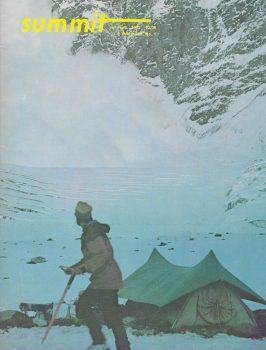

SUMMIT, January/February 1983, Volume 29, No. 1

I read recently about a climber who was tracked down and captured by Canadian Airborne Park Rangers. What was his crime? The climber was attempting a solo climb of Mount Saint Elias. This event on the Canadian mountain has moved the classic conflict between freedom and regulations into a realm that could be better understood by reading George Orwell’s 1984 than by reading the works of John Muir. Regulations covering mountain climbing in the U.S. are burdensome and are often not essential.

A climber once told me, “We have government bureaucracies to match the largest mountains and enough regulations to equal all known climbing routes.” This may be an exaggeration, but there is a worldwide trend to regulate the sport of climbing. Mount Everest has always been regulated and is now enclosed inside a National Park.

The National Park idea itself confuses the issue. Regulations are justified by linking them with preservation of the environment, preservation being the mission of a National Park. Mountaineers want their climbing areas protected and preserved. However, many of these same mountaineers find that there are many regulations which have little effect on preservation of the peaks. This regulated loss of freedom makes climbing more difficult. Perhaps freedom and preservation are such conflicting needs that they cannot be compromised. The question, therefore, involves what regulations are needed for protection of the parks and what regulations are not needed for protection of the parks.

Wyoming is a wonderful place for mountain climbing. Within the state’s borders, there are a lifetime of climbing opportunities for even the most prolific climber. Two large and famous peaks in the state provide not only superb climbing opportunities, but also an example of contrasting management philosophies.

Tale Number One

A cold wind was blowing and snowflakes were stinging my face. A storm was building to the west. My wife and I were sitting on the summit of Gannett Peak, the highest point in Wyoming. “Are you going to wear crampons on the descent?” “No.” “I am,” I said, shivering. “If this storm settles in, the snow could freeze up in no time.”

“Yeah!” Dana answered, less than enthusiastically. The most vivid memory of our climb that day had been of putting on and taking off our crampons. Hard snow, soft snow, ice and rock. Every time conditions changed, we adapted. Our personal safety had been uppermost in our minds. “The guy in the waffle stompers didn’t seem to be worried about ice,” Dana said. “No,” I answered as I thought about a climber who had fallen the week before in the Tetons. “No, the guy in the funny shoes wasn’t worried,” I mumbled as I became preoccupied by a startling vision that was appearing before me.

We were 7-1/2 hours from our base camp in lower Titcomb Basin. The base camp itself was 20 miles from the trailhead. Our climb had started at 5:30AM with a dark hike along Titcomb Lakes. We had cramponed up and then down Dinwoody Pass, crossed the Dinwoody and Grasshopper Glaciers, jumped crevasses and inched across snow bridges. We carried with us a rope, prusik slings, crampons, ice axes, extra clothes, food and a climbing guidebook. We were prepared.

Now, less than 50 yards away, I saw a man and a dog. They were trudging up the last little slope to the summit. Dana spotted the pair and pointed to them. I then realized that what I saw was no illusion. A few minutes later, the climbing team arrived on the summit. The man was dressed in gym shorts, a t-shirt and hiking boots and had a sweater tied around his waist. The dog (a small German Shepherd) had no collar.

“I told him to stay in camp but he never listens to me,” the man explained. “Does he do many peaks?” “He stays off routes over 5.4.” “That’s good for a dog,” I said. “He’s getting old,” the man said, as he gave me a look that seemed to me to be saying, who are you calling a dog? “I didn’t think a dog could make it up here.” “I didn’t see any signs,” the man said and the dog barked. Feeling slightly deflated, we left the summit.

Tale Number Two

The sun was setting in the west and, to the east, the long triangular shadow of the Tetons was spreading across the valley floor of Jackson Hole. Camped out on the Lower Saddle, which stretches between the Grand and Middle Tetons, was an odd collection of mountaineers. The term mountaineers is used in a general sense for this group. A wide range of climbing abilities and degrees of commitment were represented by the group. There was a climbing guide who had done more Grade VI climbs than anybody and a 72-year-old man accompanied by 2 other guides. Most of us fit somewhere in between. A metal hut owned by the guide service and an open air vault toilet supplied by the Park Service were surrounded by numerous tents and rock shelters.

The sky was clear and the weather was perfect. At this late hour, climbers were still returning from their Grand Teton climb. The climbers on the saddle sat around their tents, eating, discussing tomorrow’s climb or perhaps contemplating use of the public toilet. As the light faded, I noticed a big man with an even bigger pack walking up the slope toward our tent. “Hi,” he said, with a thick Australian accent. We nodded hello.

“Where are the good campsites?” “This is a nice one,” I said, amused with myself. “I think all of the good sites are taken,” Dana said. “I have a permit,” the Australian stammered. Dana and I looked at each other and we passed winks. “Maybe you should find a ranger.” “Is one around?” he asked. We couldn’t answer that question. We hadn’t seen any uniformed personnel, but we always felt like there might possibly be an undercover ranger around posing as a hapless climber, or maybe inside a dome tent and just waiting to spring on some unsuspecting climber. Perhaps the perpetrator would be a climber who had overstayed his permit while waiting out a storm. or who had wandered off the route designated on his climbing permit. I even wondered if maybe this Australian might not be a closet Serpico snooping out a big bust.

The Australian took off his pack and looked back down the trail. “My mates ought to be here soon. Are you climbing tomorrow?” he asked. “Yes.” “Exum route?” he asked and then continued without waiting for a reply. “The Exum, the classic route.” He looked up at the now dark peak and struck a classic pose. “I wish they would outlaw the Owen-Spaulding Route.” “Why?” “The route is grungy; it isn’t climbing. If you can’t climb the Exum, you shouldn’t be climbing. A regulation is needed to protect the mountain for real climbers.” At this point, we excused ourselves and retired into our tent to sleep and to worry about being arrested the next day for climbing a grungy route, a climb most foul!

It’s the Law

Gannett Peak is under the jurisdiction of the National Forest Service and is located inside a designated Wilderness Area. The Forest Service is a federal bureaucracy dedicated to the multiple use of its lands. Climbing is 99% unregulated. You can climb Gannett Peak in tennis shoes and a kimona if you want, and you can take your dog if you choose. The Grand Teton is “operated” in an almost Disneyland fashion by the National Park Service. The National Park Service is another governmental creation dedicated to the preservation of its lands. Climbing is regulated, directed, guided, and often stimulated by the Park Service bureaucracy.

While, to the best of my knowledge, the Owen-Spaulding route on the Grand Teton has not been regulated out of existence by the Code of Federal Regulations, climbing is definitely regulated. On our climb of the Grand, we met no dogs and no unprepared climbers. Climbing parties were tagged with permits and bivouacked in “designated” locations. Most climbers were serious, dedicated and often a little apprehensive about their goals.

On Gannett Peak, in contrast, there were fewer climbers and due to the absence of regulations, climbers were free to be themselves–individuals. The Park Service and the Forest Service have 2 different approaches to land and people management. Both agencies management philosophies are successful to a certain extent, or at least serve their purposes. Are extensive regulations administering climbing necessary? The question has become irrelevant because regulations like their parent bureaucracies are a reality. The important question always will be what type and how much regulation is necessary?

To answer the regulation question may not be difficult, but to implement significant changes may be impossible. In the Canadian episode that I mentioned earlier, the minimum climbing party must be 4. A party of 4 is seen as being better able to self-rescue itself and, therefore, save the money involved in expensive helicopter rescue efforts. Evidently, more money was available for law enforcement than for rescuing human beings. Shouldn’t this be considered misguided priorities that are counterproductive to the overall goal of the regulations–the goal being the promotion of safe climbing?

The safety issue itself is a controversial one that can be deregulated. You cannot regulate safety. Despite the regulations and efforts of the National Park Service, people still die every year in the Tetons. In fact, the regulations designed to promote safety may induce a false sense of security that may encourage unqualified climbers to “try” the Tetons. Safety, in the end, is an idea a person either has or does not have.

Due to an ever-increasing population, the temptation to use regulations to protect climbing areas will continue to be a serious problem. In developing or reviewing regulations, rangers, and bureaucrats should work together to make regulations meaningful. Unnecessary regulations should be eliminated, and regulations should only be used to reconcile conflicts between needs which cannot be compromised.

Next: The City of Rock