingly urgent yells between Mike and me and had, early on, noted the passing of our bolt kit. Somewhere in that long stressful afternoon, she decided it looked a lot like Ray and Mike might well go ding, ding, dinging, down the wall just like the bolt kit. After that epiphany, she prudently untied from the potential mutual suicide pact that she suspected the climb had become. Securely tied to her ledge, but not to us, Jennifer had somewhat tearfully waited for the drama to play out.

I should mention that in a 30-year climbing history, I have only witnessed one other incident where a climbing party member had decided to unrope before a possibly deadly group fall could occur. I was climbing in the Canadian Bugaboos in the mid-1970s with Chris Puchner. We impressed a couple of very competent female climbers with our ice climbing abilities. They subsequently dumped the English lads they were climbing with and went off to the Canadian Rockies to climb with us. Climbing conditions were horrible due to recent heavy snow. In desperation, we ended up doing the tourist route on 11,100-foot Mount Victoria, which had enough fresh snow to make it “very interesting.”

On the descent from the summit of Mount Victoria, I belayed my female climbing companion down a steep, but very snowy, chimney. She exited onto a ledge and vanished from my sight. After a few minutes, she called “On Belay.” I climbed and skidded down the mixture of loose rock and snow in the chimney without ever finding a substantial hold. Several times I believed I was about to fall, but knew the rope to my partner would catch me. After a while, I reached the ledge and walked around a corner to see her tying back into the climbing rope. She looked up and saw me, then quite calmly said: “I couldn’t find any anchors to protect a belay with. Didn’t see any reason to die with you if you fell.” Women are so practical!

Once Mike and Ray rejoined Jennifer safely on the bivouac ledge, all was soon better. A little food and water led to a good night’s sleep. No mosquitoes or thunderstorms arrived during the night and the next morning we woke ready to continue the climb. Mike and I jumared back up to my high point. Mike cleaned the nuts from his pendulum lead, protected by my good belay anchors and then jumared up to his doubtful belay. With more nuts, he was able to improve the anchors and pronounced it “pretty good.” Of course, if we hadn’t dropped the bolt kit, we could have set “bomb-proof” belay anchors with it. I then jumared up to Mike’s belay while Jennifer took up my old belay station as a safety backup.

At that point, Mike took off on the most difficult free-climbing lead of the route. It involved a delicate balance of friction and crack climbing on a very steep slab. Mike thought it was 5.9 and after following the lead with jumars, I was willing to agree. My next lead took me into a huge lower-angled chimney. When I reached the end of the rope, I propped myself into the chimney, placed anchors very carefully and then belayed up my partners. The problem was that the back of the chimney (about 5 feet below my belay) was piled with loose rock. If our climbing ropes disturbed any loose rock, those below me would not have enjoyed the subsequent projectile shower.

As I belayed up Mike and Jennifer, I coiled the rope over my legs to avoid disturbing rocks. Mike led on up, Jennifer went next and, about 1-½ hours after propping myself across the chimney, I could finally move. I immediately discovered a problem. My left leg had gone to sleep. It was numb from the knee down.

After doing all the standard things you do to wake up a numb limb, I gradually accepted I had a problem. The leg worked; I just couldn’t feel anything with it. I climbed up to Mike and Jennifer and informed them I had a slight incapacity. Mike led the final 3 easier leads and we were on top of Elephants Perch at about 1:00PM. We loitered around the summit for a while then decided that, if we were going to make my class reunion party, we had better start down.

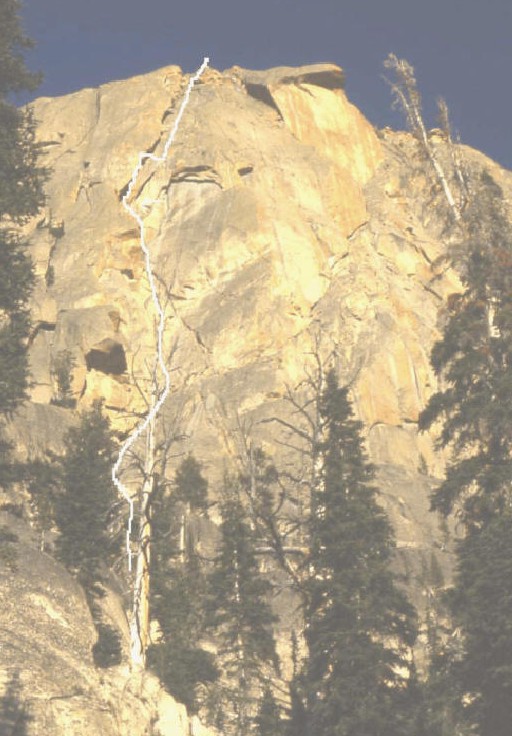

The Pacydermial Pleasantries Route is in white. The arrow shows the bivouac ledge. The job to the right with white line indicates the pendulum.

Since my leg still had not awakened, Mike and Jennifer took most of the weight for the climb down. The easiest routes off of Elephants Perch are mostly walking down talus. I soon discovered I had to pay very careful attention to foot placement with my left leg, otherwise it would buckle under my weight. Despite my care, I took a couple of minor falls.

After reaching our camp, we jumped in the lake for a much-needed bath. Cleaner and much revitalized, we set off down the steep trail to Redfish Lake Creek. We had also picked up our backpacks and camping gear and now had more weight. Mike had martyred himself carrying a huge amount of weight, but I had about 50-60 pounds of gear in my Kelty frame backpack. Of course, my leg was still numb. The mile or so down to Redfish Lake Creek is very steep and I had to be very careful. I took more minor falls along the way.

Finally, we hit the creek bottom and some smooth granite slabs for walking surface. In the dim forest light of early evening, I failed to see a small stick that rolled under my right foot. I lost my balance and quickly threw my left foot out to catch myself. My left leg collapsed (it was numb, you remember) and I found myself stumbling faster down an inclined slab with the heavy backpack and gravity forcing my upper body head-first toward the granite.

About 2 inches before I slammed head-first into the granite, the frame extension on my pack hit the slab first. I somersaulted over into a sitting position and screamed: “That’s it!!” I think my bulging eyes nearly touched the rock just before the frame extension hit! I had been acutely aware my skull was about to be shattered like a ripe kumquat!! It was not in my stock of outdoor trivia that a pack frame extension could also function as a “roll bar.”

The pack with “roll bar” that saved my head. The red item is a fishing rod.

There was still a delicate log to walk over Redfish Lake Creek then 2 downhill trail miles to the lake and hopefully a waiting motorboat. After we reached the far end of the lake, we would have had a 65-mile drive to Hailey and the party. We camped right where I had fallen instead. Yes, I gave up on making the class reunion party. They probably would not have been impressed with our smelly bodies and matted hair. I didn’t have any good scars on my arms either.

The next morning, we cleaned up the remains of the picnic the bear had made of the two stashed climbing packs a few days before and had a mellow walk out. My leg recovered in about 6 months. I made it to my 20th class reunion. One disappointment was that we only took one picture the 2nd day of our climb. I have discovered that the number of pictures taken is inversely proportional to the difficulty of the route. Somehow the camera never got much use when I was suffering through an epic. I think it all has to do with priorities. For us, staying alive was more important than taking pictures.

I wrote up the route as “Pacydermial Pleasantries” for the American Alpine Journal. They published the description, but not my cool route name. I indignantly protested: since I had achieved a pinnacle of status in the climbing community with a free charter membership in the DFC&FC as well as a paid membership in the American Alpine Club. My protest was ignored. The rumor mill told me the stuffy AAJ editor only allowed route names that were in Webster’s Dictionary or were proper nouns. “Pacydermial” was not in Webster’s and did not make the cut.

Ray Brooks

Copyright 2003

Below is my heavily edited (by AAJ staff) route description. They even changed my first name from Ray to Raymond.

The 1979 American Alpine Journal route description under “Climbs & Expeditions: Idaho”:

Elephants Perch, Northwest Face, Sawtooth Range. Chris Puchner and I attempted a new route on the Northwest Face of Elephants Perch in 1975 but ran out of thin-crack aid gear. In 1977, Mike Paine, Jennifer Jones and I completed the 11-lead route in 2 days. The route is 150 to 200 feet south of the route Bill March did (A.A.J., 1976, Page 455). Our route went up the right side of a huge flake while he went up the left side of it. Raymond Brooks