ARTICLE INDEX

The Summer of 1972 was hot and humid in Coldwater, Michigan. After returning from the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, I started work in the maintenance department at the Federal Mogul warehouse in Coldwater. The job was okay but my heart was not in it. My thoughts were constantly on heading to the West once again.

Studying maps and reading about possible destinations, a plan began to coalesce in my mind. I calculated how long I would have to work to cover both a trip and my expenses for the school year. Fortunately, the Union at Federal Mogul had forced management to pay Summer help the same starting wage as Union members and I was actually making money. I concluded that if I quit on August 1st, I would have enough money and nearly four weeks to travel.

I bought a train ticket from Chicago to Flagstaff, Arizona before I broke the news to my parents. My mom was supportive and offered to drive me to Chicago. I had 3 definite stops on my itinerary. The first was the Grand Canyon. The second was Mount Whitney in California. The third was Idaho Falls, Idaho. Just before I left, I got a letter from my prodigal friend Doug inviting me to meet up with him when he finished the University of Michigan Geology Summer Camp Program south of Jackson Hole.

Does Your Mamma Know?

The train reached Flagstaff at 3:30PM on a Friday afternoon. I grabbed my pack and headed for the highway to the Grand Canyon. I put my thumb out. Almost immediately, a pickup truck stopped. Inside, two Navajos looked at me. “Where you going?” I told them the Grand Canyon. “Get in. We’ll take you most of the way.”

I threw my backpack in the back and got in the cab. The one sitting in the middle handed me a pint of whiskey and said, “Drink up, its a long drive.” After each of us had taken a swig, we exchanged names. They told me that they worked for the railroad and were heading home for the weekend. After learning of my planned itinerary, the driver asked “Michigan” (his name for me), “Does your mamma know you are out here to sleep with the grizzly bear and rattlesnake?”

I wasn’t sure if it was a rhetorical question or if he really wanted to know. The conversation continued in this vein for many miles. The driver was intent upon determining my fitness for sleeping with grizzly bears and rattlesnakes. His friend kept passing the pint. About 50 miles from Flagstaff with the pint empty, they pulled into a trading post with a restaurant and a bar on the west side of the road and a motel on the east side. A very tall Navajo in full cowboy attire was leaning against a post in front of us. Another pint materialized and I was offered another drink. I was getting quite drunk. I wondered how long we were going to sit there. Another Navajo (this one very short) came out the bar door. The driver said, “Michigan, watch this.”

The newly-arrived Navajo walked up to the tall one. He asked for money. The tall one ignored the question. Asked once again, he told the short Navajo to go away. A few more words were exchanged, this time in Navajo. Suddenly the small one jumped up and hit the tall one in the face. The tall one pushed the short one away and resumed leaning against the post. A few more words I couldn’t understand followed. The small one jumped up again and hit the tall one in the face. This time the tall Navajo pummeled the small one. The driver passed me the pint and asked, “How’d you like that?”

I was still sober enough to know that I was not going to get to the Grand Canyon anytime soon. I was torn between offending them and worrying about my safety. I told them that I thought I would spend the night at the hotel across the highway. “No rattlesnakes there, Michigan,” the driver said. I thanked them, grabbed my pack and headed across the highway.

As I crossed the highway, I saw a “No Vacancy” sign by the door. I walked in to make sure the sign was accurate. When the man behind the desk verified there were no rooms, I asked if I could sit in the lobby for a while. He agreed. I planned to wait until the pickup truck left and then start hitchhiking again. The pickup truck was still there 30 minutes later. I walked back across the highway, threw my pack in and climbed in the cab. I was passed the bottle. “We were waiting for you,” the driver said. He started the truck and we headed north.

The truck turned onto a dirt road 20 miles later. “This is where we go,” the driver said. “Come spend the weekend with us, Michigan.” I have often wondered if my life would have been different if I had accepted that offer. The Navajos are an interesting people and, over the years, I have visited their lands many times. Yet I have never again had an invitation to spend time with them. I thanked them and they drove off.

The Art of Hitchhiking

The more appropriate question that my Navajo guide could have asked was, “Does your mamma know that you are out here hitchhiking?” I haven’t hitchhiked in 30 years but there is no doubt that times have changed. In 1972, the freeway system was still under construction and this made hitchhiking easier. Two-lane highways are always easier for hitchhikers.

Looking back on the hitchhiking portion of my life, I often wonder if I was brave or crazy. Almost every ride was an opportunity of one sort or another. After all, who picks up a stranger along a highway? Sometimes bad things happen to the hitchhiker and sometimes to the driver. You read about those incidents. You seldom read about the good experiences that came from a long hitchhiking trip. My prime hitchhiking years were from 1969-1972. I didn’t own a car and reliable public transit seldom headed my way.

My Navajo experience was my most interesting experience. I found most people who stopped to give me a ride were true good Samaritans. They had hitchhiked earlier in their lives and were simply paying the courtesy they had received back. In Michigan, the cops stopped and brusquely checked my ID a few times. In Northern California, a California Highway Patrol officer went out of his way and gave me a ride into Reno. Of course, there were a couple of rides where the driver seemed a little bit sketchy but, hey, there is risk in everything we do in life.

I found that locals were a mixed bag. Hitchhiking to Lassen National Park, I got dropped off on the edge of Susanville. I had my thumb out in front of a house where a guy was working on a car. He looked up and said, “It’s a mighty hot day. Want a beer?” I accepted and we sat, drank a couple of beers and talked for a while. He wished me good luck. I returned to the road. The beer on an empty stomach had gone to my head.

A car filled with several teenagers came slowly by. The windows were down. “Asshole, you’d better get out of town,” was snarled by one of the passengers. “I’m trying,” I responded. The guy who had offered me the beer yelled, “You jerks, get outta here.” The car drove away. A few minutes later, I saw the car coming back. This time it was coming fast. I backed away from the edge of the pavement just in time to miss being hit by a flurry of thrown beer bottles. The buzz from the beers I drank probably kept me calm during the confrontation. Still, I was delighted when the next car picked me up.

Forty-eight years later, I still have a vivid memory of standing along US-395 with my thumb out. It was a beautiful day. The Sierra Nevada Mountains rose up above the road. The temperature was 70 degrees. I felt like I had the world by the tail. Remembering that day still brings a warm feeling to my heart. I was fortunate to have hitchhiked those many miles.

Something Grand

I quickly hitched another ride that took me to the junction for the road that led to the Grand Canyon’s east entrance. The sun was setting. I secured a motel room at the junction and slept off my drunkenness. The next morning, the first car (a convertible) driving by picked me up.

Although Grand Canyon National Park was less inundated by tourists in 1972 than it is in 2020, it was still crowded with tourists and cars. When I planned the trip, my goal was to hike from the Canyon’s South Rim to the North Rim. So I stood in line to get a permit and a map.

After a brief lecture by a Park Ranger, I made my way to the Bright Angel trailhead and started down into the abyss. The trail loses 4,460 feet in 7.8 miles from the rim to the Colorado River. The trail was crowded. All sorts of people from all over had the same goal. I was woefully over-prepared for the hike into a desert canyon. I had seriously upgraded my gear since my 1971 Montana trip. I had a new Trailwise backpack, the same one that Colin Fletcher (author of the ‘how to’ backpack book “The Complete Walker”) used. I had a Fairy down sleeping bag from New Zealand endorsed by Sir Edmund Hillary. I had a sleeping pad. I had a Bluet butane stove and an aluminum cook pot. I did not have any of the extraneous gear that I had lugged through Glacier National Park the previous year. All in all, my gear was tight.

I quickly learned that to hike across the Grand Canyon in August, I did not need the majority of the gear I was carrying. While I had packed properly for my upcoming assault on Mount Whitney, I had not thought out this part of the trip. As a through hiker with multiple destinations, I really had no choice. So instead of a 20-pound pack, I had a 40-pound pack. There was always someone to talk to on the descent. The walk was closer to a party atmosphere than a wilderness hike. Everyone was enjoying a sort of spiritual awakening as they descended. I paid little attention to ascending hikers stopped along the trail looking burned out.

Once at the bottom, I found a place to put down my sleeping bag at the campground at Phantom Ranch. It was hot. I joined other hikers soaking their tired feet in the creek. Good will and peace to all prevailed with this gathering. The campground ground was a utopian island. Getting down to the canyon bottom is one thing. Getting out is another. The North Kaibab Trail gains nearly 6,000 vertical feet in 14 miles. The Park Service warns hikers that the “North Kaibab Trail is the least visited but most difficult of the 3 maintained trails at Grand Canyon National Park.” Part of the difficulty is because the North Rim is 1,000 feet higher than the South Rim. Part of the difficulty for me was the beating that my body took carrying my heavy pack down the Bright Angel Trail the day before.

The next day I hopped up and promptly fell over. My feet were unbelievably sore. It was a while before I could put my weight on them. I decided to rest my feet and hang out for a day. Unique places like the Grand Canyon draw thousands of people who rush in, take a few photos and move on to the next destination on their checklist. Sitting in the bottom of the canyon that day, I had a few hours mostly to myself. The campground emptied as the campers headed off on their upward journey. The next day I started for the North Rim. My goal was to reach the Cottonwood Campground which was 7 miles away. I got an early start trying to beat the heat. It was a slow go. By the time I reached the Pumphouse Residence, the cool part of the day was over. I set up camp in a shady spot. The next day, I climbed the remaining distance out of the canyon.

California Here I Come

When I left Michigan, all that I knew about Mount Whitney was that (1) it was the highest point in the Contiguous 48 States, (2) that my road atlas showed a trail to the summit and (3) that it was in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, John Muir’s “Range of Light.” I actually had read a lot about the Sierra Nevada. In addition to Muir’s writings, Clarence King’s book “Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada” was and still is one of my all-time favorite tomes.

After reaching the top of the North Rim, I set my internal route finder for Lone Pine, California. I quickly got a ride with a man and his son who were heading for their home in Virgin, Utah. Virgin is located at the west entrance to Zion National Park. They dropped me off on the west side of town. Despite the fact that Virgin was a very small town and Zion was still an undiscovered masterpiece in 1972, I quickly got another ride. This ride was with a rancher who was heading to Saint George, Utah.

1972 was a Presidential election year. The Vietnam War was still dragging on. Richard Nixon was running against George McGovern. The World was in turmoil. Eleven Israeli athletes were killed at the Summer Olympics by Arab terrorists. B-52s were pounding North Vietnam. Alabama Governor and Democratic Presidential hopeful George Wallace was shot during a campaign event. America was divided between Nixon’s “silent majority” and those who were against the War and American Imperialism. In short, it was not a good time to discuss politics with strangers.

The first question from the rancher was, “Where are you going?” The second was “What do you think about McGovern?” I was hesitant to answer, not wanting to lose my ride. Before I could answer he said, “I hope he wins. We need a change before my son ends up dead in Vietnam.” The ride was great from that point on. We talked about everything from raising cattle in the desert (“a difficult enterprise”) to stories about the crazy tourists who stopped at his ranch looking for Butch Cassidy’s relatives.

I had the rancher drop me off at the Greyhound Bus Station in sleepy Saint George. Later that day I caught a Greyhound bus to Barstow, California. The bus left Saint George at around 10:00PM. I remember coming over a pass and observing a valley lit up like daytime—Las Vegas. Even in 1972, it was a fantasy land. I had to change buses in Vegas. It was around midnight and all around me were people playing slot machines, waiting for buses, smoking and eating–all oblivious to the late hour.

About 3:00AM, I arrived in Barstow. I got a $5 motel room near the bus station. It was undoubtedly the most primitive hotel I have ever visited. Having grown up watching black and white television shows and film noir classics which often included a scene or two in seedy California motels, it seemed appropriate that my first California night was in this motel.

I fell asleep for a few hours. When I awoke, I headed for the edge of town. My hitchhiking luck held. The second car picked me up. The driver was in the Navy and was stationed at nearby China Lake Naval Air Weapons Station. It was his day off and he was out to see the area. I told him where I was heading and he volunteered to take me clear to the trailhead. He also bought me lunch in Lone Pine and then drove me up to the Whitney Portal trailhead.

Mount Whitney

I remember looking at the Sierra Nevada Crest from the desert that surrounds Lone Pine. The mountains looked dry and hot from that perspective. I remembered the black and white Humphrey Bogart movie “High Sierra” which was shot at Whitney Portal. I also remembered Clarence King’s description of the range as he traveled south on horseback from Carson City to Mount Whitney:

“The Sierra, as we travelled southward, grew bolder and bolder, strong granite spurs plunging steeply down into the desert; above, the mountain sculpture grew grander and grander, until forms wild and rugged as the Alps stretched on in dense ranks as far as the eye could reach. More and more the granite came out in all its strength. Less and less soil covered the slopes: groves of pine became rarer, and sharp, rugged buttresses advanced boldly to the plain. Here and there a canon-gate between rough granite pyramids, and flanked by huge moraines, opened its savage gallery back among peaks. Even around the summits there was but little snow, and the streams which at short intervals flowed from the mountain foot, traversing the plains, were sunken far below their ordinary volume.”

When I arrived at Whitney Portal, the desert terrain had changed. A lush forest and beautiful granite surrounded me. I knew that I was in the right place. I found a spot in the Campground. My neighbors were all veteran Sierra campers and explorers. They offered good advice and information on the hike to Whitney’s summit. This was the first time on the trip where my equipment was perfectly matched to the terrain. At 8,300 feet, the Portal was the same elevation as the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. Yet I still had 6,000 feet to gain to reach the summit.

The Mount Whitney Trail climbs to the summit in 11 miles. I knew that the trail was going to be a strenuous hike and take me to elevations much higher than I had ever experienced. I had a topo map, a good description of the trail prepared by the Forest Service and enough knowledge to know that I would need time to adjust to higher elevations. I decided to take my time. After a night at the Portal, I hiked to the Lone Pine Lake junction. I was feeling the elevation and decided to spend an acclimatization night at Lone Pine Lake. Although the hike to the lake was only 3 miles, I felt good at reaching a new elevation record. This was my first time over 10,000 feet.

The next day, after a late start, I stopped for lunch at Outpost Camp. I was cooking Lipton Soup for lunch when I was accosted by 2 hikers who wanted to know if “in all my world travels I had found the Lord?” I could not shake them as they were intent on proselytizing. As I swallowed my soup, one started reading from his Bible. I packed up quickly and started up the trail. As I recall, I Ieft them to ponder a few choice (expletive deleted) phrases relating to solitude and Jesus’ 40 days in the desert. As I looked back down on Outpost Camp, the 2 missionaries were now continuing their high altitude ministry with another unsuspecting hiker who had just fallen into their clutches.

The trail now climbed relentlessly toward my goal for the day–Trail Camp. The terrain was now treeless with vast expanses of polished granite, talus fields, meadows and sparkling water. Each step was a new altitude record. I reached Trail Camp at just over 12,000 feet by mid-afternoon. Trail Camp was a meadow with small ponds. I found a flat, sandy spot next to a granite wall and set up camp. Around 5:00PM, a small troop of Boy Scouts arrived along with their Scout Master. They dropped their packs and rolled out their sleeping bags around my spot. Given the number of people at Trail Camp, people were crowded together in every flat space. So much for solitude.

Later that evening, I was talking to the Scout Master. He questioned me about my experience. He was dumbfounded that I was hiking Mount Whitney by myself. He told me how unsafe it was to hike alone. Looking around us at the nearly 50 people in view, I told him, “If this is hiking alone, I doubt it is that dangerous.” The night was the coldest I had yet experienced. I pulled the hood on my sleeping bag tight and stared at the star display until I dozed off. When I awoke, frost covered the meadow grass and ice topped the still water. It took me awhile to find the courage to unzip the sleeping bag. I certainly was not going to make an alpine start.

From Trail Camp the trail climbs up to the Sierra crest at a point known as Trail Crest in just over 2 miles by using 97 switchbacks. I put on every top I had, two T-shirts, a wool shirt, a nylon sweater and a 60/40 parka and started up the trail. I progressed one switchback segment at a time. The trail soon reached a sunny slope and I warmed up. Reaching Trail Crest at 13,645 feet opened my mind to why John Muir called the High Sierra “The Range of Light.” The massive view was a revelation of what could be. Between my perch and the distant Kaweah and Great Western Divides was the massive Kern River drainage. Miles and miles of high country cut by the deep Kern River Canyon. Big peaks reached to the sky in every direction. I was getting a heavy dose of vitamin D and I was pumped.

From Trail Crest, there was still another 2-1/2 miles to the summit. As I rested, a kid came walking down the narrow trail. He was weaving and looked a bit worse for the experience. “Did you make it?” I asked. “What?” he responded before he spotted me. “I’m so dizzy,” he said as he continued down the trail without another word. A slight breeze was chilling me as I started following the trail toward the summit along Whitney’s needle-encrusted South Ridge. Once I started up the summit plateau, I reached a spot where the trail forms a trench through large talus field. I sat down to get out of the wind for a minute.

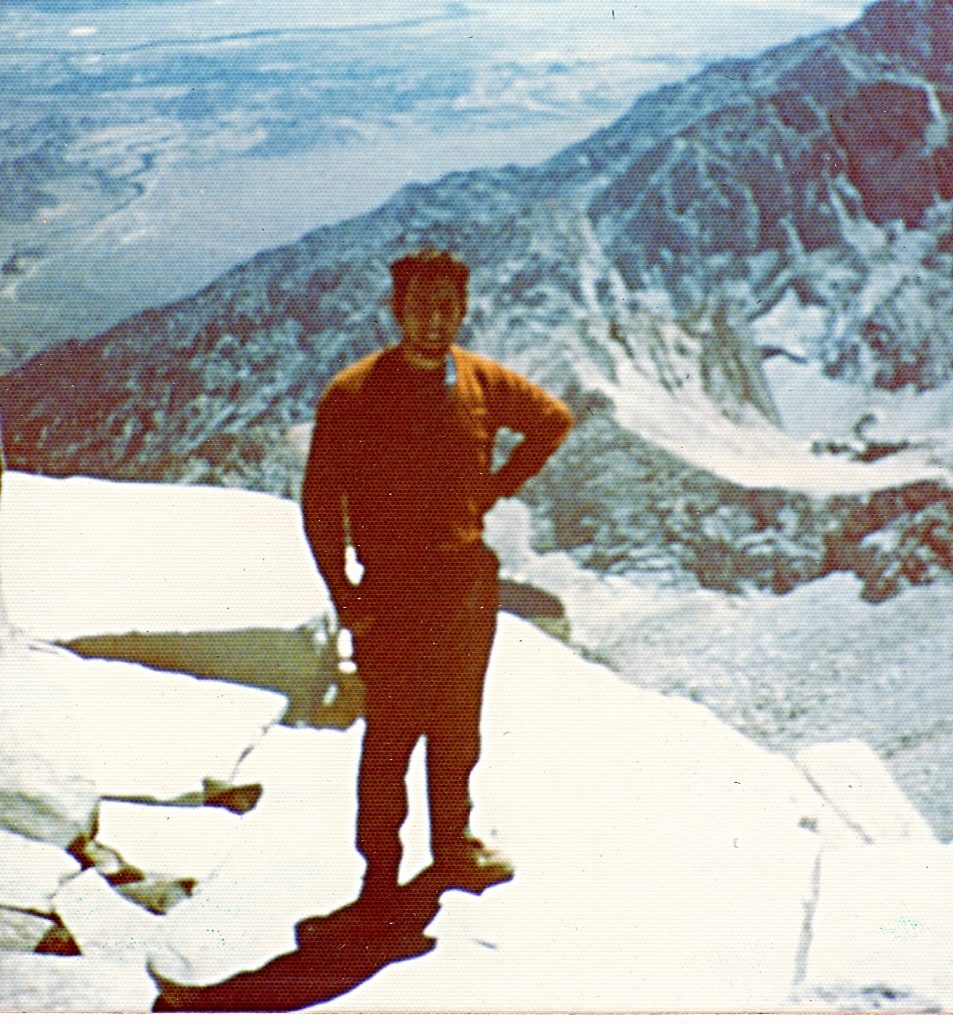

The next thing I knew, 2 hikers were shaking me. “Are you okay?” one asked. “We thought you were dead,” the other said. I had fallen asleep in the middle of the trail. A bit embarrassed, I thanked them and continue on to the summit. The trail ends at a stone cabin on the massive summit of Mount Whitney. My first Western mountain was climbed. I felt the same way on that day that I feel today when I reach a mountain top—so many mountains to climb, so little time.

Lassen and the Naked Ones

After Mount Whitney, I decided to head north to Lassen Volcanic National Park. My luck with rides continued and I managed to reach Lassen in 2 days. I did have to walk most of the way across Reno but back then it was not yet a sprawled-out metropolis. I picked up a hiking permit at the visitor center as well as a ride to the trailhead. The ensuing backpacking trip was only notable for all of the people skinny-dipping in every lake I passed. After 2 nights, I decided that hiking alone in a crowd was actually lonely. It was time to head to Idaho.

Great Aunt Ethel and Paul

My mother was orphaned at an early age. Her father died from sepsis in an age before antibiotics. Her mother died from an automobile accident in a time before seat belts. Her life after these losses was in a way—Dickensian. She was passed around between relatives. The most notable period was when she lived with a strict Methodist minister and his wife. Meanwhile, her younger sister was adopted by one of the richest families in Logan, Ohio. One of the shining lights in this dreary portion of her life was her mother’s sister Ethel, my Great Aunt Ethel.

Some of my earliest memories are Christmas cards that we received from Ethel. She had long ago married and left Ohio for the wilds of Idaho. The letters that accompanied her Christmas cards told tales of the Wild West, of earthquakes and bears, of cabins in the mountains and floods in the valleys. When my mom wrote to Ethel about my 1971 trip to Montana, Ethel immediately wrote back demanding that if I ever returned to the West that I stop and visit her in Idaho Falls.

Tired of hitchhiking, I bought a train ticket from Reno, Nevada to Ogden, Utah. The train dropped me at the Ogden train station early in the morning. I fell asleep on a hard bench. I was awakened by an employee who said that the cops would arrest me if they found me sleeping in the station. I asked him where the bus station was located. I stumbled around town for an hour or so until the bus station opened, bought a ticket to Idaho Falls and fell asleep again.

The bus ride to Idaho was uneventful. I sat with a young Mormon woman who told me about her faith and a bit about the country were were passing through. Arriving at Idaho Falls, I called Great Aunt Ethel’s number. She answered. “Don’t move. I’ll be right there,” she said. True to her word, she arrived 15 minutes later. She was a woman who I never met and whom my mother had not seen on over 30 years. None of that mattered. We were family. For the first time in my journey, I had nothing to worry about. Ethel’s husband Paul Masters came home from work around 6:00PM. I did not know it at the time, but Paul would play a big part in my life for the next 15 years. After Ethel introduced me, Paul’s first question was “Lopez, what kind of name is that?”

Paul’s vacation was starting 2 days later. The plan was to spend 2 weeks at their cabin above Palisades Reservoir. I was invited. We were joined by Ethel and Paul’s daughter Judy and her husband Guy. Paul was a self-taught jack-of-all trades. He had designed the cabin and done all of the finishing work. Everything fit together with engineering precision. The cabin sat on a bluff several hundred feet above the reservoir. In years to come, I would be fortunate to spend many days at the cabin.

The next week was full of good times–from boating on the reservoir to visiting Jackson Hole to hiking above the cabin. Each day was a joy capped off by cocktail hour which started promptly at 5:00PM. Their Western lifestyle was so different from anything I had experienced. Paul was a firm believer that if you wanted to stay young, you do the things young people do. So we listened to Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, had riveting discussions and seldom sat still for anything other than meals and cocktail hour.

Doug Again

The letter from Doug that I mentioned at the start of this reminiscence gave me a specific date, time and place to meet up with him. I had mixed feelings. I wanted to take a backpacking trip. I also thought it stupid to leave my aunt’s company. I decided to opt for a potential backpacking trip. I forgot my mom’s admonition that “a bird in the hand is worth many in the bush.” I also chose to forget my numerous experiences with Doug’s ever-changing priorities. So on a Saturday afternoon, Paul, Ethel, Judy and Guy took me to the University of Michigan Geology Camp to meet up with Doug at the appointed hour. Of course, Doug wasn’t there. I was told he would be back. My entourage refused to leave me until Doug arrived. So we sat there uncomfortably for 3 hours. Doug finally arrived in a beat-up 1950s-era pickup truck. As in 1971, he acted surprised to see me.

Yellowstone to Bozeman

The next day we headed north. In keeping with Doug’s aversion to paying entry fees, we couldn’t go through Yellowstone National Park. Instead, we crossed over Teton Pass and then drove backroads up to West Yellowstone. We camped near Quake Lake. In the morning, we got up at first light so that we could drive into the Park before the entrance station opened. We did not have a plan but we had thought vaguely about a backpacking trip. Every time I brought that possibility up, Doug would change the subject. After hanging out in the geysers basin around Old Faithful, Doug said “Hey, there is a party tonight in Bozeman. Let’s go.”

“I thought we were here to hike,” I responded. Doug didn’t respond at first but then agreed to go on an overnight backpack. I suggested a backcountry lake that I found on the map. We started to drive toward the the Park’s northeast entrance. There was absolutely no traffic. Doug was now telling me about his concern that we would run into grizzlies if we hiked to the lake I suggested. The road crossed a large meadow. Ahead of us, we saw rain falling. Doug slowed and then stopped. Rain was falling on the truck’s hood. It came down in a straight line. The rest of the truck was dry. There was no wind. It was a another surreal experience. The line of rain moved off the hood and up the road.

Doug finally said, “We need to find a different place to backpack.” He turned the pickup truck around and we drove back to West Yellowstone. We arrived in West Yellowstone around 6:00PM and ate a burger. I suggested that we camp again by Quake Lake but I knew nothing that I said was going to deter Doug from driving to Bozeman for the party. His pickup truck ran well but its rear running lights and brake lights did not work. Darkness fell as we drove toward Bozeman.

Vehicles would come up fast behind the nearly-invisible pickup truck, see us at the last minute, slam on their brakes and then pass us. No one hit us. We reached Bozeman at around 10:00PM. Doug drove around for an hour before he found the address that he was looking for. He parked. “Come on,” he said, “it will be fun.” I declined. I was pissed. I could have stayed with Ethel and Paul. Lessons are better learned later than never. After an hour, I put on my backpack and walk to Bozeman’s main street. I got a room at the old Bozeman Hotel. The next day, I caught the train east. Another Summer adventure was over.

NEXT: The Middle of Nowhere, Idaho, 1972