Mount Breitenbach, at 12,140 feet is Idaho’s fifth-highest summit and is located in the Lost River Range in Central Idaho. Thanks to the efforts of the Idaho climbing pioneer Lyman Dye, Mount Breitenbach was named for John Edgar (Jake) Breitenbach. Breitenbach was killed by a collapsing ice wall in the Khumbu Ice Fall on March 23, 1963 while climbing with the American Everest Expedition. Lyman, who learned his mountaineering skills from Jake in the Tetons in the early 60s, successfully petitioned the Governor of Idaho and the USGS to officially adopt the name.

The East Fork of the Pahsimeroi River drainage. Mt Breitenbach is the distant peak, right center. Bob Boyles Photo

During the spring of 1983 my climbing partner Curt Olson called me and Mike Weber with an idea for a new climb in the Lost River Range. A few years earlier Curt had attended a lecture at Sawtooth Mountaineering in Boise where the legendary British climber Bill March gave a talk and slide show. Bill was a highly accomplished climber and educator who moved with his wife from London to Pocatello to run the Outdoor Program at Idaho State University. The very last slide in the long presentation showed the North Face of Mount Breitenbach. Bill had been on it twice with ISU students and ran into a headwall that he said would require big wall techniques and bolts to finish due to very severe rock climbing at the top of a large snow filled couloir (gully). Curt, Mike and I were veterans of a number of routes on the North Face of Mount Borah so the idea of doing a first ascent in the range didn’t take much convincing for any of us. Curt got us all excited about the climb and we agreed to go but a little snag showed up that almost sunk our plans: Mike and I both refused to take our cars in there again. Curt didn’t own anything that would make the rough drive into the East Fork of the Pahsimeroi so we were at an impasse. A few days later Curt came up with a solution. Curt was teaching climbing and taking out backpacking groups for Boise City Recreation at the time. He convinced Segal Branson, the head of City Rec to let him use a van to recon for possible future City Rec trips (wink, wink). The adventure was on so we picked our dates and cleared our schedules for the trip to come.

On the day of our departure we loaded up the van and drove from Boise to Arco and then north on Highway 93 to just past the Mt. Borah turnoff where the Doublespring road takes off. The Doublespring road is rated as an “improved” dirt road but those not familiar with Idaho road ratings might question this. Unless Doublespring has been recently graded, it’s a long, dusty, tooth-rattling drive on what is known as washboard. After tenmiles and an 8,300 foot pass, the road becomes more interesting when it turns to unimproved on the way to Cayuse Canyon and Horseheaven Pass.Around seven miles further, the road turns to “primitive,” which is kind of an understatement. This so-called road was made by four-wheel drive vehicles and hasn’t seen the blade of a grader since it was punched in. I was on this road thirty years after our trip and can only describe it as being in worse condition due to the wear and tear of tires exposing the rocks in the path.

When we got to Mahogany Creek in the afternoon the water was flowing quite high so we stopped to inspect it before Curt tried to drive the City Rec van through. Mike and I waded across the creek. It was just about to our knees so we decided not to get back in the van until Curt drove through. I told Curt the Idaho saying I had heard while learning to drive big trucks: “never say whoa in a mud hole.” He punched it and kind of nosedived in off the steep approach. When he got about halfway across,the current hit the side of the van and it briefly went up on two wheels. For an instant Mike and I thought it was going to roll over in the creek, but luckily it didn’t, and Curt plowed through to the other side. I remember the van leaving a wake in the creek like a boat on water. Once across, weloaded back into the van but still had Rock Creek to drive though before we reached the confluence of the East and West forks of the Pahsimeroi River. Rock Creek was flowing high as well, but it’s a shorter crossing. After one quick look we splashed through without an incident. After a few more miles of rough road we came to the confluence of the East and West forks where we took a left at the junction and drove until the road became so bad that walking was a better alternative to driving. We parked the van and loaded up our gear for the four-mile bushwhack up the river to the base of the North Face.

It was late afternoon when we found a nice camping spot near the top of the timberline for our tent and overnight stay before our climb the next morning. Besides the usual gear like tent, sleeping bags, stove, food etc. we had ropes, ice axes, crampons and rock and ice anchors, along with all the other climbing gear that might be necessary for a mixed (snow and rock) climb. Fifty pounds and up was not an unusual load for any of us. It’s typical to feel a sensation of floating after carrying a pack that’s heavily loaded with both camping and climbing gear. This time was no exception.

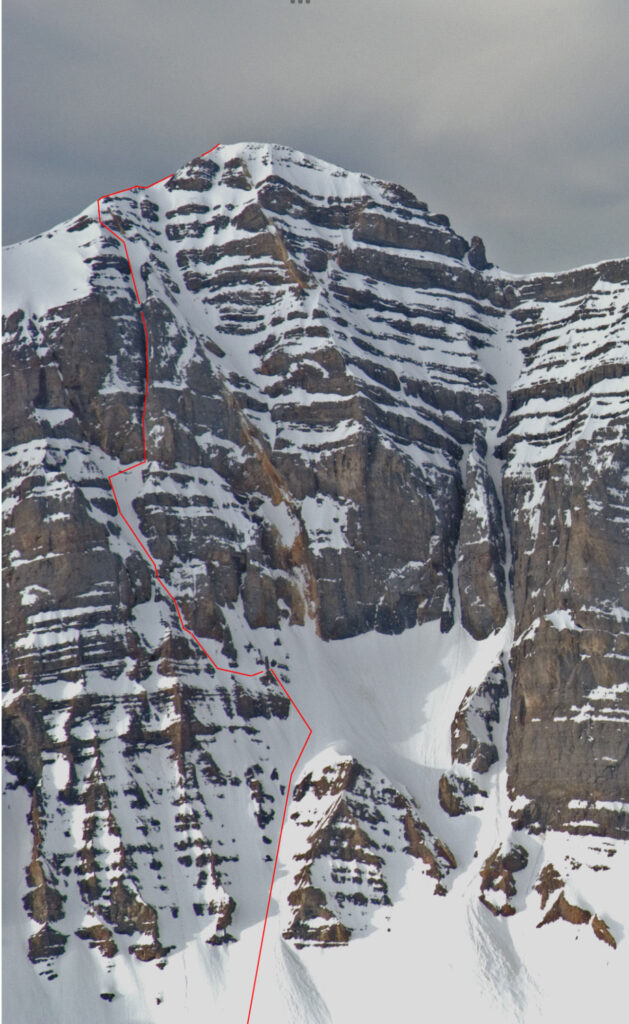

With the long July days, we had plenty of time to set up our camp, eat and make a preliminary inspection of the route that we planned to climb the next day. We easily identified the couloir and rock band that Bill had attempted and also discovered a possible route to the west of that couloir but still east of the summit. There were two features on our proposed route that stood out. The first looked like an overhanging section of rock below the final couloir, and the second, a large rock, or chockstone that blocked the exit near the top of the couloir.

I remember that our attitudes were pretty casual all evening and we stayed up quite late telling stories about our past climbing adventures before we turned in for the night. Normally we would opt for an alpine start (like the middle of the night) for a big, unknown climb like we were facing. This time our casual attitude continued through the next morning when we ate a leisurely breakfast and poked around until around 8:00 AM before we loaded up for the climb.

The approach started out on scree but soon turned to snow, which we’d be on for most of our climb. The beginning was moderate in steepness but once we got above the moraine the angle reared up sharply. We climbed the first snow slope without ropes or protection but when we came to a large limestone stack it was time to get serious. We had to make about a two-rope length horizontal traverse to where the steep snow ran out above rock bands. A slip at this point would have led to a quick slide and crash on the rock bands below.

Mike and the author at the limestone stack.

Surprisingly, this feature survived the 1983 earthquake that occurred later that October. Curt Olson Photo

We took a short break at the stack and setup anchors for the roped traverse across the face to the next hanging snow field. From this point on we moved one-at-a-time, with the leader going first and then the second and third following in sequence. The next snow field led to a section of steep, bare rock so we put away our ice axes and switched to rock climbing mode. With few holds and no real cracks, this section of rock proved to be the hardest free climbing we found on the route. Luckily for us, the steepest rock on the face was quite solid where some of the lower angled rock was more like compressed dirt. Curt led this section, which ended at a small, sloping ledge just big enough for two.

I came up second and when I reached the ledge where Curt had setup the anchors my first thought was, “This looks pretty sketchy.” Curt had strung about five or six tiny pieces of gear together with slings to make an equal tension anchor where if one piece failed the load would transfer to the next piece and so on. My next thought was, “This anchor system looks like a Rube Goldberg contraption and I sure hope I don’t have to test it.” I didn’t say anything and tied into the anchors so I could bring Mike up.

Once all three of us were on the sloping ledge and anchored we took another short break before we pulled out our ice axes to climb the ever-steepening snow field above. I took the lead on this section staying close to the rock where I could find something to anchor to before bringing Curt and Mike up. From my vantage point I could finally see the section of steep, bare rock that we’d spotted the day before. It was a short, overhanging, dry waterfall maybe 40 or 50 feet in height, that blocked the entrance to the final couloir. I was a bit concerned. If we couldn’t get up this feature, retreat at this point would be very undesirable. We were over 2000 feet up the mountain and it was getting late in the afternoon. I led the traverse over to the base of the rock and then brought Curt and Mike over. Luck was with us one more time: Upon a closer inspection we could see just enough features to make climbing this obstacle possible. Curt took the lead on this section and used aid (climbing on gear) to get up the overhang. Mike went up second as I waited for my turn. Mike had cleaned all of the gear that Curt used to climb the overhang and I used a pair of ascenders (Jumars) to climb the free hanging rope. I was up against the lower angled rock at first and could use my feet to keep stable but when I went higher I was hanging free on the rope. The rope had a few twists in it and I started to slowly spin around in circles. For a few seconds I was face into the rock and for then for a few seconds I was looking down some 2000 feet to the base of the mountain. The perspective was something I will never forget.

As I pulled over the lip of the overhang I could see Curt and Mike some ten feet back in almost a cave-like feature. We were at the bottom of the final snow couloir but could still not see the chockstone because of the steep snow accumulated in the bottom of the couloir. I took the lead and climbed what was the steepest snow we had encountered until I could finally see up the rest of the route. It was a great relief when I saw that the rock was wedged above the snow on both sides of the gully leaving just enough room to climb under it. I yelled down, “It goes.” So, facing no more big obstacles, all three of us climbed the couloir at the same time. Some 900 feet later the angle let up and we could see the top of Mt. Breitenbach to our west. We topped out on the ridge and then realized that our casual start was coming back and bite us as the sun was setting over the mountain in the west.

Our plan had been to descend the North East Ridge but it was unknown territory to all of us. We traversed the ridge as far as practical until darkness set in, then used the last bit of light to prepare a bivouac spot where we’d spend the night. We didn’t have sleeping bags or pads so we moved as many rocks as we could to level out a spot on the ridge and put our packs and ropes down for padding. The sky was overcast so the night wasn’t too unbearable above 11,000 feet but the lightning in the distant mountain range was of some concern. Fortunately, the storms stayed away all night. After two days of hard work and a bit of tossing and turning we all slept soundly. At first light in the morning, having learned our casualness lesson, we were eager to get off the mountain. We packed up our gear and continued down the Northeast Ridge where we ran into a few more technical difficulties before we could get off the face to easier ground. The long drive out was slow and not nearly as exciting the creek crossings being at their morning low flow.When we got back to Boise, Curt retuned the city rec van, unharmed except for a bit of dirt and wear-and-tear.

The North Face of Mt Breitenbach with our route shown in red.

The limestone stack is clearly visible in the lower third of the photo. Wes Collins Photo